How Long Until the Euro Crisis Flares Up Again?

Europe’s economy is not getting better, and even Germany is struggling, according to the latest reports by Eurostat, the European Union’s official statistics agency.

The eurozone’s economy did not grow at all between April and June of this year, Eurostat reported August 14. Both Germany and Italy saw their gross domestic products shrink by 0.2 percent. Across the Continent, nations are being forced to reduce their forecasts for economic growth.

Meanwhile, Greece, Portugal and Spain are officially in deflation, with Italy on the brink.

Both these trends could dramatically weaken the economy of southern Europe.

This has caused its government debt to rise to 136 percent of its gdp—the third-highest level in the world after Japan and Greece. This means that for Italy to pay off its debt would require all of the country’s economic output for about 16 months. As Italy’s economy shrinks, the amount of time needed to pay off its debt climbs, even if the amount of debt stays the same.

Italy’s debt is so great that some experts are calling for the nation to give up trying to pay it. Ashoka Mody, who once worked for the International Monetary Fund (imf) designing some of Europe’s earlier bailouts, says that Italy “should get on” with restructuring its debt “right away.” Italy cannot pay back its debt on the current terms, so it should start negotiating before there’s a crisis, he advises.

Long-time Italian journalist Eugenio Scalfari said, “I must speak a bitter truth because we can all see the reality before our eyes. Perhaps Italy should put itself under the control of the troika of the [European] Commission, the [European Central Bank] and the imf.”

When this plays out on a national scale, it becomes a trap that is hard to escape. Portugal appears to be in the early stages of this trap that could spring on the whole eurozone.

Faced with these dangers, France is threatening to break ranks with Germany.

“It is hard to exaggerate the trouble that François Hollande, France’s president, now finds himself in,” Telegraph deputy editor Allister Heath wrote. “It is not just that his popularity has collapsed and that his misguided stewardship of the French economy has crippled his country, helping to deliver a second consecutive quarter of zero growth. The real problem is that France is slowly but surely emerging as the eurozone’s weakest link, together of course with Italy, and, if that were not bad enough, there is no meaningful prospect of either of the two countries extricating themselves from their appalling predicament.”

At Germany’s insistence, the eurozone has adopted rules on how much each nation can borrow each year. Struggling to bring in enough cash, French Finance Minister Michel Sapin announced August 14 that France would break these rules.

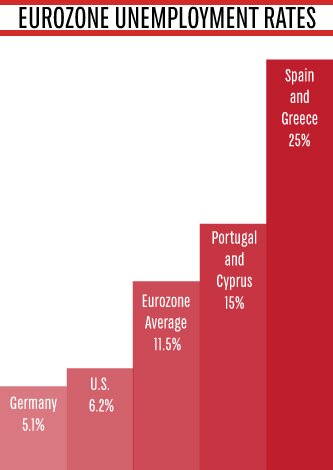

Meanwhile unemployment is the crisis that refuses to disappear. Across the eurozone, unemployment is at 11.5 percent, compared to 6.2 percent in the United States. However, this figure hides a huge amount of regional variation. In both Spain and Greece, it is around 25 percent—one in four people who want to work can’t find a job. Portugal and Cyprus have about 15 percent unemployment. In Germany, however, the unemployment rate is relatively low at 5.1 percent.

Youth unemployment is even worse. Across the eurozone, the average rate is 23.1 percent. In Spain and Greece, most young people between 16 and 25 who are willing and able to be in full-time work, can’t find a job. Italy is almost as bad.

Also, the banks are still causing problems. Portugal announced it would have to bail out its Banco Espirito Santo (Bank of the Holy Spirit), August 3, after some dodgy behavior at the company was exposed. The bailout cost $6.5 billion. The government insists that when it sells off the profitable part of the bank, there will be no cost to the taxpayer. Few believe it.

“The losses could be much larger than people think,” Megan Greene, chief economist at Maverick Intelligence, said. “This is eerily similar to what happened in Ireland, and I think taxpayers will end up footing the bill.”

“Portugal is following in Ireland’s footsteps,” Mody warned. “They are identical situations.”

“The economic impact is gigantic,” the former head of Portugal’s Banco Privado Português, João Rendeiro, warned. “It could lead to a contraction of gdp by 7.6 percent. I don’t know of any parallel to this in our economic history.”

The fact that a bank like this was able to hide its deep problems from Europe’s regulators makes investors nervous that the collapse could be repeated.

Meanwhile, Austria’s largest bank, Erste Bank, was forced to issue a profit warning on July 4, causing its share price to plunge 16 percent. Another Austrian bank, Hypo Alpe Adria, had to be split up by the government earlier this year after sucking up billions of Austrian taxpayers’ money.

Europe’s economy is awash with problems. So far, its leaders have responded to the euro crisis with temporary fixes, which have bought a few quiet months.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel didn’t want to deal with the crisis until after she had successfully weathered the German election in the autumn of 2013. The EU is currently in the process of replacing its top leaders, so it’s trying to put off making major changes until all the new leaders are in place.

But the euro is still fundamentally flawed. A block of countries cannot successfully share a single currency in the long term without a single government. The euro was designed to force European nations to come together into a superstate. Economic crises will keep exploding until these nations are forced to unify under a single government.

For more on the design behind this crisis, read Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry’s article “Did the Holy Roman Empire Plan the Greek Crisis?”