Has America Waged Its Last War?

Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid were giddy like lottery winners. As last week’s election night results tipped the balance of power in both chambers of United States Congress in favor of the Democrats, these two looked to become the next speaker of the House and Senate majority leader. Throngs of supporters cheered; their faces glowed. Confetti fell; their hearts soared.

They weren’t the only ones celebrating. Halfway around the world, Iran’s leaders were also wreathed in smiles. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the nation’s supreme spiritual head, called the election result “an obvious victory for the Iranian nation.” He viewed it as “the defeat of Bush’s hawkish policies in the world,” Iran’s student news agency isna reported. Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad said the election showed “that the majority of American people are dissatisfied and are fed up with the policies of the American administration.”

Amazing: Not only were the Democrats and mullahs celebrating the same thing, they were celebrating for the same reasons. Expectations are high in both circles that an era of perceived American belligerence and warmongering is over.

What that means for the future, however, is where the two camps differ. Democrats believe this will open the door to a golden age of diplomacy—the mullahs believe it’s a step toward a golden age of their brand of Islam. The Dems see the election leading to peace—the mullahs see it as buying them the breathing room they need to take over the Middle East and beyond.

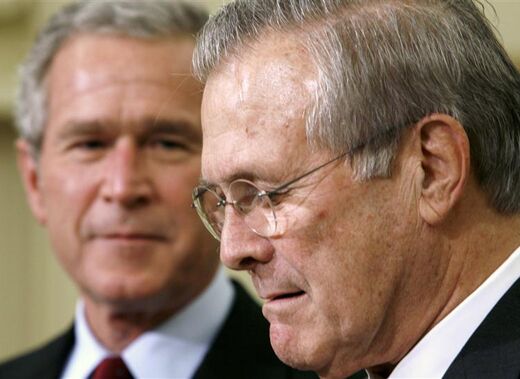

Which vision is correct will become clear quite soon, because the U.S. truly has entered a new, less militaristic phase. Donald Rumsfeld, who oversaw the campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, was out the day after the election. The man who will replace him is widely believed to favor a more pragmatic policy, one that would favor negotiating with Iran and Syria to fix Iraq’s problems. “We have to tell Iraqis that the open-ended commitment is over,” said Sen. Carl Levin, who will likely lead the Senate Armed Services Committee. He and other top Democrats immediately said they’d work to start bringing the troops home within months.

The voices of the new leading party in Congress, compelled to prove they aren’t soft on defense, say they will implement a smarter, tougher military policy. But the truth is, they represent a trend in American politics that has been developing for decades—a trend that, in the end, President Bush will have proven only a brief exception to: the loss of America’s military as a genuine instrument of American sovereignty.

In other words, America has all but given up its ability to declare war.

The Democratic victory merely poured in concrete a reality that had already existed for perhaps two years. The shift toward managing dangers through diplomacy without threat of action, of subjugating national interest to the will of the United Nations, has already occurred. Just look how Washington has handled nuclear threats from the other two members of the “axis of evil,” Iran and North Korea. Semi-tough talk backed up by firm, muscular patience. Belligerent tolerance. Repeatedly redrawing lines in the sand. Shuffling responsibility onto the UN, or the Security Council, or the EU, or six-party talks.

Even an objective observer can see the drastic adjustment in attitude from the administration that knocked out the Taliban in seven weeks and Saddam Hussein in three. Between those two impressive successes and now, something changed. Almost 3,000 American soldiers dead, perhaps; overstretched forces; Abu Ghraib; constant drubbings in the press; abysmal approval ratings; a combination of things, surely. Whatever the cause, anyone can see that the U.S. is behaving differently—already.

So now, after an election that empowered the party that has incessantly criticized virtually every aspect of those campaigns the president did undertake, should we expect a toughening of the U.S. military? No one campaigned on a strategy of increasing troop numbers and fortifying America’s presence in Iraq. When Senate Armed Services Committee chairman-elect Levin says, “The people spoke dramatically, overwhelmingly, resoundingly, to change the course in Iraq,” he is not advocating victory in the traditional sense—he is talking about some version of fleeing the scene.

After disentangling itself from Iraq, will the U.S. recommit troops in order to solve other conflicts by military means? Not outside the confines of UN or nato action, surely.

Will it go after Iran, North Korea, or somewhere else? No.

Will it, instead, look for every possible diplomatic avenue in addressing new global problems, to the point of effectively taking robust military options off the table? It already has.

Is it possible, in fact, that the United States will never launch another war?

To a mind saturated with hatred for the U.S., convinced that Islam will soon rise to dominate the world, the answer is obvious. The Great Satan, so powerful and arrogant, has been humbled. It will not rise again.

Last March, an important article appeared on OpinionJournal.com by Iranian journalist Amir Taheri, explaining how the Middle East is anticipating the day that President Bush leaves office. Titled “The Last Helicopter,” it described a powerful image burning in the minds of many Muslim leaders: that of a helicopter whisking the last of the “fleeing Americans” out of a hot war zone—an image that has played out repeatedly in history: “It was that image in Saigon that concluded the Vietnam War under Gerald Ford. Jimmy Carter had five helicopters fleeing from the Iranian desert, leaving behind the charred corpses of eight American soldiers. Under Ronald Reagan the helicopters carried the corpses of 241 Marines murdered in their sleep in a Hezbollah suicide attack. Under the first President Bush, the helicopter flew from Safwan, in southern Iraq, with Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf aboard, leaving behind Saddam Hussein’s generals, who could not believe why they had been allowed [to] live to fight their domestic foes, and America, another day. Bill Clinton’s helicopter was a Black Hawk, downed in Mogadishu and delivering 16 American soldiers into the hands of a murderous crowd.

“According to this theory,” Taheri wrote, “President George W. Bush is an ‘aberration,’ a leader out of sync with his nation’s character and no more than a brief nightmare for those who oppose the creation of an ‘American Middle East.’ … Ahmadinejad [and others] have concluded that there will be no helicopter as long as George W. Bush is in the White House. But they believe that whoever succeeds him, Democrat or Republican, will revive the helicopter image to extricate the U.S. from a complex situation that few Americans appear to understand.

“Mr. Ahmadinejad’s defiant rhetoric is based on a strategy known in Middle Eastern capitals as ‘waiting Bush out.’ … Mr. Bush might have led the U.S. into ‘a brief moment of triumph.’ But the U.S. is a ‘sunset’ (ofuli) power while Iran is a sunrise (tolu‘ee) one and, once Mr. Bush is gone, a future president would admit defeat and order a retreat as all of Mr. Bush’s predecessors have done since Jimmy Carter.”

Perhaps Ahmadinejad doesn’t have that long to wait.