The Oil Price Risk to the Global Economy

Often it’s not obvious how the stories we cover will immediately affect you. This one is different. A series of world events could soon lead to you paying much more money to fill up your car.

Of course the implications spread much further than that. The world’s economy runs on oil, and high oil prices will have dramatic implications.

Starting on Thursday, the United States will ban Iran from selling any oil anywhere in the world. Anyone who ignores the ban risks the punishment of blocked access to the U.S. economy.

Since the U.S. reimposed its latest sanctions against Iran in November, it granted waivers to eight nations to continue buying oil from Iran. In March, China, India, Japan and South Korea imported 1.6 million barrels per day from Iran. But on May 2, those waivers will expire, and the U.S. has said it will not extend them. Experts expect Iran’s total oil exports to drop to 600,000 barrels per day once the new restrictions hit.

That’s great for putting pressure on Iran. But it reduces the global oil supply by around 1 million barrels per day.

At the same time, the U.S. is squeezing the regime of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro as Venezuelans suffer grinding poverty from failed authoritarian socialist policies. U.S. sanctions came into force on Sunday, targeting the government-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela. Even before the sanctions hit, America’s oil trade with Venezuela had collapsed. In 2008, Venezuela was producing more than 3 million barrels a day. By March 2019, production had fallen to 840,000, and then the latest sanctions hit.

This is great for pressuring the Maduro regime and standing up for the people of Venezuela, but it is not great for oil supplies.

Meanwhile, violence is raging in North Africa. If the civil war worsens in Libya, their 1 million barrels per day may not make it to market. Unrest in Algeria would interrupt a similar amount of trade.

Saudi Arabia has promised to make up the shortfall. But it won’t be quick to actually carry it out. It responded quickly in November, when the initial sanctions on Iran hit. However, the U.S. granted more waivers than the Saudis expected. Instead of saving the world from expensive oil, they ended up selling their dwindling supply at bargain prices, and they are not keen to make the same mistake again. There are also questions about how much oil Saudi Arabia can pump. Its government-run oil company, Saudi Aramco, opened its books this month, revealing that its Ghawar oil field is more depleted than many thought.

“Global spare capacity is arguably as low today as it was during the great oil shocks of the last half century,” wrote the Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard. “We are skating on thin ice.”

He cited Westbeck Capital’s Jean-Louis Le Mee warning that the spare oil capacity will fall to 1.2 million barrels a day by the autumn. “This will not be enough to cover demand even if nothing goes wrong, and a great deal is likely to go wrong,” Evans-Pritchard warned.

Brent crude hit a six-month high last week, above $75 a barrel. Prices have increased by around 40 percent since January. Bank of America warned, “We see a risk of $100 Brent by year-end.” Few are prepared for such high oil prices, “so the theatrics could be spectacular,” Evans-Pritchard wrote.

It’s far from a forgone conclusion that we are facing a catastrophic rise in oil prices—though a general rise in prices seems likely. Regardless, it is a reminder of how dependent the global economy, and therefore everyone’s welfare, is on this single commodity.

Most of us drive. Most commute to work. In the U.S., the average commute is 26 minutes each way. If fuel prices increase, most of us can’t cut back on our commute, so it will directly reduce our disposable income. And thus affect the global economy.

Even if you cycle to work, you will still be affected. The agricultural industry is more dependent on oil than any other sector, except transportation. Farm machinery runs on oil. Many agricultural chemicals are made using oil, or natural gas, which is generally affected by oil prices. Whether food or goods, almost everything you buy contains materials derived from oil and gas, is produced by machines that use oil and gas, and is transported by ships, airplanes and trucks that use oil and gas.

“International fuel and food prices are closely linked historically,” wrote the International Food Policy Research Institute. “Rising oil prices were closely associated with the 1972–74 crisis and indeed were arguably the dominant factor.” The institute argues that high oil prices probably played a major role in the 2008 food crisis, which shook governments in Third World countries across the world.

This is why fluctuations in oil prices draw so much attention.

In the U.S., there is one important change to this dynamic that has developed in recent years. The fracking boom means that the U.S. is now the world’s number one producer of crude oil. The U.S. still consumes 2 million barrels per day more oil than it produces. But since it produces so much oil, some Americans will benefit from the higher prices. Fracking is expensive. Oil companies have had to borrow heavily. Higher prices could help keep these companies in business and even expand, keeping Americans in jobs.

The fact remains that oil prices affect many—and while some areas may be winners, high prices threaten the American and global economies.

The world’s prosperity can be put at risk by the price fluctuations of just one commodity.

And it is very easy to attack that commodity.

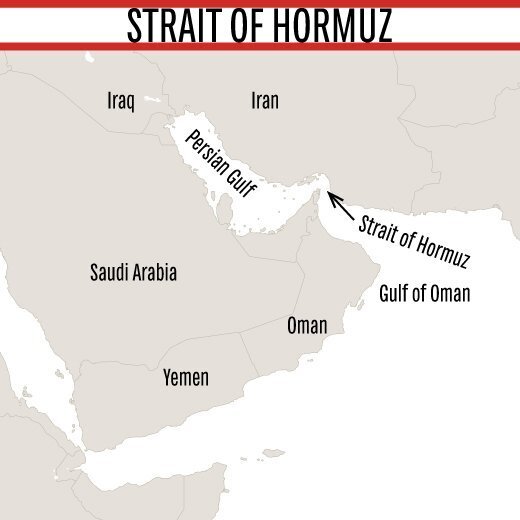

A lot of oil travels through narrow ocean passageways. Roughly two thirds of the world’s oil travels over the oceans to reach its final destination. And one third of that seaborne oil travels through the Strait of Hormuz, a 21-mile-wide sea gate controlled by Iran.

After U.S. President Donald Trump announced that all nations must now comply with the oil embargo on Iran, Gen. Alireza Tangsiri, commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy, threatened to close the strait. Iran doesn’t have to permanently close the strait to cause a lot of damage. Just closing it down for weeks or days would cause major delays, soaring oil prices, and other problems.

And Hormuz isn’t the only choke point. The South China Sea—where China is quickly gaining control—also serves one third of the world’s ocean-going oil. About 10 percent passes through the Suez Canal and the nearby sumed pipeline. And 5 percent passes through the Bab el-Mandeb, where Iranian-backed terrorists are trying to gain a foothold (and where the U.S., United Kingdom, France, China and Japan have military bases).

Now that America produces most of its own oil, it is under much less risk of being starved of this vital commodity. But the high oil prices that would result from the closure of any of these passages could still take a chunk out of the global economy.

Bible prophecy indicates that this vulnerability could play a major role in world events very soon. Iran has the ability to close the Strait of Hormuz. Cutting off such a waterway is much cheaper and easier than keeping it open. Iran just needs to lay enough mines or retain enough fast patrol boats that no tanker crew wants to risk their lives running the gauntlet.

America may not be getting any of the oil that’s affected. But such a shock would send global oil prices skyrocketing. The price of oil in the U.S. would rise along with everywhere else.

Daniel 11:40-45 tell us that Iran, “the king of the south,” will get control of Egypt, Libya and Ethiopia. This would give it control of many of the world’s major oil choke points. Control of Egypt would mean control of the Suez Canal. Control of Ethiopia would probably include control of the horn of Africa and the Bab el-Mandeb. Libya is an oil-producing nation in its own right and would provide Iran with a strategic base on the Mediterranean. Iran virtually controls Iraq, the world’s fourth-largest oil producer.

Daniel 11 describes this king of the south pushing against a German-led “king of the north.” America is not mentioned. “Arab-Iranian control over the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea could be the real reason the U.S. is not involved in this Mideast war in Daniel 11,” writes Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry in his booklet The King of the South. “Our economy is shaky, the dollar is extremely weak, and Iran could threaten or even cut off all our oil and wreck the U.S. economy to keep America out of the war.”

As far back as December 1994, Mr. Flurry speculated that an attack on global oil supplies by Iran would have huge ramifications. It “could help trigger a collapse of the Western world’s weak currencies,” he wrote. “This in turn could cause Europe to quickly unite into the most powerful economic bloc in the world. That very event is prophesied to occur in your own Bible!”

Daniel 11:40 says that Iran will “push” at Germany. In one of the earliest Trumpet issues, September-October 1990, Mr.Flurry wrote about this verse: “The Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament says the word push means ‘to strike—used of horned animals,’ or ‘to push with the horn.’ It is ‘used figuratively of a victor who prostrates the nations before him.’ It also means, ‘to wage war with anyone.’ Push is a violent word!”

It’s a perfect description of Iran’s provocative foreign policy—backing terrorist groups around the world, threatening to wipe out Israel, developing atomic weapons.

The global economy depends on oil. You can depend on a pushy Iran using that to its advantage.

For more on this prophecy, and on this critical passage in Daniel 11, read our free booklet The King of the South. This booklet will help you prove that Daniel 11 is about the Middle East today. It will show you that the Bible is a now book—packed with details that apply to the world around us. And it will show that the seemingly depressing news all around us is actually part of a glorious plan God is working out here on Earth.

You can read The King of the South online or order a free copy, which we will ship to you with no cost or follow-up.