The Miracle at Midway

June 4, 1942. The South Pacific Ocean is on its way to becoming a Japanese lake. Since their first smashing surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Navy and Air Fleet have strung together an almost perfectly unbroken chain of Japanese victories and American humiliations. Now the empire of the rising sun has its sights set on a new target: Midway.

American morale is sitting low in the water, and Japanese confidence couldn’t be flying higher. Dec. 7, 1941, a day which still lives in infamy, had brought an astonishing Imperial Air Fleet morning attack that obliterated the notional state of peace that existed—as well as American deterrence and military pride. Japanese pilots sank or almost ruined 350 aircraft and 18 ships, including all eight battleships of the United States Pacific Fleet. Almost 2,400 servicemen were killed. Japanese losses for the day totaled less than 70 men and only 29 of its 353 planes.

“WAR!” Daily newspapers proclaimed the news from the theater—and the news was bad. Since the Pearl Harbor pummeling, every battle further torpedoed American power in the Pacific. The Japanese Empire advanced through Guam, Wake Island, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore and Burma—brutally.

Today, it is Midway’s turn.

Japan’s First Air Fleet plowed eastward through the swells at 16 knots, a sailing steel citadel bristling with firepower and multiple victories in a war less than six months old. There were 11 destroyers; a pair of ironclad heavy cruisers; two gigantic 30,000-ton battleships; and the carriers that blasted Pearl Harbor: the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu.

That wasn’t all. Another strike force steamed for Dutch Harbor, in the Alaskan Aleutian Islands, for a diversionary attack to draw American ships away from the real battle. But that wasn’t all. A third squadron of warships was positioning itself between the Aleutians and Midway to provide reinforcements when and where needed. But that wasn’t all.

A few hundred miles behind the carriers of the First Air Fleet, the main body of the Japanese battle group cut through the waves, starring the deadliest, most gigantic battleship in the world: the Yamato. When anyone dared to nose out of port to help Midway, the enormous assortment of battleships, destroyers, cruisers and light carriers would send them to the bottom.

The Japanese warriors knew how to win, and they were used to it.

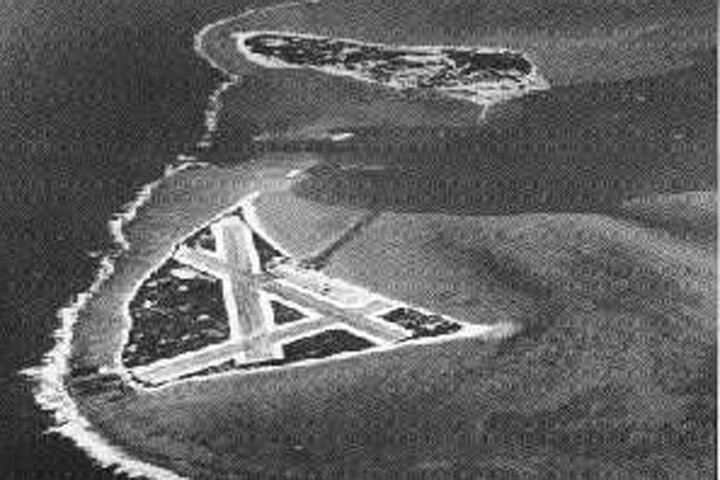

And tiny Midway was next. It was a truly miniscule coral atoll more than a thousand miles west of the nearest inhabited Hawaiian island—basically two spits of sand with a runway. Once the Japanese conquered Midway, they would control a strategic position roughly halfway between Tokyo and San Francisco, enabling the empire to launch offensive actions throughout the Pacific. Eventually, they could conceivably strike the American West Coast, putting the war right into American cities and homes—literally inside their living rooms, and not just on television. More immediately, the Japanese were determined to sink the Navy’s remaining carriers and finish off what was left of its morale.

But one thing was working for the outgunned and outnumbered Americans. They knew the Japanese were coming.

Of all the destruction the Japanese wreaked at Pearl Harbor, they missed the code crackers’ facility. And American cryptographers there had discovered that something big was about to rain down on Midway. So its defenders dug in.

An unseen hand had also given the Americans another fighting chance. The early World War ii U.S. Navy was designed to function similar to the way navies had fought for centuries: Put your biggest guns on your baddest battleships and get them in the water. Cruisers, destroyers, submarines and carriers served more of a supporting role. But on Dec. 7, 1941, Japan bombed Battleship Row to pieces. American strategists could no longer rely on the weapons they had built the entire Navy around. They were forced to turn to the next best thing: the aircraft carrier. Yet unbeknownst at the time, it would actually be the carriers—not the battleships—that would rule the seas for the next 70 years … starting now.

Confronted with the situation, Adm. Chester Nimitz made a bold move and decided not to devote resources to bringing in additional battleships from the West Coast and instead to put all his emphasis on his three carriers. He had little choice.

On June 4, at 0400, Japanese bombers and fighters fired their engines and shot off their carriers. A couple hours later, air raid sirens on Midway began wailing, and men rushed to battle stations. The atoll’s small complement of combat planes roared into the air. They were antique, slow-moving Brewster Buffalo fighters, also known as “Flying Coffins.” They were massacred.

Then Midway disappeared under the bombs. Fuel tanks, gun emplacements, ammunition dumps, fuel lines, buildings, the powerhouse—exploded. Smoking planes plunged back down in blazes of orange flames and black smoke. One pilot bailed out, but enemy planes continued to gun him down as he dangled from his parachute, even when he landed on the coral reef below.

But Midway’s bombers had already taken off. Now they vectored in on one of their attackers: the Akagi carrier, flagship of the Japanese fleet. The Akagi’s fighters, including the amazing Mitsubishi Zero, cut them to pieces. One damaged B-26 struggled to continue its bombing run and hurtled straight at the ship’s bridge. It missed by mere yards, crashing into the waves. The Akagi’s sailors literally jump for joy. One officer exclaims, “This is fun!”

There was still hope though. Midway’s Dauntless dive bombers had found the Hiryu carrier. They plunged into their attack, their flat-top target disappearing in an explosive haze of smoke and waterspouts. Looking on, the Akagi crew feared the worst. But Hiryu sailed majestically out of the chaos—having wiped out half of the American planes.

Later, 14 of Midway’s B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers appeared above the carriers, free from harassment by the Zeros and with a clear shot at the carriers. They missed everything. Japanese contempt for American naval aviation seemed to be well-earned.

But now the American carriers arrived: the Hornet, the Enterprise and the Yorktown. The Japanese had damaged the Yorktown so badly 27 days prior that they thought it was at the bottom of the ocean. But instead, the Yorktown had limped back to Pearl Harbor for what should have been more than 100 days of repairs. They did the best they could in 72 hours and put it back to sea—with repair crews still inside, still fixing it. Desperate times called for desperate measures.

These three carriers had thus far eluded the Imperial Navy’s search attempts. They were the last hope for the Battle of Midway.

One torpedo plane squadron from the Hornet intuitively headed for what was actually the enemy carriers’ new position, but Zeros zoomed up and destroyed all 15 American planes. Another 14 planes from the Enterprise arrived, but their torpedoes missed the mark. The Yorktown’s planes were also massacred. Out of 41 total American torpedo bombers launched, only four would survive the day. Zeroes blasted away and plane after plane crashed into the sea to the cheers of Japanese sailors and pilots on the flight deck who by now felt invincible.

“We don’t need to be afraid of enemy planes no matter how many there are!” one crewman exulted.

But the pilots of these outdated, outmatched, outlived planes did not die in vain.

As the torpedo bombers live out their minutes-long life expectancies, 33 Enterprise dive bombers drone along over the empty blue space where the Japanese were supposed to be, dozens of miles away. With fuel running dangerously low, Lt. Cmdr. Clarence W. McClusky Jr. has to decide whether to patrol this area until the Japanese show up—if they ever do—or to begin an expanding-box search pattern until his fuel runs out. He does neither. Instead, he flies west an extra 35 miles, then banks northwest. His planes likely won’t have enough fuel to get back, they still don’t know where the Japanese are, and they might all run out of gas and crash into the ocean without ever firing a shot.

It’s an unconventional and possibly foolhardy decision. Or possibly the providence of an unseen hand. Adm. Chester Nimitz would call this “the most important decision of the battle.”

Then, in the deep blue depths below, McClusky spots a white wake. It’s an Imperial destroyer. Intuitively, he decides it must be a straggler, and follows it. Minutes tick by. Some planes have to ditch because of low fuel. Two minutes, five, ten ….

Then, it’s there. White wakes from Japanese destroyers, cruisers and three carriers.

They’ve found the Japanese fleet. Not only that, but McClusky’s dive bombers are blessed with intermittent cloud cover. Not only that, but the Japanese flight decks are filled with planes, explosive ordnance and fuel lines. Not only that, but all the Zeros are currently busy, chopping apart torpedo bombers down around sea level around the Hiryu, which is well to the north of its three sisters. Not only that, but 17 dive bombers from the Yorktown happen to arrive at that same perfect spot within seconds, by sheer chance—or an unseen hand.

Now America’s own mistakes and misfortunes begin to work for it. The next few short minutes would change the battle for the Pacific.

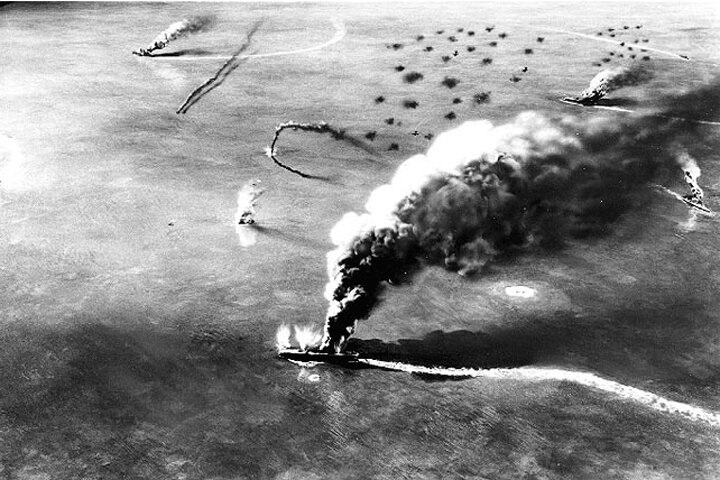

From 20,000 feet, America finally struck back. Yorktown bombers dive toward Soryu. McClusky and the squadron from Enterprise hit Kaga. The first three miss. The fourth explodes among the takeoff-ready planes on the flight deck. More bombs find their mark, one hitting the bridge, and the Kaga is ablaze. In just three minutes, Soryu gets hit three times. Fires erupt and set off explosions that start more fires, spreading through the ship. Akagi scrambles its fighters. Only three American planes dive at it—and one misses. But one hits. The other hits the midship elevator, its bomb exploding among the planes below decks. Normally, two hits would not doom a carrier, but the Akagi and its sisters are caught with their decks and hangars full of warplanes and explosive ordnance, much of it not stored away but stacked in the open due to the rush.

On the Hiryu, 100 miles away, Rear Adm. Tamon Yamaguchi hears the shocking reports and decides the Hiryu will just kill the whole enemy force by itself if it has to. And he makes a good start of it. The Hiryu launches an attack wave of dive bombers, which strike the Yorktown 40 minutes later. A bomb pierces the flight deck near the number-two elevator and starts a fire in the hangar deck below. A second bomb goes through the Yorktown’s stack and into the boilers, snuffing them out. A third bomb pierces the other elevator and detonates near the ship’s fore gasoline storage. Stricken and burning, the carrier struggles along, then stops dead in the water as its repair crews try to patch it up. Again, the Japanese believe it is sunk.

By either chance or intellect—or an unseen hand—Spruance resists calls by his officers to retaliate immediately. Aboard the Enterprise, he insists on waiting for reports from the scout planes. He wants to see if the Hiryu has changed position. If he launches planes now, the target might not be there.

And it isn’t.

The Hiryu had launched its first wave, turned north, launched a second attack, then turned northeast. An American retaliation might well have missed the Hiryu altogether.

Now, the second Japanese strike wave finds a carrier, which they presume to be the Enterprise. It’s actually the Yorktown, which is underway again. Two torpedoes miss their mark. But two others hit home and finally knock it out of commission.

Meanwhile, a scout plane from the Yorktown radios in that it has found the Hiryu. Spruance launches his remaining 24 bombers.

Hiryu is now preparing for a third successful strike. Suddenly, American dive bombers come screaming down out of the wild blue yonder. Four hits, all at once. Fires erupt, spreading throughout the ship. Before long, Hiryu too is astonishingly burning from bow to stern. Just like that, Japan’s First Air Fleet has lost all four of its mighty carriers.

Soon after, the Battle of Midway was over. Four of Japan’s proudest and most important ships, an accompanying warship, 248 of its aircraft and more than 3,000 of its men, its indestructible morale and its dream of an unbounded empire were lost. After eventually losing the Yorktown, a destroyer, about 150 planes and 307 men, America still had a long fight ahead, but Midway would prove to be the turning point of World War ii in the Pacific.

Midway is just one entry on a long roll call of miraculous events that have preserved the independence and power and blessings of the United States of America—all guided by an unseen hand.

As we go about our lives this June 4th, let’s remember what others were doing on this same day, exactly 70 years ago. Remember the history, remember the heroism, remember the “luck.” Remember why we still call it “the miracle at Midway.”