Germany, Greece and the Fight for the Euro

For the last five years Germany has dominated the eurozone in what Der Spiegel called an “economic … Fourth Reich.” Its power has been astonishing, forcing out heads of state and dictating the laws of its southern vassals. No one has dared fight back. Until Sunday.

On July 5, the Greeks unleashed a fight for the eurozone, threatening Germany’s dominance.

We are at a new stage of the eurozone crisis. In the days ahead that may not be immediately obvious. The Wall Street Journal wrote, “The only certainty now is uncertainty.” There are a number of directions this could go. We could see a sudden escalation of the fight. Or Germany may give ground for now, postponing the major battles until later. There are even some signs that we could see a quick capitulation by Greece.

But unless there is a quick Greek surrender, Germany is now engaged in a fight that will radically transform its power.

Why? Germany’s weakness has just been exposed. It has been ordering around southern Europe. Greece just said no. Now the rest of Europe waits to see what Germany will do about it. Are the Germans all bluster, or do they have real strength? Germany could give in to Greece without suffering much. But if the rest of Europe sees a tiny impoverished nation defy the might of Germany, get away with it, and prosper, Germany’s power will evaporate.

Yet dealing with Greece is very difficult. Germany has reached the limits of what it can force Greece to do using economic power. The nation is so poor that threatening additional poverty or the uncertainty of a euro exit no longer holds the terror that it once did. Germany cannot control Greece this way anymore. As Stratfor ceo George Friedman notes in his book Flashpoints (emphasis added throughout):

How does Germany compel repayment of debts through purely economic means? The logic here leads to either capitulating economically, difficult for the Germans, or moving towards some sort of political option. There is in Germany’s reality a slippery slope where the desire to work within the EU and the desire to work only from an economic standpoint become unsupportable, and Germany either accepts the consequences of defeat in the debt game, or moves beyond economics. Hannah Arendt, a postwar philosopher, once said that the most dangerous thing in the world is to be rich and weak.

This is where we are now. But Germany’s interests demand that it controls Greece. The forces that pushed it to create its Fourth Reich still exist.

Before we go further, it’s important to note the flaw in the war metaphor used so far and to understand why Germany now rules a Fourth Reich. It is easy to see this as plucky Greeks against evil Germans. That’s not the case. The Greeks, with their borderline corrupt socialist state, have helped dig their own grave by building up debt for years. There are faults on both sides.

Both sides are locked in a currency block with opposing interests. Neither really wants to fight the other. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has not created a Fourth Reich out of a maniacal desire to rule southern Europe. Instead the euro, and the elites behind it, have set Greeks and Germans at odds.

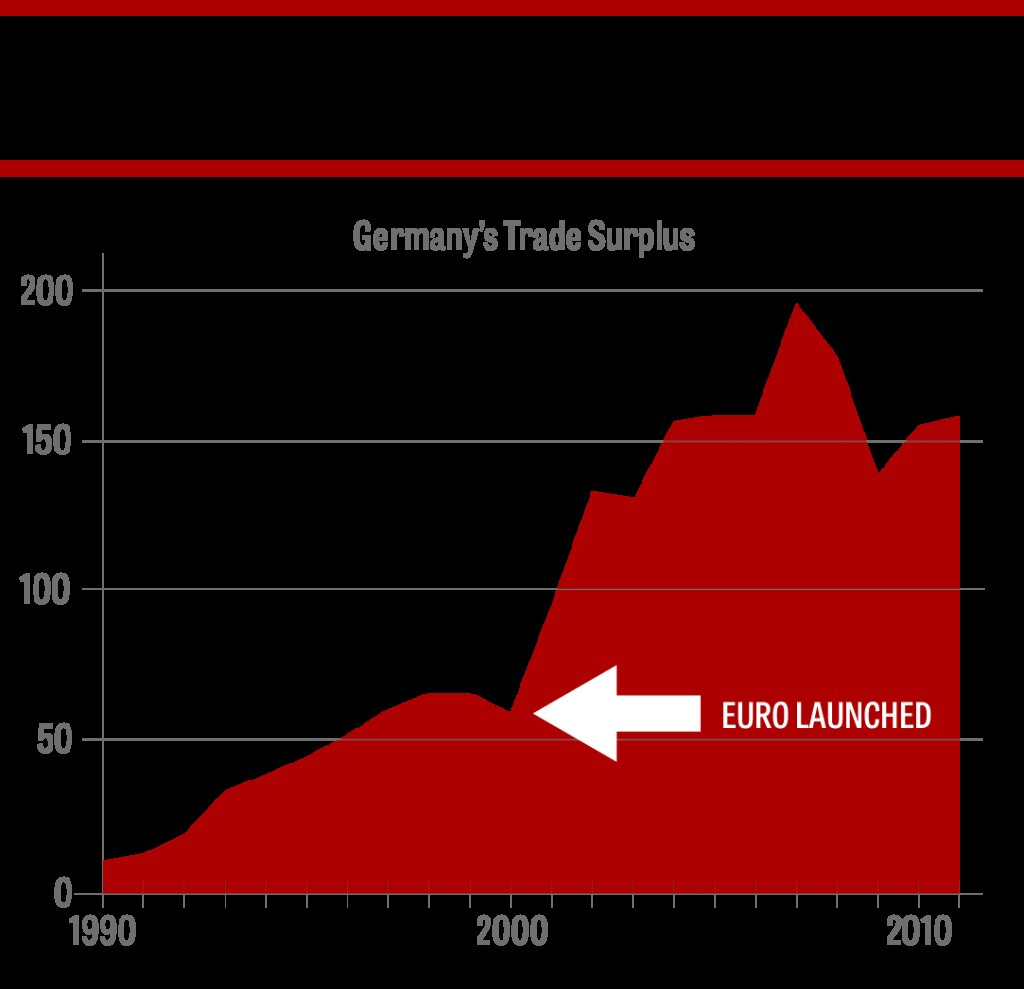

For the last five years, Germany has created this new reich, not through Ms. Merkel’s desire for conquest, but simply by following its economic self-interest within the eurozone.

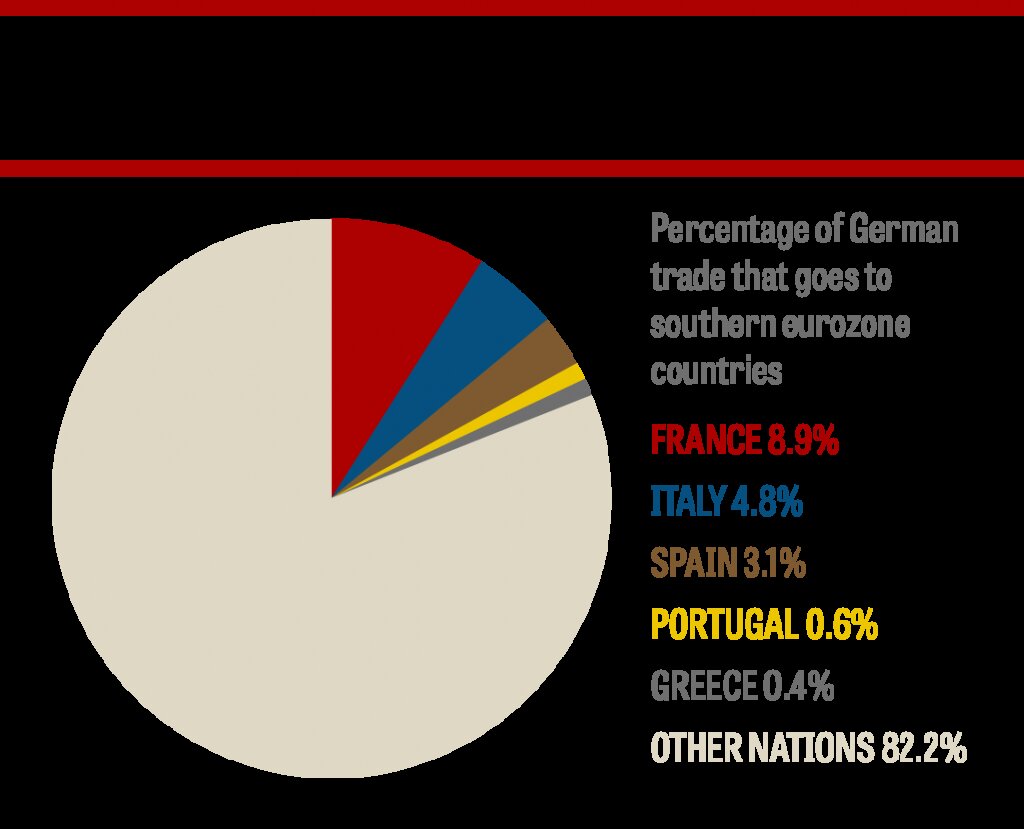

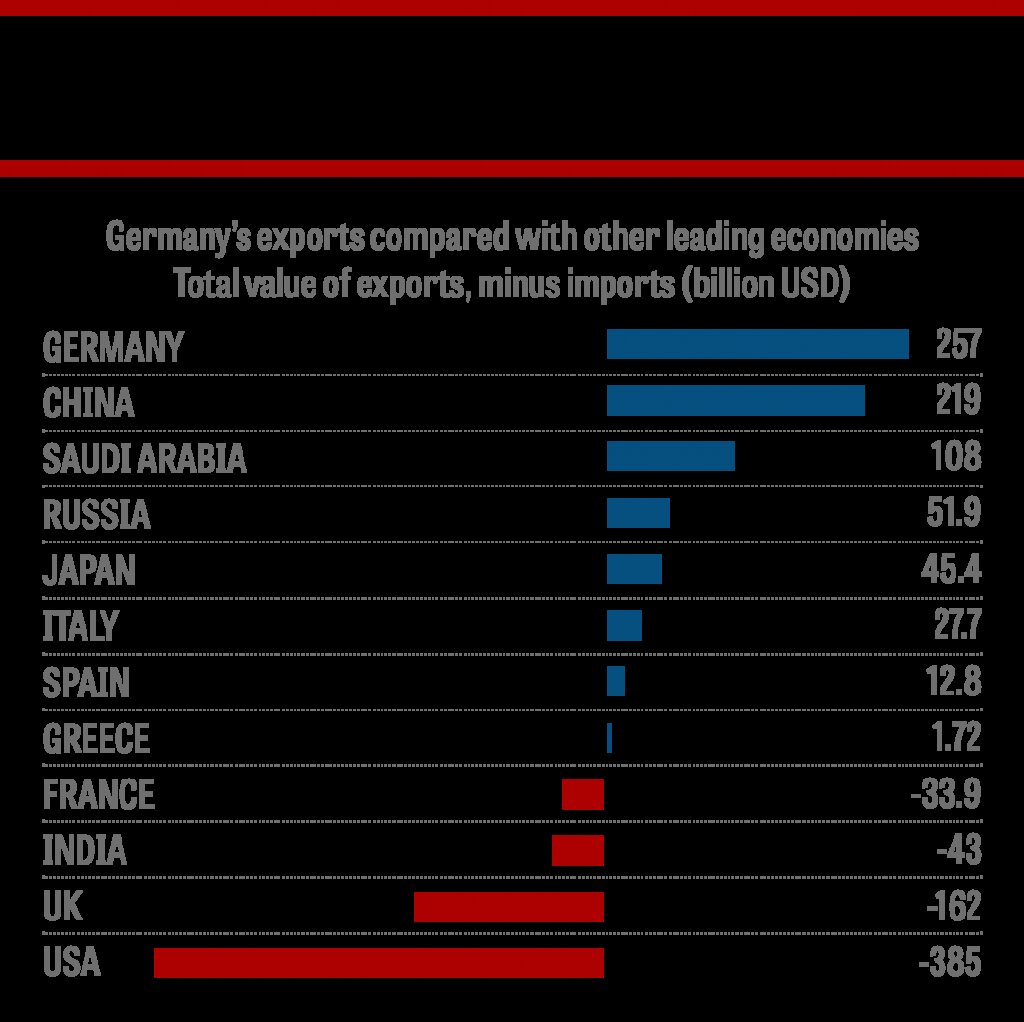

Germany has two aims. The first is to preserve the euro as a free-trade zone. If southern European nations break away, they would slow or even block the flow of German goods to their countries. This would be a major threat to Germany’s economy.

The second aim is to protect taxpayers’ money. Part of this is ensuring any bailout money is paid back.

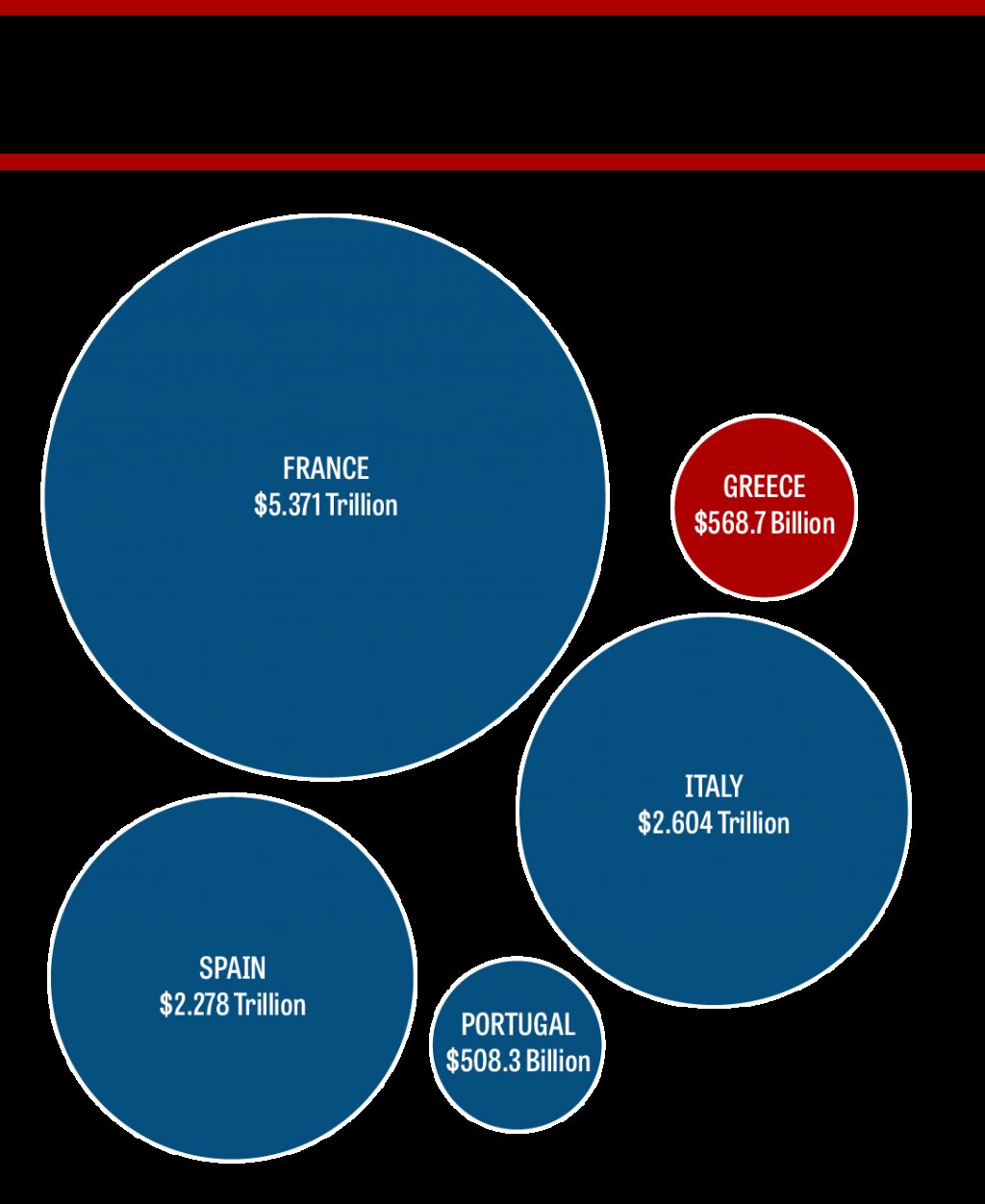

Greece, in itself, is not a major threat to either of these goals. Its economy is small. Writing off Greek debt could cause a political crisis in Germany, but not an economic one. The real threat is that it could blaze a trail for others to follow. If Greece leaves the euro and prospers, or gets its debts written off, other bigger, richer nations will follow the same path.

These aims led Germany to loan Greece and others cash, and then to control how they spent that cash, taking over a great deal of Greece. Yet now Greece is threatening both of these core aims.

The Greek government is prepared for a fight. Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis told the Telegraph that the country has a six-month supply of oil and a four-month supply of pharmaceuticals. If the European Central Bank (ecb) forces Greece out of the euro, it has said that it will take the ecb to the European Court of Justice (ecj), dragging out the crisis. Greece will almost certainly lose—the ecj doesn’t worry much about what the law actually says, it just rules in favor of Europe. But such a court case could bring months of uncertainty.

Finally, if Greece plays its cards right, it could end up leaving the euro in such a way that it leaves all its debts behind for the European Union—which ultimately means Germany—to pay.

If Greece can get away with that, then the rest of southern Europe will try it too.

This would be an unmitigated disaster for Germany. With southern Europe out of the euro, Germany’s export-led economy would be in major trouble. Unemployment would soar. At the same time Germany would suddenly be saddled with huge debts from other countries. The German government would collapse as mass protests filled the streets. This is the worst-case scenario Germany is fighting.

To sum up, if Germany does not control Greece, it faces economic ruin. Yet it can no longer control Greece using economic power. So what is Germany to do? Develop more ways to control Greece. As Friedman wrote, “Germany either accepts the consequences of defeat in the debt game, or moves beyond economics.”

Germany needs to keep Greece paying off its debt. If this fails, it needs to make not paying the debt so painful that other nations aren’t tempted to follow suit. It needs to prevent Greece from quitting the euro and then flourishing, encouraging other nations to follow. Yet it also needs to prevent Greece from leaving Europe’s sphere of influence for Russia, or any alternative power. How can it accomplish all this with only economic power?

Friedman forecast something similar to this crisis. Germany, with its memories of what it did in World War ii has held back from being more than an economic power. Nation after nation has called out for Germany to provide more leadership for Europe, both in the euro crisis and the Ukraine crisis, and others. American leaders are often telling Germany to spend more on its military, to play a more active role in the world.

Germany has refused to do so because it fears repeating World War ii. But Germany is now in a fight for its economic future. “Wealth without strength is an invitation to disaster,” writes Friedman. This is Germany right now. It has wealth. It has many of the components of strength. What it lacks is the most important—strong leadership. Without that leadership marshaling the German potential for strength, it is vulnerable. Friedman continues:

What will happen in the part of Europe that is in depression, with over a quarter of their workforce unemployed, and where massive debts have to be repaid? Political movements will merge that demand, first, that the debts not be repaid, second, that the scoundrels who created the debts be punished, and third, that what wealth there is be made available to the rest.

This is what we see in Greece already. It will spread. And notice what comes next:

A desperate nation will take desperate action. When steps are taken against a rich and weak country, there is little risk. As anti-German, anti-austerity sentiment rises, Germany, with vital interests, investments, markets and so on, will become a target and attacks on its interests will escalate. Germany will have a choice of accepting the punishment or using its vast resources to transform wealth into power. Nations do not become strong because they feel like it but because they must. Germany will face stark choices, and increasing its strength in all dimensions will become more bearable than the alternatives.

Germany will therefore become a full-fledged power, first flexing its political muscles and in time its military ones as pressures develop.

This is the end of the path Greece has begun by confronting Germany. In the long run, Germany must either give in or develop real strength to back up its economic power. Germany has an economic reich. But reichs cannot be defended by the economy alone.

As with so much of this crisis, it may have to get worse before it gets better. Ordinary Germans will have to feel that their financial security and standard of living are under threat before Germany changes. Yet this is exactly what the euro crisis threatens.

It may take time for this threat to become obvious. If Greece leaves the euro and returns to the drachma, initially it will be very painful. No nation will be tempted to follow. The threat comes in a year or two. If Greece is, by then, thriving, then other nations will threaten Germany’s core interests by considering the same path.

And remember, the euro is just one of several potential crises. The Bank of International Settlement is warning that the debt-addicted Western world could be heading for a major economic crisis, with no lifeboats. And on the non-economic front, Russia’s resurgence, and the instability that is creating, is another trigger Friedman points to that will prompt German remilitarization.

Earlier in the euro crisis, Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry wrote:

Immediately after the Greek bailout was announced, gold prices soared to their highest level ever. It was caused mostly by Germans buying gold. They remember the hyperinflation in their recent history. They know that the euro is becoming a weak and unstable currency.

About 90 percent of the German people are very hostile toward the bailout. They are alarmed because they know that Germany will have to carry most of the financial burden. The people are fearful about their future. When Germany is strong and the people are alarmed, all of us should be alarmed—especially in a crisis like this. If you understand German history, you know that the Germans are decisive when facing serious crises. History shows that they have repeatedly turned to a very strong leader to deal with a potential or real crisis.

By standing up to Germany, Greece is bringing the crisis home to Germans. It has barely affected them so far. Germany’s unemployment is low and its economy is thriving. But if Germans see southern European nations threatening to destroy the trade area their economy relies on, while saddling them with hundreds of billions of euros of extra debt, they will become alarmed very quickly.

The Trumpet, and the Plain Truth before it, have given numerous warnings about what to watch for in the future of Europe. The most important of these are:

In the euro crisis, we’re seeing every one of these come about. For more information on these warnings, read our free booklet He Was Right, starting with the first chapter, “Is a World Dictator About to Appear?”