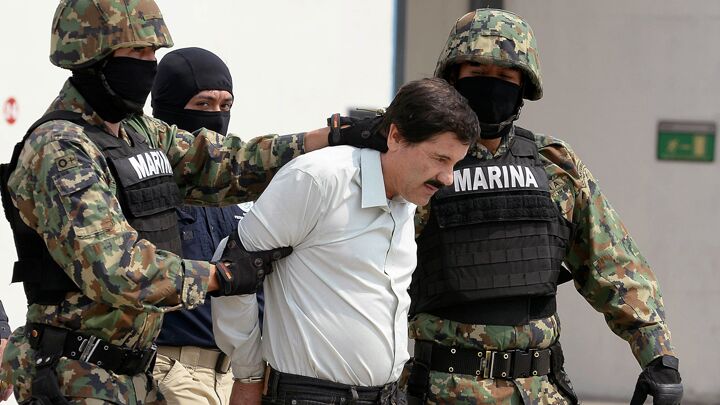

Mexico Takes Down Most Wanted Drug Lord

Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the Mexican drug baron who headed the Sinaloa Federation, was arrested February 22. The arrest was cause for celebration within law enforcement circles on either side of the border, and it certainly earned Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s beleaguered government some credibility scores.

Guzmán was arrested in 1993 for drug trafficking crimes, but his imprisonment became a huge embarrassment for Mexico. Prison didn’t prevent El Chapo from running his business. He even had prostitutes brought to him in prison. He bribed security officials until his eventual escape in 2001.

As a fugitive, Guzmán consolidated his narcotics business into a robust international enterprise whose tentacles reached as far as the drug markets in Europe, Asia and Australia. Locally, the Sinaloa Federation controlled the greatest geography of any Mexican cartel, rivaled only by Los Zetas. Thus, the Sinaloans controlled many of the trade routes into several U.S. cities.

Chicago was Guzmán’s main base of operations in the United States. In February 2013, the city declared him Chicago’s Public Enemy No. 1, though he’d never set foot there.

El Chapo held other ranks too. He was on the Drug Enforcement Administration’s most wanted list—the world’s most wanted drug baron with a $5 million bounty on his head. He ranked 67th on Forbes’ 2013 list of the most powerful people in the world, and 701st on its 2009 list of billionaires.

That such a powerful drug kingpin is now out of business should be a legitimate cause for celebration.

But not everyone is breaking out the tequila in victory celebrations.

“It’s like time stood still,” wrote journalist and author Javier Valdez, following Guzmán’s recent arrest. “There is a feeling of uncertainty, a worry of what could come next.”

Welcome to Mexico’s drug culture.

In 2009, Trumpet columnist Brad Macdonald wrote an incisive piece about the state of affairs south of the U.S. border. Titled “Mexico: Bordering on Collapse,” his article essentially declared that Mexico is a failed state. If you read what Mr. Macdonald wrote over 5 years ago and compare it to what’s happening now, you’ll come to the same conclusion.

Recent history suggests what could come next for Mexico following Guzmán’s arrest. One of the main constants in Mexico’s drug war is that eliminating cartel bosses often leads to more violence. That violence may stem from intra-cartel wars in which subordinate crime bosses battle for succession. It may also stem from rival cartels seizing such opportunities to gain more territory in inter-cartel turf wars.

The Sinaloa Federation itself is a case in point. Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo is considered Mexico’s first drug lord. He founded the Guadalajara Cartel in 1980. When he was arrested in 1989, his organization split between Chapo Guzmán, who headed his business in Sinaloa, and Gallardo’s nephews, who headed the business in Tijuana. These splinter cartels collaborated at first, but it wasn’t long before they became vicious rivals.

Los Zetas is another example. It started off as the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel, recruited from the Mexican Army specifically to fight the Sinaloa Federation. After law enforcement officials arrested the Gulf Cartel’s boss, Osiel Cárdenas, in 2003, and after he was extradited to the U.S. in 2007, the Zetas turned against their masters and declared independence.

The Los Zetas’ chief rivals are the Gulf Cartel and Guzmán’s Sinaloa Federation.

All these cartels are brutal organizations, but the Zetas appetite for gory violence boggles the mind. In a 2012 article titled “Why Arresting ‘El Chapo’ Might Be a Bad Thing,” former Air Force Special Agent and author of Cartel: The Coming Invasion of Mexico’s Drug Wars, Sylvia Longmire, went as far as saying that Mexico was better off with Guzmán as a free drug lord to keep the Zetas in check. She wrote that Guzmán “has a better chance of eventually stabilizing Tamaulipas—the epicenter of Zetas-related violence—by propping up what’s left of the [Gulf Cartel] and acting as a bigger buffer to Los Zetas, who are irrational loose cannons. Their [Los Zetas’] brand of violence currently poses the largest transnational criminal threat to both Mexico and the United States.”

It’s unlikely that Guzmán’s arrest will do much to improve Mexico’s drug violence, and it could even exacerbate aspects of the situation. Many analysts realize this. Time quipped the following on February 23: “Cheers, tears and fears follow the arrest of drug kingpin Joaquin Guzmán.” Stratfor’s analysis on the subject shows how “El Chapo’s arrest poses new risks of violence” (February 22). As Guzmán’s likely replacement, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, once said in an interview in 2010, “When it comes to the capos, jailed, dead or extradited—their replacements are ready.”

This is why Mexico is a failed state bordering on collapse. Drug violence is beheading Mexico.

El Chapo was a big part of the problem, but he was not the main problem. The main problem is America’s “insatiable demand for illegal drugs,” as Hillary Clinton affirmed in 2009. It’s all about human nature and basic economics. Mexico’s drug wars—which often spill over into the U.S.—will continue as long as the market for narcotics remains strong. Unfortunately, that market will keep growing stronger, following recent marijuana legalization laws in the United States.

What we can learn from Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s arrest is the importance of dealing with the real problems in the drug war: the drug market and human nature. For the solution to these woes, consider our articles, “Mexico: Bordering on Collapse,” “Beheading Mexico” and “Don’t Read This Article!”