Power-Sharing Deal Reached in Zimbabwe

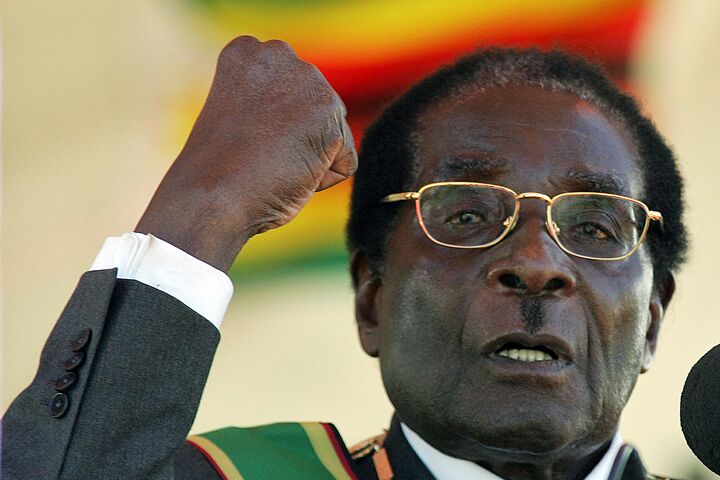

Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai reached a power-sharing agreement September 11, which was signed this Monday. Despite hopes for a new democratic era in Zimbabwe, however, Mugabe will retain much of his power, against the will of the people.

The power-sharing deal follows months of political turmoil and violence following March elections in which Tsvangirai, leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (mdc), gained the most votes. Mugabe, head of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (zanu-pf) and dictator of Zimbabwe for nearly three decades, refused to recognize the results, embarking on renewed violent intimidation of opposition politicians, their families and voters, and conducting a second-round poll in June. Tsvangirai boycotted the vote because of the violence against his supporters.

Under the power-sharing arrangement, Mugabe will stay on as president and retain control of the all-important army and intelligence services. Tsvangirai will be given the newly created post of prime minister—and with it, the country’s enormous problems. The new cabinet will slightly favor the two opposition parties, though Mugabe will retain overall control of it. Talks to form the new cabinet, originally scheduled for Tuesday, are now slated to be held today.

The deal, says Stratfor (September 12),

is more image management than a substantial shift in executive power from President Robert Mugabe to opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai. [T]he deal will not substantially alter Mugabe’s grip on power due to his expected continued control over the most significant cabinet positions and ministries. …

Ultimately, given Mugabe’s control over the armed forces and a capable private militia (not to mention veto power in the country’s Senate over any untoward mdc moves in Zimbabwe’s lower house of assembly), his government will be able to contain Tsvangirai’s from several angles.

South African President Thabo Mbeki has been given credit for mediating the power-sharing deal, though, as the Christian Science Monitorcomments, “one wonders what might have emerged had he handled Zimbabwe’s dictator with anything rougher than kid gloves.”

Mugabe clearly only agreed to share power with his opposition because the deal was in his favor and—he hopes—will end Western sanctions on the country, which has been economically destroyed over the past decade. Ultimately, Mugabe’s prime motivation in acquiescing to the deal was simply self-preservation.

Mugabe’s ruinous rule of his once prosperous country has destroyed it. As Roger Bate at the National Review Online describes (September 15),

The suffering in Zimbabwe is tragic, millions have fled the country and thousands die weekly, defenseless against common diseases due to malnourishment. Most food aid is still unavailable to those in areas which have supported the opposition mdc. Property theft, reckless monetary policies, and total disregard for the rule of law have brought the economy to its knees. zanu pf imposed price controls but this failed to dampen inflation and drove trading to the black market. Inflation still surges—officially annualized at over 11 million percent, though perhaps much higher say independent observers like local economist John Robertson—and has become so bad that the government resorted to dropping 13 zeros from its currency last month in order to allow atm machines and calculators to handle basic transactions.

In the face of such economic humiliation, Mugabe relented to the power-sharing deal with his opposition. “[I]f the international community is pleased enough with the power-sharing agreement to come to Zimbabwe’s rescue with aid packages,” writes Bate, “it is doubtful that mdc will ever truly take power: Once the economy is back on its feet, the generals—with or without Mugabe—will reassert total control” (ibid.).

The tragic failure of democracy in Africa isn’t limited to Zimbabwe of course. Strongman rule has brought suffering and economic ruin to many African states. It is the way of the plundering dictator, the “Big Man,” that has dragged nearly all of Africa into rank poverty, economic and social collapse. As an experiment in democracy, Africa has failed abysmally. In the post-colonial generation between 1957 to 1990, “Not one African head of state, even in nations that tolerate a measure of democracy, has permitted voters to end his reign” (Blaine Harden, Africa: Dispatches From a Fragile Continent).

For more on the failure of democracy in Africa and how the continent’s woes will end, read “The Failure of African Democracy,” “Kenya Exposes Democracy’s Flaw” and “The Big Men.”