Disorder South of the Border

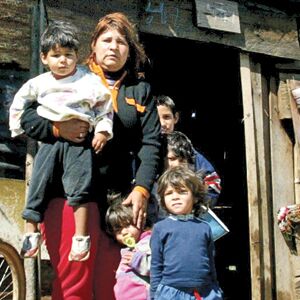

The world’s second-richest man is Mexican. His estimated net worth is $60 billion. Yet, more than 50 million people living south of the border live on just dollars per day—and the standard of living for many millions is about to get worse.

Over the past few years, Mexico has made big strides in reducing poverty and increasing the standard of living for many. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that the Mexican miracle was built on a sand foundation. The economic tide is now turning, and the current pillars of its economy—oil production, foreign remittances and low inflation—are being undermined.

Mexico is primed to boil, and the spillover could scathe the United States.

Oil’s Slippery Plunge

Mexico supplies massive amounts of oil to the United States—behind only Canada and Saudi Arabia in volume. So any interruption in the flow of oil will have huge implications for America as well as Mexico. In dollar terms, oil is the single most important revenue stream for the Mexican government, providing for a whopping 40 percent of all federal spending.

However, Mexican oil production is plummeting. Much of the problem stems from Mexico’s super-giant oil field Cantarell. Located in shallow waters off the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, this one field alone supplied about 60 percent of Mexico’s output until recently. Output peaked in 2004, after which pumping volumes drastically declined. Production cascaded 13.5 percent in 2006 and 15 percent in 2007, and 2008 looks like it may be an even bigger disaster.

Making matters worse is that for every 10 barrels of oil pumped out of the ground last year, only four new barrels were discovered. If trends continue, Mexico will stop exporting oil and begin importing it in just four to six years. A turnaround is not likely, due to a number of factors.

According to Mexican law, Petróleos Mexicanos (pemex), the state-owned oil company responsible for all the nation’s oil production, is not allowed to partner with any foreign oil corporations to look for oil on Mexican territory. This is a huge handicap for pemex because it does not have the technology it needs to efficiently explore the Gulf’s deep water. So potential resources are left undiscovered and untapped.

Additionally, since pemex is government-owned, its annual profits are used to cover government spending as opposed to exploration and development. Instead of creating future revenues, current revenues subsidize the living standards of the Mexican populace. The state requires pemex to sell fuel at prices sometimes less than half the market value. This kind of management has virtually bankrupted the company, despite the fact that oil is trading at over $140 per barrel. In 2006, pemex was the most indebted oil company on the planet.

If not for record-high oil prices, both pemex and Mexico would have already faced a severe budget crisis. With 40 percent of government revenues at risk, the whole country could have easily descended into chaos, with resultant devalued currency, rising interest rates and much higher taxes. Record oil prices have temporarily plugged the gap left by plunging production levels. But if high oil prices eventually retreat, Mexico is going to face a huge cash crunch.

For now, there are other serious ramifications.

Declining Mexican oil production means that either Mexicans or Americans will have to do without. With global oil supplies as tight as they are, either decision will have far-reaching effects.

Mexico is left with ugly choices. If it chooses to reduce exports to America, it will lose its largest source of foreign capital. Consequently, the Mexican trade gap will soar, government spending will plummet, and the peso will come under intense pressure—leading to price inflation even more severe than current levels. Yet if Mexico decides to restrict local supply in order to maintain its foreign income streams, it risks choking off local commerce by inducing local price spikes and shortages not only of fuel, but also of essential petrochemical products like lubricants, synthetic fabrics, plastics and fertilizer. A cauldron of social and political upheaval is bubbling.

Mexico’s easy oil days are over. Currently, it looks like Mexico has decided to limit exports to America, recently announcing a sizeable reduction of 150,000 barrels per day. So America’s easy oil days are ending too.

Money Not Sent Home

But faltering oil prices are not the only problem facing Mexico. Mexico’s second-largest source of foreign income, remittances from the U.S., is also wavering.

The phenomenon of Mexicans working in the United States and sending money home to Mexico is well documented. In fact, foreign money sent home from Mexicans working abroad totaled nearly $24 billion in 2006, which was over 3 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. But these remittances are going off a cliff too.

Mexican workers’ remittances decreased 2.4 percent in the first four months of this year. This was the first decline for a January-to-April period since the central bank began tracking the data in 1995, and could mark an important turning point in the structure of the Mexican economy. Add on the fact that a weak U.S. dollar means that the dollars that are sent back are worth less, and Mexicans are really feeling the pinch.

There are several theories explaining the dropoff, but it is most likely a combination of a slowing U.S. economy, a drastically reduced home construction sector, and reduced immigration due to increased border security. Regardless of cause, the effect is that Mexican Americans have less money to send home, and Mexicans have less to spend.

Inflation Problem

And falling oil revenues and foreign remittances probably couldn’t have come at a worse time, because inflation is also tugging at Mexico’s economic and social fabric.

Although the government has sought to shelter Mexicans from rising fuel prices, it has not been able to protect them from soaring food and import prices. Since 2000, the price of corn, wheat and rice have each risen over 200 percent, even spiking into the 300 percent range at times. And much of the price increases have come during the past two years. For example, cooking oil has risen 50 percent this year.

In 2007, thousands of protesters in multiple cities took to the streets to protest the rising price of tortillas.

The food situation is especially dangerous for Mexico since it relies on imports for the majority of its grain consumption, 30 percent of its corn consumption and over 80 percent of rice consumption.

The government’s solution will only make matters worse in the long run. On June 18, President Felipe Calderón announced a price freeze on 150 food items including beans, tinned tomatoes, fruit juices, ketchup and cooking oil. But artificially lowering prices has a nasty side effect. It reduces the incentive for producers to increase production. If producers cannot make a profit because the government mandates that you must sell at a loss, it makes more sense to close up shop. This is why price freezes don’t work and can actually lead to higher prices—because artificial price freezes create further shortages. If conditions deteriorate enough, and price freezes become more widespread, Mexicans won’t be complaining about the high cost of food, they will be complaining about the widespread shortage of food.

Pressure is building in America’s southern neighbor. Jim Willie, editor of the Hat Trick Letter,described how conditions in Mexico are commonly coming to include extortion-motivated kidnappings, revolutionary insurgency, murders of police officers, execution-style killings, gangster warfare and bomb attacks against oil pipelines. Willie thinks the future could be even more drastically unstable:

A failed nation state is the likely outcome south of the U.S. border. Energy network attacks, growing poverty and inequality, inadequate government services, growing power of organized crime, corruption and desertion of police forces, assassination of judges and officials without consequences, and growing farmer bankruptcy are contributing to a failed system in Mexico.

And this is coming off relatively good times, economically.

Things are going to get much worse. America’s increasingly unstable southern neighbor is facing many stressors and declining revenue, and the situation could melt down quickly. Our Mexican readers would do well to be wary of these conditions. And the amassing of tens of millions of hungry and unhappy people across the Rio Grande is sure to also affect America far beyond simply reducing oil deliveries.