The Bible: Legend or Literal?

Can we really trust the Bible?

The Holy Book was written over the course of 1,500 years by about 40 different authors on three different continents. Its first words were penned around 3,500 years ago. For thousands of years, this unique collection of writings has been preserved, prized, parsed, weaponized and warred over. Surely no book has been hacked apart, questioned and ridiculed as much as the Bible, especially in our modern age.

Yet the Bible has stood the test of time like no other book. Why? Even those who ridicule the Bible must acknowledge that there isn’t anything else on Earth quite like it.

Does science have anything to say about the Bible? There is a field of science that has a lot to say about the biblical record. That field is archaeology.

A number of remarkable finds have been made in relatively recent history that prove Bible history—history thought originally to be of scant value at best, if not completely fabricated. Let’s examine a sample of these finds to see what the scientific records say about biblical accuracy.

King Belshazzar

The biblical character King Belshazzar is described in the book of Daniel (chapter 5) as the last king of Babylon, killed when the city fell to the Persian Empire. Historians insisted this “Belshazzar” never existed. The Bible was the only known document to mention him. Every historian worth his salt knew that King Nabonidus was the final king of Babylon and that he was not killed, but rather taken prisoner. Other historical documents clearly supported this.

This was a great conundrum for Bible believers. Could Belshazzar have been another name for Nabonidus? If so, why does the Bible say Belshazzar was killed in the attack on Babylon, when Nabonidus was documented as having been captured? Here, it seemed, was an irreconcilable difference between the Bible and ancient history.

In 1854, British Consul John Taylor was excavating an ancient ziggurat, or temple, located in the area of ancient Ur, an area ruled by Babylon, in what is now the Dhi Qar province of Iraq. There, he discovered what became known as the Nabonidus Cylinders. On these cylindrical clay documents, King Nabonidus recorded the history of the ziggurat and made a request to his god: “[A]s for Belshazzar, the eldest son, the offspring of my heart, the fear of thy great divinity cause thou to exist in his heart, and let not sin possess him, let him be satisfied with fullness of life.”

Of this discovery, Brian Edwards and Clive Anderson write in their book Through the British Museum With the Bible: “In response to an omen, Nabonidus spent many years on campaign at the oasis of Teima in northwest Arabia, and Belshazzar remained at Babylon as co-regent and thus as de-facto king” (emphasis added throughout). They explain how this reconciles other interesting tidbits from the Daniel 5 account. Verse 29 shows that Daniel was made the “third ruler in the kingdom” for interpreting the handwriting on the wall. Why the third? Because Belshazzar was the second-highest in the kingdom under his father, and third position was the best he could give! This also explains how the real ruler of all Babylon, Nabonidus, was taken prisoner while the de-facto king, Belshazzar, was killed during the invasion as Daniel records.

What an amazing reconciliation between the biblical account and scientific evidence. Even a die-hard Bible critic has to admit the Bible nailed this one.

Hittite Empire

Scripture describes Abraham burying his wife in land bought from Hittite merchants. The Hittites were allied with the king of Israel in fending off the Syrian Empire. Yet, like King Belshazzar, the Hittite Empire’s existence was claimed only by the Bible prior to the 20th century. Historians said it probably never existed, and even if it did, it couldn’t have been a very strong regional power, considering this lack of evidence.

In 1906, however, an immense, sprawling fortified city found in modern-day Turkey was confirmed to have been the Hittite capital, Hattusha. A Hittite royal library of around 10,000 tablets helped prove to archaeologists that these people were indeed the people of the land of Hatti, the kingdom of Kheta in the Egyptian texts, and the Hittites of the Bible. This massive empire controlled what later became modern-day Turkey, and its power and influence had expanded as far south as Syria and around parts of northern Canaan.

It’s one thing for historians to overlook a man like Belshazzar. It’s another thing for them to dismiss the existence of an entire empire. Yet that is what they did—and once again, the Bible’s accuracy was later confirmed.

House of David

King David is prolifically described in the Bible, yet up until around 20 years ago there was no extra-biblical evidence of his existence. Many historians and scholars considered King David a mere Israelite legend, or perhaps just a small tribal chieftain with a gloriously exaggerated biography.

But in 1993, a large stone, or stele, was discovered during excavations in the ancient northern Israeli city of Tel Dan. The victory stone, written in Aramaic, dated to the ninth century b.c.—at least 100 years after David would have reigned. It is believed to have belonged to Hazael, king of Syria, and was found in “secondary use”—broken apart and used for brickwork in an ancient building. The Tel Dan Stele reads, in part, as follows:

And I killed two [power]ful kin[gs], who harnessed two thou[sand cha]riots and two thousand horsemen. [I killed Jo]ram son of [Ahab] king of Israel, and I killed [Achaz]yahu son of [Joram kin]g of the House of David. And I set ….

This find provided the first extra-biblical historical reference to King David. It clearly elucidates victories over both what was, by that time, the northern kingdom of Israel divided from the southern kingdom of Judah, the latter being ruled by the “house of David.” Over 100 years after King David, at the time the stele was made, the southern kingdom was still identified by the name of its great patriarch.

As an aside, it’s clear from the Bible that it was King Jehu who killed kings Joram and Ahaziah. Because of the broken condition of the stele, as shown by the bracketed text, the exact names of these killed kings are not absolutely confirmed. However, the best guess is that the names do refer to Ahaziah and Joram. It would not be surprising for the Syrian king to want to take credit for killing these Israelite kings. And indeed, the Syrians had wounded Joram in battle (2 Kings 8:28-29). Also, seeing that Jehu allied himself in later years with Hazael, the Syrian king may have felt justified in claiming credit for their deaths through association.

This incredible find has had its skeptics. But after much time and careful analysis, scientists have widely come to accept it as an authentic artifact indeed referring to King David of the Bible. It also joins three other ancient artifacts bearing the term “Israel”: the Mesha Stele, Merneptah Stele and Kurkh Monolith.

Pontius Pilate

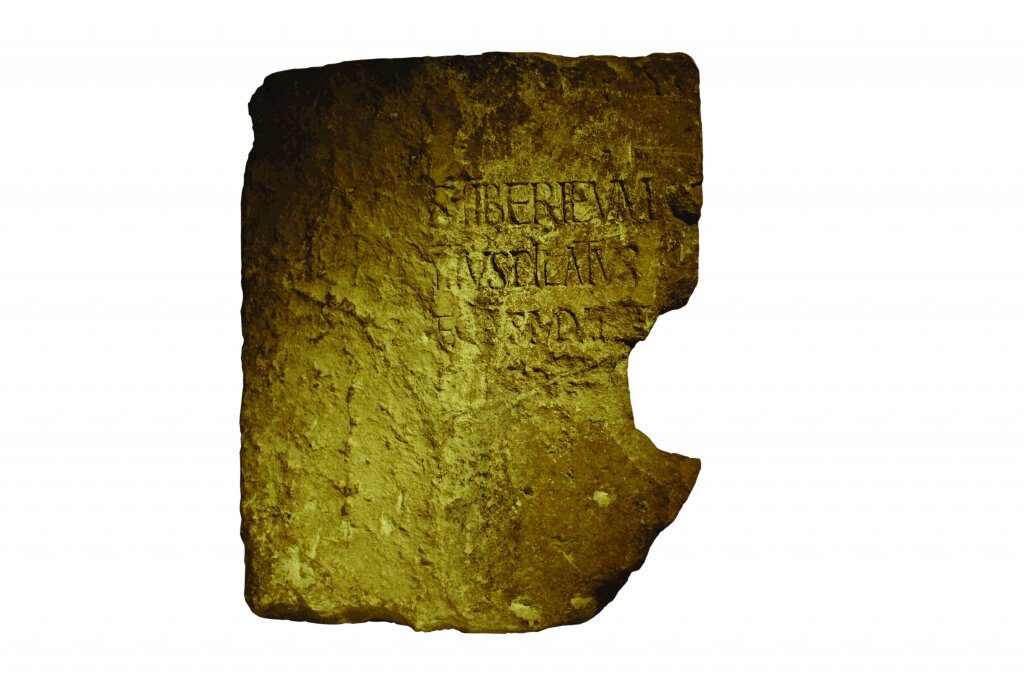

According to the New Testament, Pontius Pilate was the Judean prefect of the Roman Empire who delivered Jesus Christ to be scourged and crucified. The Bible description and later brief Roman histories were the only indications of Pilate’s existence. That is, until 1961. A unique white stone, somewhat damaged, and dating to between a.d. 26 and 36, was discovered in Caesarea bearing these Latin words:

[dis augusti]s tiberieum

[… po]ntius pilatus, [… praef]ectus iuda[ea]e, […fecit d]e[dicavit]

The English translation reads: To the honorable gods (this) Tiberium; Pontius Pilate, Prefect of Judea, had dedicated ….

While the full passage is impossible to read, the clear reference to Pontius Pilate and his governing position is unmistakable. The dating of the stone, as well as the area in which it was found, corroborates the Bible record perfectly.

Luke’s Politarchs

The physician Luke wrote one of the four Gospel accounts, as well as the book of Acts. As a well-informed, educated doctor, he wrote in a style that followed closely with his line of work—his words were precise and very detailed. Yet he has not been spared criticism. Many of his word choices had not been previously known in other contemporary sources and were questioned by scholars.

Joseph Holden writes in his book The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible: “At one time, Luke, the companion of the Apostle Paul, was viewed as an unreliable guide to the history and geography of the Mediterranean world. The writer of Luke and Acts often was alone in his use of terms, location of places, and mention of persons not known to scholarship. Such is no longer the case. He has been vindicated repeatedly, to the point that Sir William Ramsay, noted classical archaeologist, once a skeptic of the reliability of Luke, called him the greatest of historians, even above the Greek historian Thucydides.”

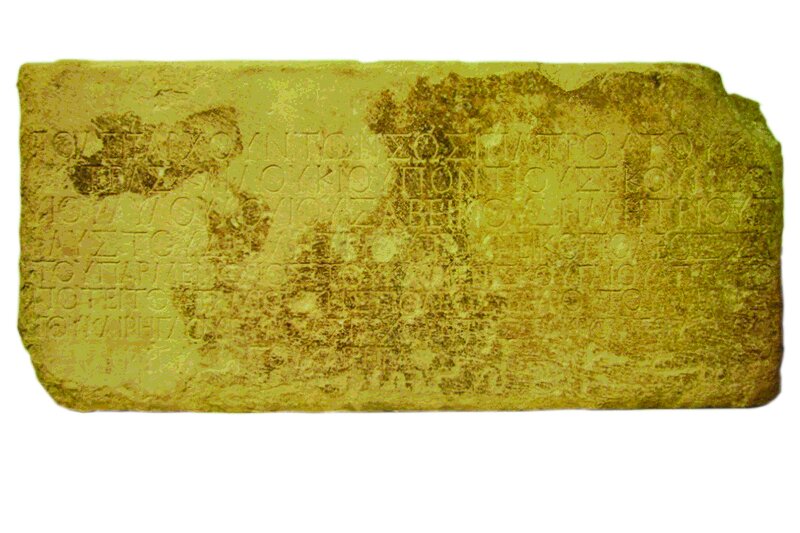

Let’s look at one example of Luke’s “language choices.” In Acts 17:6 and 8, Luke wrote, “And when they found them not, they drew Jason and certain brethren unto the rulers of the city, crying, These that have turned the world upside down are come hither also …. And they troubled the people and the rulers of the city ….” In the original Greek, Luke used an interesting term for “rulers of the city”: politarchs. This confused scholars. Luke was the only known writer to use such a title. So it was assumed that the writing must have been fraudulent, or wrong, or something in some way.

Then archaeology came to Luke’s rescue. During the 19th century, a large second-century a.d. inscription from a Roman gateway was uncovered, bearing the word poleitarchounton. This has since been shown to be from the verb politarcheo, meaning “to act as a politarch.”

This remarkable corroboration of Luke’s account is just one instance that verifies Luke’s language use. Others have confirmed terms like areopagite, grammateus, anthupatoi, bolisantes, spermologos, neokoros and others.

One could say it’s rather presumptuous for a scholar to think he knows more about a language as it was 2,000 years ago than did a trained physician who lived during the period. But such is the case with the deep skepticism and inherent bias that confronts the Bible. If the Bible describes an event not found elsewhere in history, it must be wrong. If the Bible uses a word not found elsewhere in historical writing, it must be wrong. Can such bias and immediate assumption of fiction be found toward any other work? Yet the Bible has been proved time and again to be historically accurate.

This small sampling of archaeological discoveries made in relatively recent years have shown the Bible to be an accurate, reliable document. There have always been those who doubt the biblical record, but never before has so much doubt existed in the face of so much proof! The Bible actually says that in our time today of advanced progress and “enlightenment,” there would be more scoffers than ever (e.g. 2 Peter 3:3; Jude 18). Paul foretold that these types would in particular come from today’s institutions of higher education, where students are “ever learning, and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth” (2 Timothy 3:7).

Contrary to what some might say, the Bible and science are not opposites. Science has proved this fact. You don’t have to reject one in order to believe the other.

If you would like to learn more about this astounding, scientifically proven Bible history, read our October-November 2013 Trumpet magazine (theTrumpet.com/issue/158). Also be sure to visit our website keytodavidscity.com to learn about our most recent sponsored archaeological excavations in the city of Jerusalem.

Watch out for more Bible-confirming archaeological finds to be made—the Bible actually prophesies certain discoveries to be made in the near future! (theTrumpet.com/go/11045 and theTrumpet.com/go/10910).