Germany Wants Nukes

Germany doesn’t want America’s old nuclear weapons—it wants to build its own. In 2009, Germany’s ruling coalition stated one of its goals was to remove American-owned nuclear weapons from German soil. Now the debate has moved on, and some want Germany to build its own nukes.

While the public is skeptical, influential news outlets on both sides of the political spectrum have published editorials promoting a rethinking of Germany’s nuclear policy.

In November 2016, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, a conservative-leaning newspaper with Germany’s largest foreign circulation, published an opinion piece titled “The Utterly Unimaginable.” In it, the newspaper’s co-editor Berthold Kohler said the “simple ‘same as before’” route couldn’t continue. The retreat of the United States and the advance of Russia and China meant the Continent was changing: Germany could no longer rely on building “peace without weapons.”

A new path needed to be drawn, Kohler indicated. One with “higher spending on defense,” the return of “compulsory military service,” and a new debate on nuclear weapons. He wrote that although it seems “completely inconceivable” to the German mind, they needed to ask the “question of our own nuclear deterrent.”

Earlier in the month, the left-leaning Spiegel Online, one of Germany’s most widely read news websites, published an article in anticipation of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump winning the United States election. Ulrich Kühn, from the Stanton Nuclear Security Fellowship, described the piece as musing “about the possibility of Germany pursuing its own nuclear weapons if nato were to break up in the aftermath of a Trump administration’s withdrawal from the alliance.”

Amidst these editorials, Roderich Kiesewetter, a Christian Democratic Union politician and a former Bundeswehr general staff officer, said similar things: “[I]f the United States no longer wants to provide this [nuclear] guarantee, Europe still needs nuclear protection for deterrent purposes.” Kiesewetter also happens to be the deputy chairman of the Subcommittee for Disarmament, Arms Control and Nonproliferation.

The Germans are not alone in their desire for Germany to have its own nukes. Writing in the National Interest, former special assistant to President Ronald Reagan and senior fellow at the Cato Institute, Doug Bandow encouraged Germany to do just that. “Rather than expect the United States to burnish nato’s nuclear deterrent, European nations should consider expanding their nuclear arsenals and creating a Continent-wide nuclear force,” he wrote.

While Germany’s mainstream politicians are not yet on board, they are similarly worried about drastic changes. Former Vice Chancellor Joschka Fischer, who belongs to the left-leaning Greens party, has made calls for Germany to leave its pacifist role. “Judging by [President Donald] Trump’s past statements about Europe and its relationship with the U.S., the EU should be preparing for some profound shocks,” he said.

Even the stable and collected Chancellor Angela Merkel (affectionately known as “Mutti,” or Mother, Merkel) is acknowledging the change. Spiegel Online wrote in “The End of the World Order as We Know It?” that within the EU:

Concerns about America’s possible pullback have hastened things that for years had seemed implausible. “I have to say,” Merkel announced after the meeting, “within only a few months, a considerable amount of cooperation has taken shape.”

President Trump’s inconsistent comments on this issue haven’t helped. On nuclear proliferation, he has taken both sides. At a cnn town hall held during the campaign, President Trump said that nuclear proliferation “is going to happen anyway.” He also told the New York Times, “[I]f Japan had [a] nuclear threat, I’m not sure that would be a bad thing for us.” Nine months later, in an interview with Germany’s Bild and the Times of London, he said “I think nuclear weapons should be way down and reduced substantially.”

In the same interview, Mr. Trump repeated his claim that “nato had problems.” “Number one, it was obsolete, because it was designed … many, many years ago. Number two, the countries aren’t paying what they’re supposed to pay,” he said. The newly confirmed Defense Secretary James Mattis has opposed the president’s view, saying the U.S. has an “unshakeable commitment to nato.”

In any case, the EU has to choose who to believe: The pro-nuclear proliferation President Trump, the pro-disarmament President Trump, or President Trump’s advisers. An alternative is to start trusting themselves—and it seems that’s their choice.

Kühn made sure to not overstate the case for Germany’s nuclear debate. In his article “The Sudden German Nuke Flirtation” he wrote:

Obviously, current German nuclear flirtations represent a fringe view, but they are an important early warning sign. These flirtations were carried by Germany’s biggest left-leaning and conservative media outlets.

Those opposed to a German nuclear program, and even the current U.S. nuclear weapons which are held in Germany, point to the clear public opinion against it. Polls from early 2016 show that 93 percent of Germans want nuclear weapons banned. Yet the German government was not among the 113 nations that voted to negotiate such a ban at the United Nations General Assembly last year. International surveys done by Soka Gakkai International showed 91.2 percent of people believed nuclear arms were inhumane, while 80.6 percent were in favor of banning all nuclear weapons. If the German public doesn’t like nukes, they simply hold the same opinion as the rest of the world.

“[E]xtreme views on nuclear matters do not always remain at the fringes,” Kühn continued. Pointing to a similar case, he wrote:

As the case of South Korea demonstrates, external shocks such as the repeated nuclear tests by North Korea in 2013 can quickly move formerly fringe positions to the center stage of public attention. Once in the mainstream, it can be difficult to put such sentiments to rest, particularly when the underlying security concerns remain.

Since North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006, the idea of a South Korean nuclear program has been gaining acceptance. According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, from 2013 to 2016, media coverage of South Korea’s nuclear debate doubled. Arguments were split nearly evenly between pro- and anti-nuclear views.

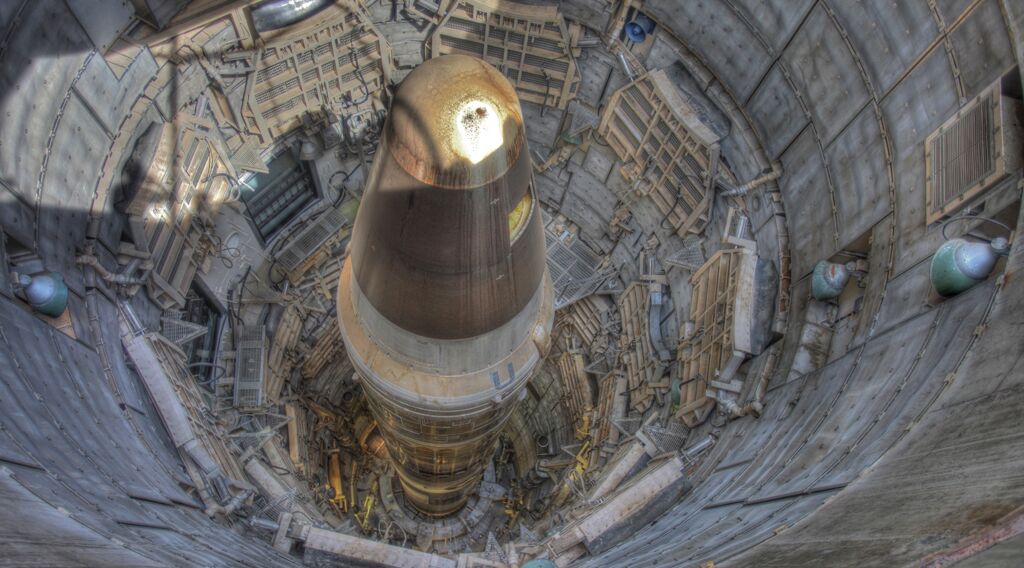

Thus South Korea is a model for how previously fringe views, which Kühn sees as warning signs, become mainstream. But while Germany restarts its nuclear debate, U.S. nuclear warheads left over from the Cold War remain at Büchel Air Base. Germany’s nuclear contradiction—a “non-nuclear” country which happens to have nuclear weapons—endures. For more on this danger, read Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry’s article “Europe’s Nuclear Secret.”