The Incredible Shrinking Planet

The world today is tiny. Before 1850, transmitting a message from Kansas City to Tokyo would have taken almost two months. Today it takes a few seconds. Before 1900, a journey from Philadelphia to Madrid would have taken 10 days. Today it takes eight hours. A culture that was totally unknown to the average 19th-century American—take the Vietnamese Kinh, for example—now has its own section in grocery stores, and representatives in most Western schools, universities and office complexes. Before 2000, translating a 10-page document would have taken hours of tedious labor. Today, you can use software to crudely render it almost instantly.

Planet Earth, always so vast and unknowable, has effectively been shrunk. Globalization, technological advancement, knowledge explosion and language trends are homogenizing it, blending its inhabitants into an ever more interconnected community. The integration between nations and cultures is utterly unprecedented.

What does it mean to live in a world that is shrinking so much and so fast? What will be the effect of smashing the geographic and linguistic barriers that have segregated us into distinct cultures for so many centuries? Many believe that our shrunken, interconnected, technology-saturated environment is ushering in a new age of peace among peoples. Some evidence seems to support such a view—but other factors point to a very different, far more disturbing outcome.

And Then There Was One

“Never, ever did I expect to be the last speaker of the Wichita language,” Doris McLemore said on July 10 during an interview with the Trumpet. McLemore was born 87 years ago in Anadarko, Oklahoma, where she still lives. She was raised by her full-blood Wichita maternal grandparents; Wichita was her first language.

Wichita is a difficult language—a halting stream of consonants and vowels broken by abrupt stoppages of air at the back of the throat called glottal stops. Linguists say evolving forms of it have been spoken in parts of North America for millennia.

McLemore clearly remembers a time when it was spoken by everyone around her. But now that has all been replaced by English. McLemore is the world’s last known fluent speaker. “It’s sad that the language is going to be gone,” she said.

When Wichita goes extinct, it will join a quickly growing number of languages that die each year. In the last five years alone, the world has lost Nyawaygi in Australia, Pazeh in Taiwan, Livonian in Latvia, Klallam in the United States and some 150 other languages. The rate of language death is accelerating every year. It’s now happening at an unprecedented pace.

“Something like 30 to 50 languages per year go extinct,” biologist Mark Pagel said in a January 2 interview with National Public Radio. “[W]e’re losing our linguistic diversity at a really alarming rate.”

Already, more than half of the world’s people speak just 10 common languages. And if current trends persist, Pagel says “it’s virtually inevitable that there will be a single language on Earth.”

Which language would become the “inevitable” single one?

A New Worldwide Mania

Until recently, in nations where this language isn’t natively spoken, proficiency in it was a marker of the elite. Now, it is a basic requirement for most everyone in the workforce. By a wide margin, it is the world’s most commonly studied foreign tongue. It is one of the easiest natural languages for non-native speakers to learn. It is the global media language—the primary tongue of tv, cinema and the computer world. Recent international treaties have established it as the official language for maritime and aeronautical communications. It is the lingua franca of the modern era. More than 2 billion people—almost one in three human beings—speak it daily.

The language, of course, is English.

The spread of English began during the 16th century with the expansion of the British Empire. Its diffusion was greatly intensified in the 20th century thanks to America’s economic, political, military and cultural dominance. It is now sweeping the world with what American entrepreneur Jay Walker calls “English mania.”

“English is the world’s second language,” Walker said in a recent ted talk. “Your native language is your life. But with English you can become part of a wider conversation: a global conversation …. The world has other universal languages. Mathematics is the language of science. Music is the language of emotions. And now English is becoming the language of problem-solving. Not because America is pushing it, but because the world is pulling it.”

Lately, it has become routine for lead players from Russia and China to conduct meetings about mammoth trade deals, military cooperation, and ways to end the dollar’s dominance. Do you know the language they use during these talks? Mostly English. The same is true for an increasing number of international exchanges around the globe.

University of California–Irvine professor Mark Warschauer said, “It’s gotten to the point where almost in any part of the world, to be educated means to know English.”

The Ongoing Explosion

Meanwhile, mankind is in the midst of what can only be called an explosion of knowledge and technology. Its growth is exponential.

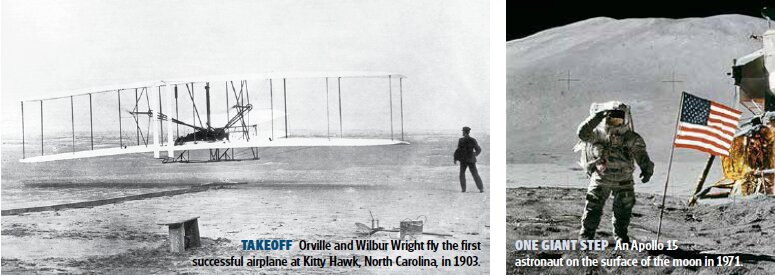

In 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright flew an airplane for 59 seconds. Four decades later, nimble Japanese warplanes bombed Pearl Harbor. Less than three decades after that, the United States landed men on the moon. So, mankind went from awkwardly gliding a few feet off the ground for less than a minute to shooting manned rockets to the moon and back—all within one human lifetime.

And from there, the speed of the exponential growth has only accelerated.

Google ceo Eric Schmidt recently said mankind now creates as much information in two days as humans did from “the dawn of civilization up until 2003.”

YouTube alone uploads more than 100 hours of video every single minute. Computer pioneer Mitchell Kapor said, “Getting information off the Internet is like taking a drink from a fire hydrant.”

The smartphone in your pocket has far more processing power than any computer aboard the Apollo 11 spacecraft. It is a better communication tool than anything President Reagan had. And it gives you access to more information than President Bill Clinton could access.

Smartphones are not just for the affluent. More than one in five human beings on the planet now own one. In Albania, it is not uncommon to see a person riding a donkey while speaking on an iPhone. In India, some beggars take breaks from solicitations to make calls on their Android devices. In the popular revolutions sweeping across the Arab world, they play a central role in informing and coordinating history-altering uprisings.

Technology has also given numerous culture-bridging options to those who do not yet speak a common language. Google Translate, ImTranslator, promt, Bing Translator and other services can provide crude translations among dozens of languages in just a few seconds—free. The translations are far from perfect (and can sometimes render comically incorrect interpretations), but even some professional translators use them as first drafts and then correct and polish the automated text.

These and dozens of other new technologies are serving as trampolines beside the language barrier, letting millions hop over it every day. Another development, Skype Translator, combines speech recognition, machine translation and speech synthesis to provide uncannily fluent, cross-lingual conversations between speakers of different languages. That means a user can speak to someone who doesn’t understand his language, and the software will translate his words and speak them to him in almost real-time. Microsoft ceo Satya Nadella said, “It is going to make sure you can communicate with anybody without language barriers.” Demos show that translations rendered by Skype Translator are startlingly accurate. The product will be released to the public later this year.

Scientists are also rapidly developing artificial intelligence, medical technology, genetic engineering, nanotechnology, data science and an innumerable list of other technologies. More than 50 years ago, Danish physicist Niels Bohr said, “Technology has advanced more in the last 30 years than in the previous 2,000. The exponential increase in advancement will only continue.”

With each passing year, those words become truer.

Stop, Collaborate and Listen

When you add the explosion of knowledge/technology to the spread of English and the accelerating pace of language extinction, it’s plain to see that the world today is tiny. Perhaps the most noteworthy result of the shrinking world has been the mass intercultural collaboration that has resulted from it.

In the pre-industrial world, it was not unheard of for large numbers of people from different cultures to work together on massive projects, but such projects were quite rare. And the definition of “large numbers” has evolved over time.

In the 10th century b.c., an unusually large group of Phoenicians and Israelites—more than 150,000—worked under King Solomon to build the first temple. In the 17th century, some 20,000 craftsmen from India, Persia, the Ottoman Empire and Europe pooled their efforts to build the Taj Mahal. In the early 20th century, 70,000 men from the West Indies, Panama, the United States, Italy and Spain collaborated to dig the Panama Canal.

But in the Internet age, tens of thousands or even 150,000 collaborators is a small number.

Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia, is the product of collaboration by more than 22 million researchers, writers and editors from all over the world. Duolingo, launched only two years ago, already has more than 25 million users in nations around the globe working to translate the Internet into other languages.

But even these colossal figures pale in comparison to the number of people working together on a particularly brilliant project called recaptcha.

Have you ever tried to order something using an Internet form and been asked to read a distorted word and then type it into a box? That is recaptcha. It’s there to prove that the entity trying to submit the form is human and not some nefarious computer bot.

But here is the brilliant part: Those words are not random. Every person who enters recaptcha text is also helping to digitize old books and newspapers. For newer publications, computers can recognize and digitize text without any human help. But for anything written more than 50 years ago, computers can only recognize about 70 percent of the words. Nothing short of a real, live human being can read the remaining words.

Every time you type a fuzzy word into a recaptcha field, you are not only verifying to the website that you are a real human being, you are also helping to digitize an old document—making it available to Internet users around the world.

How many people—knowingly or unknowingly—have collaborated on this massive online project so far?

Seven-hundred and fifty million. That is more than one in 10 of all living human beings. Put together, these collaborators are digitizing the equivalent of 2.5 million books per year.

Dawn or Doom?

Truly, human collaboration has soared to unprecedented heights. But this raises a pressing question: Is all of this development good or bad? Does it mean mankind is on the cusp of ushering in a bright new dawn, or are we edging—gigabyte by gigabyte, invention by invention—nearer to extinction?

On both sides of this question, there are passionate arguments from leading thinkers.

Entrepreneur Naveen Jain believes technological advances will solve all of mankind’s ancient problems. “There is not a problem that’s large enough that innovation and entrepreneurship can’t solve,” he said.

Theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson agrees. He said, “Technology is a gift of God. After the gift of life it is perhaps the greatest of God’s gifts. It is the mother of civilizations, of arts and of sciences.”

Albert Einstein thought mankind’s technological developments would lead to war so cataclysmic that it would “reset” civilization. “It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity,” he said. “I know not with what weapons World War iii will be fought, but World War iv will be fought with sticks and stones.”

Which side is right?

The Unfinished Skyscraper

For the answer, let’s examine the world’s first large-scale collaboration. More than 4,000 years ago, just two generations after the great Flood, Earth’s human population exploded with growth. As recorded in Genesis 10 and 11, the bulk of the people gathered somewhere in the region of what is now called Iraq (Genesis 11:2). They began collaborating on a massive project.

No communication barriers hindered their work on this project because everyone on Earth at the time spoke the same language (verse 1). This huge, single-language workforce could have accomplished virtually anything. In fact, the Creator God assessed the progress of their collaborative work, saw how seamlessly and rapidly they were advancing, and said it was clear to Him that such an integrated workforce could accomplish anything its people could imagine (verses 5-6).

God created human minds. He gave them their astounding power. He knew that with lots of people laboring together, unhindered by language barriers, the Iraqi sky was the limit.

Mankind’s ideas, creativity and innovations are consistently motivated by selfishness. For proof, consider the project that this powerful, post-Flood workforce collaborated on. Remember, they could have accomplished virtually anything. So, what did they pool their resources and put their brilliant minds together to build?

A tower.

The Flood was fresh in their memories. They knew that God had sent it on earlier generations as punishment because they had chosen to live in rebellion against Him and His law of love. What did the post-Flood people learn from that history? That they should be different from the pre-Flood people, obey God, and avoid angering Him? No. They learned that in order to continue rebelling, they should build a structure that would place them above the reach of any floodwaters in case God decided to send another one. They reasoned that if they could outclimb any future flood, then they could live their lives as they pleased and still avoid the punishment that had come upon earlier generations (Genesis 11:3-4).

This massive collaboration was as anti-God as any could be. And it progressed with stunning speed. God knew that this construction project was only the beginning. “[N]othing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do,” He said (verse 6).

God knew that virtually anything a man can imagine, mankind can accomplish! Anything a scientist, science fiction author or child can dream up—radio, cars, airplanes, microwaves, smartphones, e-mail, space travel—mankind can eventually bring about if people are able to collaborate on a large enough scale.

God also knew of one thing that would perpetually be central in man’s imagination: weapons. He knew, as our history has proven, that humans would collaborate to build ever-more-destructive weaponry.

God had a plan for mankind and a specific time frame for that plan. He knew that if He didn’t intervene with their project, then mankind would continue collaborating and would soon develop weapons of mass destruction that could and would wipe mankind out. This would interfere with His plan for humanity.

This phenomenon greatly slowed man’s ability to collaborate, and to thereby bring to life the imaginations of his selfish heart.

Babel Undone

Four thousand years later, the world has changed. Man is learning to surmount language barriers. He is overcoming geographic segregation. The segregation of humanity that God caused at the Tower of Babel is essentially being undone.

Is this against God’s will? Does it mean we have finally outfoxed our Creator? No. God knew we would eventually integrate and collaborate. In fact, He specifically prophesied the dawning of this interconnected, knowledge-saturated age we now live in. Through the Prophet Daniel, God said that at “the time of the end,” knowledge would “be increased.” He forecast through the Apostle Paul that “in the last days, perilous times shall come,” in part because people would be “[e]ver learning, and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth” (2 Timothy 3:1, 7). He condemns those who become “vain in their imaginations … [p]rofessing themselves to be wise,” though they are “inventors of evil things” (Romans 1:21-22, 30).

The modern world—interconnected and knowledge-drenched—is a fulfillment of these prophecies. It has come to be as it is in perfect accordance with God’s timetable.

God also spelled out another incredible prophecy, explaining that He would permit man’s technology to advance enough to bring about those weapons capable of extinguishing all human life on Earth. “For there will be greater anguish than at any time since the world began. And it will never be so great again. In fact, unless that time of calamity is shortened, not a single person will survive. But it will be shortened for the sake of God’s chosen ones” (Matthew 24:21-22; New Living Translation).

But now that mankind is “reconnected,” what is one of the landmark collaborative projects he has undertaken?

The atomic bomb.

Where We Are Now

Some 130,000 people collaborated on the Manhattan Project and other work that brought about the A-bomb. They came from many nations and language backgrounds. It couldn’t have happened without the theory of relativity established by the German-born Jew, Albert Einstein. Germans Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, and Austrians Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, also contributed to the groundbreaking physics theory that made it possible. Other leading collaborators came from the U.S., Hungary, Italy, Poland, Canada, the United Kingdom and Denmark.

Research and production for the bomb occurred in the U.S., the United Kingdom and Canada. So the working language was English.

Not long after the Manhattan Project, mankind developed hydrogen bombs. These fusion-powered bombs are up to a thousand times more powerful than the fission-powered atomic ones dropped on Japan.

Today, mankind has at least 17,300 nuclear warheads. Only these nuclear weapons—developed just in the last seven decades—have the potential to erase all human life from Earth and thus fulfill Christ’s mind-boggling, 2,000-year-old prophecy recorded in Matthew 24.

Could another world war happen in which these bombs are detonated?

During this age in which 750 million people can labor together on a noble project, and in which innovation and collaboration are exploding with growth, shouldn’t we expect to see rapid progress toward global stability? Instead we see the opposite: exacerbating instability in Israel, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Ukraine, North Korea, Africa, the South China Sea, Central America and elsewhere. Civilization today has no shortage of flash points that could escalate to a thermonuclear level.

And that is not the only danger mankind faces. “[I]t’s now not just the nuclear threat,” says Martin Rees, who describes himself both as an astronomer and as “a concerned member” of the human race. “In our interconnected world, network breakdowns can cascade globally; air travel can spread pandemics worldwide within days; and social media can spread panic and rumor literally at the speed of light.”

Our collaborations, our technology, our imaginations have not resolved our conflicts. In fact, they have made them worse.

Herbert W. Armstrong was a leading expert on civilization’s origins, its turbulent history and its unstable present. He wrote: “[C]ould anything be wrapped in more mystery than this world’s civilization? How explain the astonishing paradox: a world of human minds that can send astronauts to the moon and back, produce the marvels of science and technology, transplant human hearts—yet cannot solve simple human problems of family life and group relationships, or peace between nations?” (Mystery of the Ages).

These questions are burning with more relevance than ever before. And you need to know their answers. To discover them, download your free copy of Mr. Armstrong’s e-book The Mystery of Civilization.

____________________________________________________________

Research assistance by WHITNEY KELSEY and BREANNA JACQUES