The New U.S. Dietary Guidelines Are Good. Now What?

The New U.S. Dietary Guidelines Are Good. Now What?

For the first time in decades, the United States federal government dietary guidelines point out the primary driver of our chronic diseases: added sugars and ultra-processed foods.

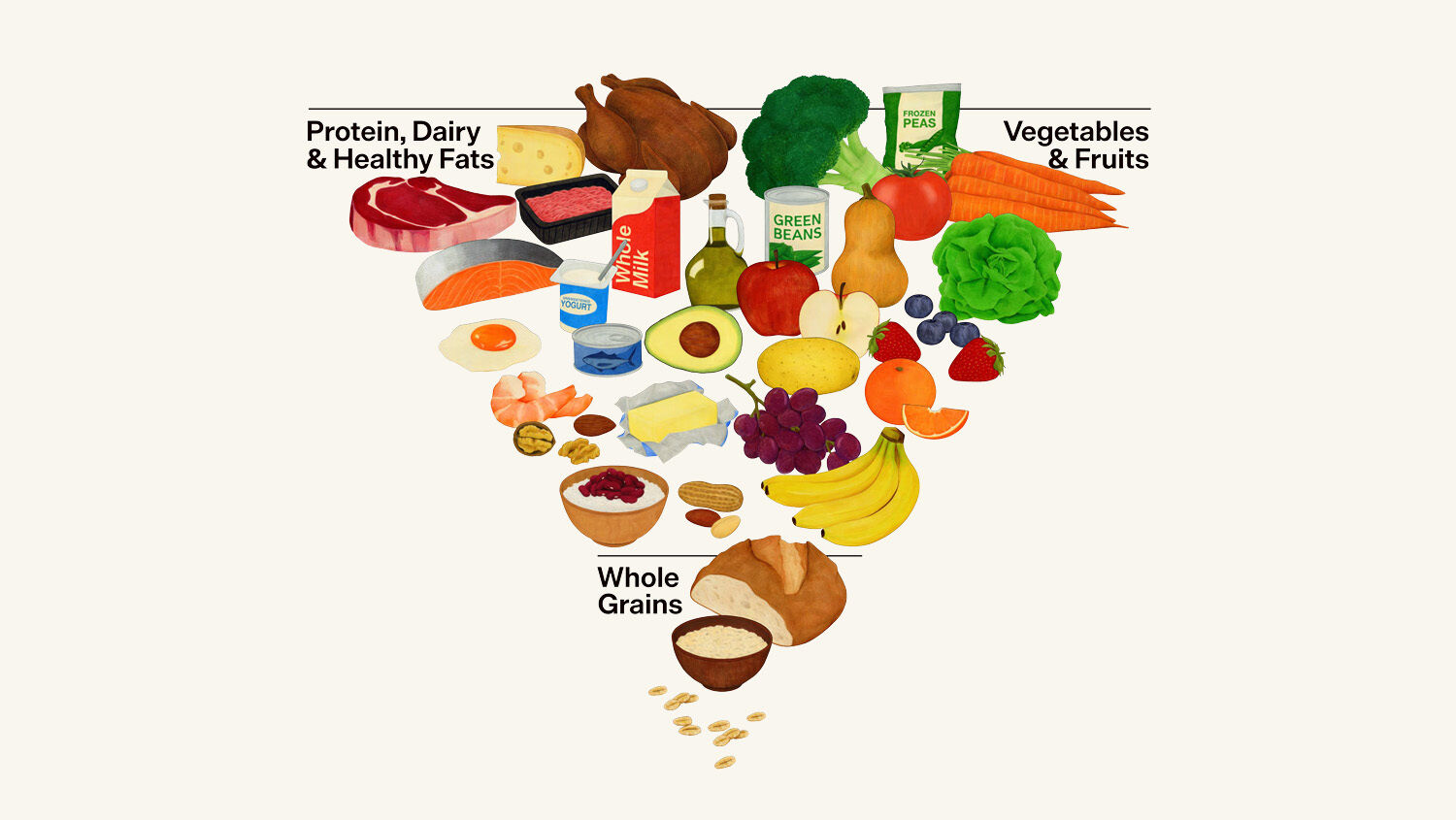

The new guidelines were released January 7 by the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Agriculture. In them, protein receives a major upgrade, with guidance to prioritize it at every meal. Full-fat dairy is now permitted when it contains no added sugars, and the fear-inducing language against whole-food fats is noticeably toned down. Previous limits on saturated fats remain. The guidance on added sugars is self-contradictory, but the 2025–2030 guidelines are a dramatic improvement, flipping previous approaches, promoting real foods and—for the first time—explicitly stating that ultra-processed products should be sharply limited. Just as importantly, they steer people away from refined grains, excess sugar and industrial fats; expand guidance across different stages of life and health; and deliver the message in a way that is far easier for consumers to understand and use.

Remarkably, this reverses long-standing nutrition logic. The old system tried to manage nutrients inside an industrial food environment. The new system finally recognizes the environment itself as the problem. This is the closest that federal nutritional guidance has come to metabolic reality in decades.

Ultra-processed foods drive obesity and chronic disease, not because of one nutrient but because industrial formulations disrupt appetite regulation, insulin signaling, gut signaling, satiety hormones and reward pathways at the same time.

Higher intake of these foods is associated with increased exposure to chemical residues such as phthalates and bisphenols. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences has shown that when multiple chemicals are present together, their combined biological effects can be very different, and often more harmful, than each chemical on its own.

The new guidelines finally tackle the issue of ultra-processed foods because the massive institutional framework for creating, promoting and consuming these products is still very powerful.

Independent analyses of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee itself still show extensive conflicts of interest. A systematic analysis in Public Health Nutrition found 95 percent of 2020 committee members had food industry or pharmaceutical industry conflicts.

The Nutrition Coalition says many committee members had ties to major food and health companies, but the way the government reported those ties made it difficult for the public to see exactly who was connected to which companies. The Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services have also disclosed conflicts of interest in ways that make independent review difficult, the Center for Science in the Public Interest has said.

While these ties don’t mean the new advice is wrong, they do affect the conversation. The focus stays on education and “personal choice,” while enforceable or even strongly recommended measures like restricting junk-food marketing, changing farm subsidies, or protecting children from aggressive advertising, remain limited or largely absent from the final policy. That is disappointing. Though this administration clearly understands the scale of the problem, the final policy still avoids recommending the bold structural changes that would most effectively confront it.

The guidelines are the legal backbone of federal nutrition policy, shaping food purchasing and preparation for public school children, hospital patients, military personnel and recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and other welfare.

But this food system changes slowly. Contracts are locked in far ahead of time, and most institutional kitchens are still built around shelf-stable foods because they are cheaper and easier to manage. Will the new standards be applied at the scale the language implies? The answer is in the fine print: procurement rules, budgets, staffing levels, kitchen equipment and, ultimately, what schools and other institutions are actually permitted to serve.

The biological reality is that health improves when most of our calories come from minimally processed food, protein is adequate and spread across meals, added sugars and refined starches are rare, and whole-food fats replace industrial fat-and-starch mixtures. These improvements multiply when combined with daily movement, stable sleep and lower stress.

Here’s the truth: The 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines move things in the right direction, but they’re still shaped by compromise within a system that profits when people remain unhealthy. That is not a reflection of this administration’s intent. In fact, the new guidelines represent the largest federal shift toward metabolic reality in decades. They identify the primary driver of disease and finally simplify the message around whole foods.

The real test is what happens next. If these changes make it into schools, other institutions and family dining rooms, we could finally decrease obesity and disease rates. If not, the document becomes another footnote in history. What matters is what we do now.