A Bright Light in Diplomatic History

Three decades of war haunted both nations. Attacks, counterattacks and preemptive attacks had delivered little but shed the blood of 40,000 men in the process. One man said he would “go to the end of the world” for peace, and another outstretched his hand to guide him. What precipitated was a bright light in diplomatic history.

That bright light was Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s efforts to bring peace to one of the world’s most ancient rivalries. To this day, the Jews annually celebrate their Exodus and their independence from Egypt. And on March 26, the Jews in Israel celebrated 36 years of peace with their eastern Arab partner.

Sadly, today only a few know of the efforts of these two brave leaders. Most Westerners associate diplomacy in the Middle East with the unending Palestinian conflict and the Iranian nuclear deal. Many wonder if diplomacy can actually be effective in the Middle East.

Spirit of Communication

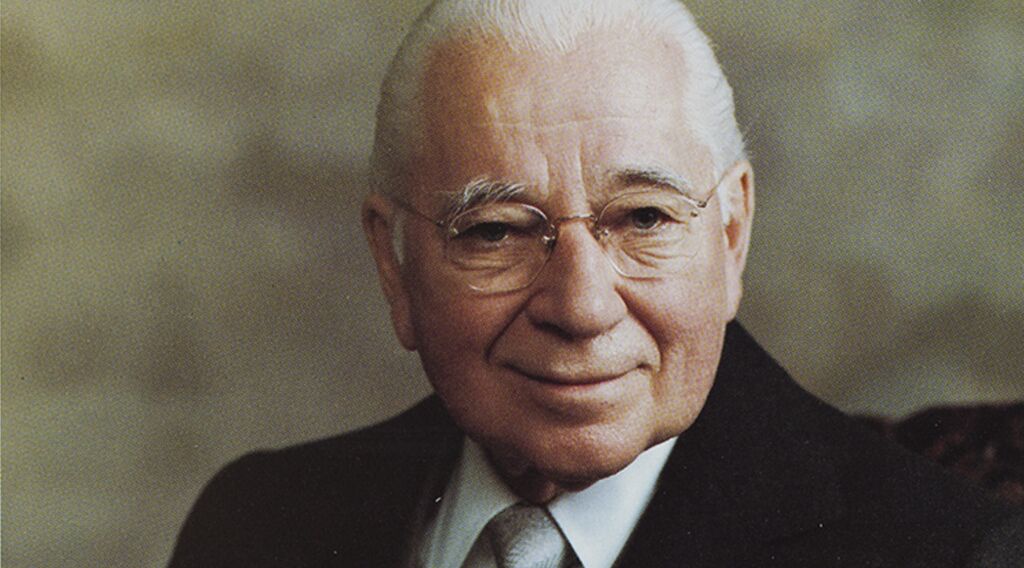

Herbert W. Armstrong was intimately involved in finding the answer to that question. He was given the amazing opportunity to be on close terms with dozens of world leaders. Beginning in 1968, Mr. Armstrong spent much of the next two decades visiting statesmen and royalty—especially in the Middle East. World leaders called him an ambassador without portfolio with a commission for world peace.

He keenly understood the ancient nature of the Arab-Israeli conflict. In 1945, after attending the formation of the United Nations in San Francisco and the first meeting of the UN Security Council in New York City, Mr. Armstrong was able to talk with leaders who supported both the Zionist and Arab viewpoints. This was prior to the establishment of the Jewish state in 1948.

In “Mt. Sinai, Jerusalem: Now Foreshadow World Peace,” Mr. Armstrong paraphrased his conversation with then president of the Zionist Organization Chaim Weizmann in 1946:

God, he said, had promised this land to the nation Israel. It had always been called “the Promised Land.” It belonged to Jews by divine right. If God ordained that Jews should be there, he, of course, had a well-founded argument. And just about everybody supposed the biblical account did affirm the divine right of Jews to have there a national state.

Saudi Arabian Ambassador Hafiz Wahba explained to Mr. Armstrong the Arab viewpoint, which seemed equally convincing:

“Do you feel,” he asked me, “that your American people have a right to the land of the United States, including California?”

”Your people have occupied this country as a nation less than 200 years, and California still a shorter time.” This was said during the San Francisco Conference. “Suppose the Japanese came claiming the land of California by divine right, and demanded they be allowed to move all Californians out and make it a Japanese national state. Would you think their claim valid? Well, we Arabs have occupied Palestine for many times 200 years, and the Zionists want us to move out and turn it over to them.”

It was this spirit of communication that promoted the success of President Sadat’s and Prime Minister Begin’s diplomacy over three decades later. Mr. Armstrong would again be personally, although remotely, involved.

The Peace Bombshell

Sadat dropped the peace bombshell on Nov. 9, 1977, when he told the Egyptian Parliament he would travel to Jerusalem to pursue peace negotiations. It was not in his original notes. Everyone in the assembly applauded, even Yasser Arafat who was sitting out front. The Egyptians loved the outreach: They believed the other Arabs had grown wealthy while the Egyptians had borne the burden of the four previous wars with Israel.

Israel quickly accepted the invitation, and Sadat was scheduled to speak to the Israeli Knesset on November 20. When he arrived, Syria declared a Day of National Mourning and flags were flown at half-mast. In Iraq, celebrations of the Eid al-Adha feast were canceled in protest. Libya withdrew its recognition of the Sadat government and severed diplomatic relations. Arab newspapers and broadcasting stations described Sadat as a “traitor,” a “capitulator,” a “conniver with the enemy” and an “agent of imperialism.”

“I have not consulted, as far as this decision is concerned, with any of my colleagues and brothers, the Arab heads of state or the confrontation states,” Sadat said near the beginning of his speech to the Knesset. “Those of them who contacted me … expressed their objection, because the feeling of utter suspicion and absolute lack of confidence … still surges in us all.”

He talked of the past, with “all its complexities and weighing memories,” but told his audience it was now time to have the “clarity of vision to overlook” it. He said:

Today I tell you, and declare it to the whole world, that we accept to live with you in permanent peace based on justice. We do not want to encircle you or be encircled ourselves by destructive missiles ready for launching, nor by the shells of grudges and hatred.

Begin agreed. “We must not permit memories of the past to stand in our way,” he responded. “I hope the day will come when Egyptian children will wave Israeli and Egyptian flags together, just as the Israeli children are waving both of these flags together in Jerusalem.”

Camp David

For a while, the attempts to put their spoken words into a written contract were bogged down. A number of times, the process nearly failed entirely. Begin, depressed from the lack of progress, began to show signs of physical decline. The Egyptian president and the Israeli prime minister worked in different ways: Sadat strove for broad demands, while Begin, a lawyer, understood the devil was in the details.

As a deal looked increasingly elusive, the United States First Lady Rosalynn Carter suggested to her husband the two statesmen be brought to Camp David—a private wooded retreat usually reserved for the American president. Unexpectedly, both agreed. President Jimmy Carter had 12 days to negotiate an agreement. Remaining in their usual contradictory fashion, Mr. Sadat came to meetings wearing relaxed sports clothes while Mr. Begin dressed formally. At some points, discussions were so heated that President Carter thought they forgot he was even there.

At the last moment, Sept. 17, 1978, an agreement was reached: Israel would sacrifice the Sinai but keep the West Bank. Egypt and Israel drew a framework for the conclusion of their peace treaty—and the peace has been kept ever since.

A Peace Center

A little over two years after the agreement was drawn up, Mr. Armstrong took a trip to Jerusalem and Egypt. When Mr. Begin remembered Mr. Armstrong had come to visit, he interrupted his meeting with government officials to drive an hour from Tel Aviv. After Mr. Armstrong apologized for interrupting the meeting, Prime Minister Begin replied, “Mr. Armstrong, I would get out of bed at 2 in the morning to see you, if necessary!”

Mr. Armstrong flew out eight days later for a meeting with Anwar Sadat. It was the first flight since the Six-Day War to travel directly from Jerusalem to Cairo. The traveling party arrived where President Sadat was delivering a graduation message at a teachers’ association ceremony. As Dr. M. Abdul-Kader Hatem, personal adviser to Mr. Sadat, joined Mr. Armstrong on the drive to the presidential palace, they saw a Cadillac ambulance following behind. The ambulance, Mr. Armstrong was told, followed the president’s car wherever it went—Anwar Sadat’s peace efforts with Israel had resulted in multiple death threats.

At the palace, President Sadat unveiled to Mr. Armstrong an architect’s rendering of the $70 million World Peace Center. It was to be located at the base of Mount Sinai. The designs portrayed “a walled complex within which were a mosque, a synagogue and a church, symbolizing cooperation between religions and between nations.” Mr. Armstrong immediately backed the plan, providing an initial $100,000 to the project and pledging a total of $1 million.

Sadat told Cairo press that he wished to see the complex “as simple and strong as he saw it in the model, so that it would express the majesty and holiness of the mount.” The foundation stone was to be laid on Nov. 19, 1981—the third anniversary of his historic peace trip to Jerusalem.

The World Peace Center never materialized. It was cut short a month before the foundation stone was to be laid.

President Sadat was attending a victory parade on Oct. 6, 1981. He had refused a military escort, instead relying on lighter security. As Egyptian Air Force Mirage jets flew overhead, a group of Islamists, led by one of Sadat’s own lieutenants, emerged from an artillery truck. President Sadat saluted, believing them to be part of the parade. The lieutenant threw three grenades while his associates mowed down the president with their AK-47 rifles. President Sadat’s tombstone would read: “Hero of war and peace.”

His death reminded the world that there were still people who detested peace.

While both Begin and Sadat began their lives engaging in war, they demonstrated it was possible to overlook the past to create a better future. In doing so, they shone a bright light in a sometimes dim history of diplomacy.

In writing of the proposed World Peace Center, Mr. Armstrong focused on the importance of its location: Mount Sinai. There, the three great Abrahamic religions look to the Prophet Moses and the Decalogue. He saw the great vision in this project: It was a tool that could point people to world peace.

Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry, who follows in the footsteps of Mr. Armstrong, delved further into the importance of this location in his booklet The Way of Peace Restored Momentarily. If you are inspired by Sadat’s and Begin’s brave moves toward peace in the Middle East, it is a must read. It describes the significance of Egypt and Israel’s historic peace pact and why the proposed World Peace Center was so important.

As diplomacy in the Middle East looks increasingly bleak, we can look back to this example of communication and cooperation. Mr. Armstrong described as “a factual story, stranger and more exciting than any fiction.” And yet, in many ways, it is the prelude to a different, and lasting, world peace.

(Listen to the episode of The Sun Also Rises about this astounding story.)