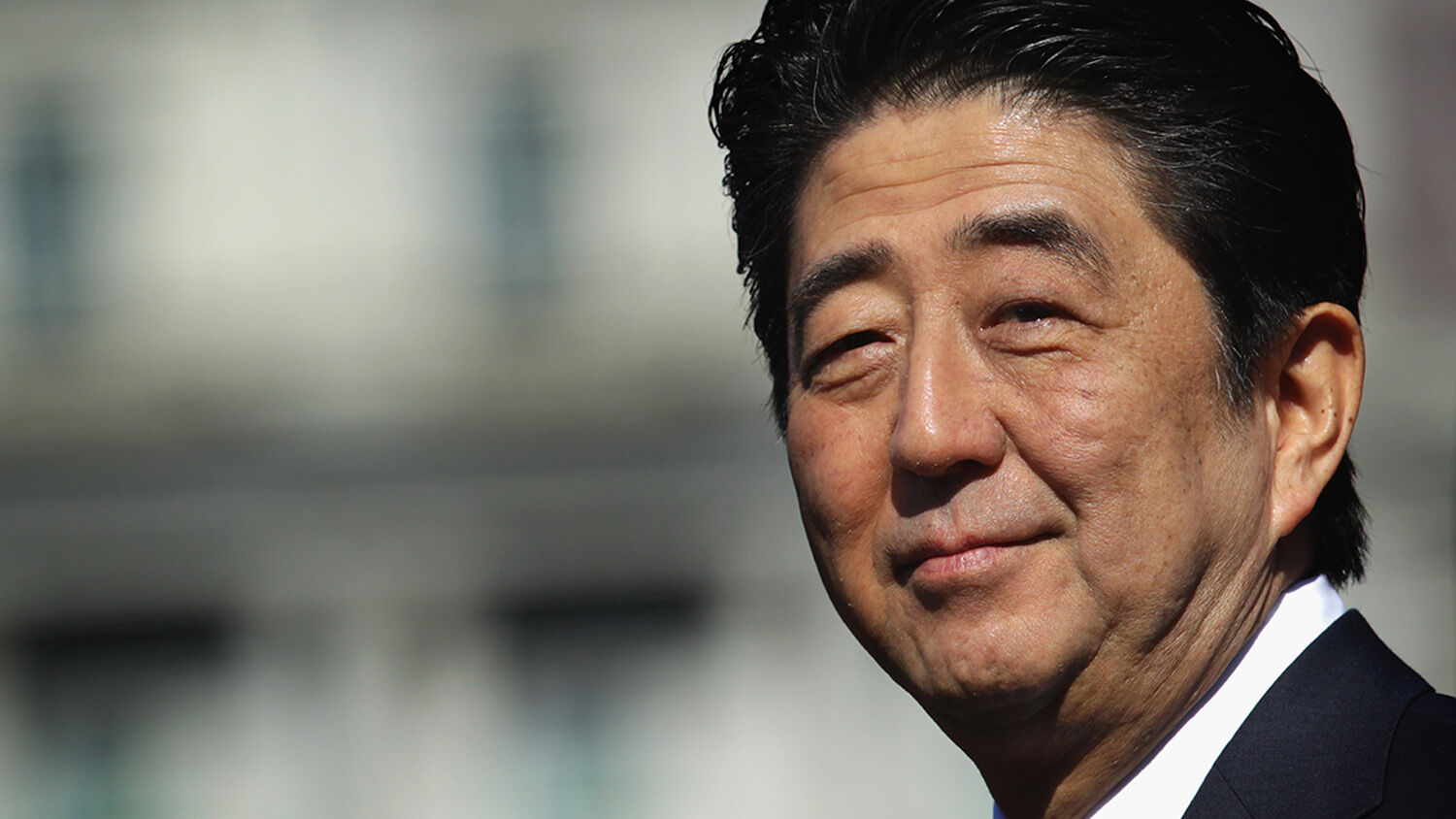

Japan Opens Door to Third Term for Prime Minister Shinzō Abe

The stability that Prime Minister Shinzō Abe has given Japan is an anomaly in the past three decades of instability. For that reason, Abe’s ruling party is eager to keep him in office. Consequently, on Sunday, the party announced it would extend the term limits for its leaders, meaning Prime Minister Abe may become Japan’s longest-serving postwar leader.

This move is not a behind-closed-doors totalitarian takeover of the Japanese government that you might suspect if you saw the same event occur in an African dictatorship. It involves no change of Japanese law, merely a change in party policy. According to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s (ldp) previous policies, Prime Minister Abe would have to step down as leader of the party after two three-year terms. The policy was introduced in 1980, when Prime Minister Eisaku Sato’s eight-year service from 1964 to 1972 was criticized for concentrating too much power in one man. The ldp has simply to make an internal decision, well within its power, to extend that limit to three terms—or nine years.

However, as a Japan Times editorial pointed out, “given the ldp’s long hold on power, its rules on presidential terms effectively determine the tenure of the prime minister.” Since 1955, the ldp has dominated politics so thoroughly that it has only given up leadership of the nation twice in 62 years. The Japan Times, writing while the party discussed the change last September, continued:

Party elders involved in the discussions deny that they’re merely seeking to keep Abe at the helm. … One point about the ldp presidency rules should be sorted out. When Abe was reelected party chief a year ago, the rule at that point dictated that the new three-year term he was given was going to be his last. It must have been the understanding of ldp lawmakers who either supported his reelection or who gave up challenging him that he would not be running again in 2018. Altering this regulation now—and making it applicable to Abe—smacks of changing the rules in the middle of the game.

A note for the Western reader. The name Liberal Democratic Party might give one the impression Abe’s party leans left. Not so. (Our article “The Cryptic Nationalist Group Steering Japan” from the March Trumpet magazine explains the party’s roots.) One of the ldp’s three factions is the nationalist Japan Democratic Party. Its minister of defense (among many others), Tomomi Inada, visits the Yasukuni Shrine: a war memorial which, when visited, causes outrage from the surrounding Asian nations because of the number of war criminals enshrined there.

Abe’s party has been the driving force behind recent changes in the interpretation of the Japanese Constitution. Although Japan is considered a “pacifist” nation because of Article 9 in its Constitution, which “forever renounce[s] war as a sovereign right,” it now has troops stationed in South Sudan. Prime Minister Abe is the most powerful supporter of further changes to the Constitution. There are dissenters within the party of course, but on a whole, the ldp adopts a policy principle of “taking a practical step towards proposing amendments to the Constitution.”

As the term-limit extension was announced, Agence France-Presse reported Abe asking: “The ldp will lead concrete discussion towards proposing amendments to the Constitution. This is the ldp’s historic role, isn’t it?”

In effect, the term-limit extension will give Abe the chance to push ahead with the ldp’s “historical role”—that is, lifting Japan from pacifism and re-creating the nation as a proactive military power.

If Abe runs for another term and is successful, he could be prime minister until 2021. No one can tell whether he will last that long or whether he will be able to push forward with his constitutional changes. Scandals surrounding his wife, Akie, have been growing, and there’s no telling whether they will catch hold. Nevertheless, Abe’s popularity is still at 60 percent levels, and the party trusts that he is the one to lead the transition nation. The extra three years would give Japan’s “constitutional scholars” time to reinterpret some more clauses, and the ldp time to normalize and extend the use of Japan’s (fictional) “Self-Defense” Force. Maybe Shinzo Abe will be the man to finally push through historic changes on Article 9. Maybe it will be someone else. What is sure, is that Japan’s ultra-dominant party, the ldp, is in line with Abe’s vision.

The above-mentioned article from the March Trumpet quoted Herbert W. Armstrong’s forecast that “Japan would awake from its postwar slumber, cast off the pacifism the U.S. imposed on it, and return to formidable militarism” (Plain Truth, March 1971). Mr. Armstrong continued:

Japan today has no military establishment. But we should not lose sight of the fact that Japan has become so powerful economically that it could build a military force of very great power very rapidly.

“Fearmongering!” no doubt, was the accusation of many when they read that in 1971. It’s no longer far-fetched. Many Japanese politicians are putting forward the same proposals themselves. Whether Prime Minister Abe will be the one to make a militaristic Japan a reality is still to be seen. But the term-limit extension will give him a few more years to make it happen. Readers of the Trumpet will do well to continue watching Japan’s transition. If you don’t know why the Trumpet watches this trend, read “Why the Trumpet Monitors Japan’s March Away From Pacifism and Toward Militarism.”