Today’s Supreme Court Would Frighten Alexander Hamilton

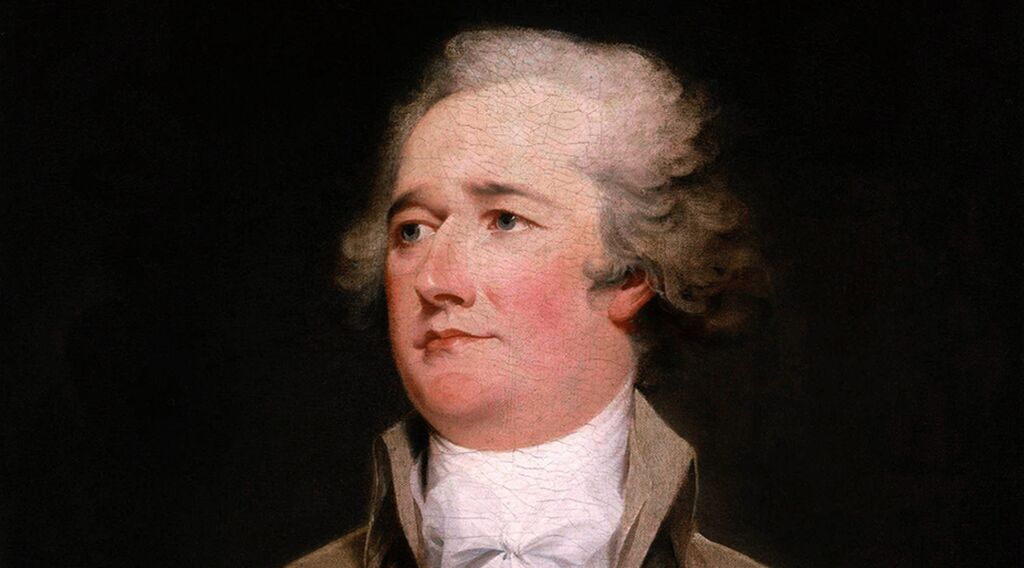

Alexander Hamilton, founding father of the United States, would likely have been disturbed by the Associated Press headline from June 28: “Supreme Court Leans Left in Term Unsettled by Scalia’s Death.” Didn’t we make it clear, he might ask, that the judiciary was to remain “truly distinct from both the legislative and executive branches”?

While Hamilton wouldn’t know who Justice Antonin Scalia was, or what the policies of the left are, he would believe that a Supreme Court “leaning” toward a legislative body is a sure step on the path to despotism.

A number of polarizing issues have been pushed through the Senate and presidency and on to the courts in a matter of days. Two cases were decided in the Supreme Court on June 23: Fisher v. University of Texas examined the extent to which affirmative action could be used in universities; and United States v. Texas examined the protection illegal immigrants’ children have from deportation. On June 27, Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt looked at restrictions on abortion procedures in the state of Texas.

Meanwhile, the biggest debate in a number of years over gun control was opened after a terrorist killed 49 people in Orlando, Florida. With the dearth of desired results from the legislative and executive branches, some have even looked to the Supreme Court to usher in their preferred policies.

For months now, conservatives have blocked a new Supreme Court appointment; they see this nomination as more important than ever before. As the Washington Free Beacon wrote:

It’s an unanticipated consequence of the outsized role the judiciary plays in our national life: The Supreme Court has become so influential that the legislative branch now has every reason to reduce its strength, and thereby its power, by not allowing new members to don the black robes.

Partisan courts are not new. Most historians of the Supreme Court can identify times in U.S. history where the court acted on both sides of the political spectrum. Sometimes the results were good; other times, bad. But in all times where it went beyond its constitutional bounds, the process was corrupt.

Robert Bork, the eminent constitutional scholar whose 1987 nomination to the Supreme Court was rejected by the Senate, wrote extensively about the dangers of the court creating its own morality—whether it be conservative or liberal. He described the terrible scene of “massive marches,” “one by anti-abortionists and one by pro-abortionists,” coming down Constitution Avenue to the Supreme Court building to protest Roe v. Wade from his third-floor office window.

The demonstrators on both sides believe the issue to be moral, not legal. So far as they are concerned, however, the primary political branch of the government to which they must address their petitions is the Supreme Court. There is something very disturbing about those marches, for if the marches correctly perceive the reality, and I think it undeniable that they do, a major heresy has entered the American constitutional system.

A “major heresy” because, as Alexander Hamilton wrote and expected, “the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous” branch of government to the rights of the people. Hamilton was the primary author of the Federalist Papers, the incomparable exposition of the U.S. Constitution. Political philosopher Thomas Sowell said it could be titled Constitution for Dummies. Hamilton described in the Federalist Papers how the “least dangerous branch” could become a tyranny to fear:

It equally proves that though individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts of justice, the general liberty can never be endangered from that quarter: I mean so long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislature and executive; for I agree that “there is no liberty if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and the executive powers.” And it proves, in the last place, that as liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but it would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments.

Yet amid all the temptation the Supreme Court has been facing of late, highly respected law professors have called for future courts to not look to the restraints of the Constitution. Judge Richard Posner, a particularly influential scholar, said in an article on Slate that he saw “absolutely no value to a judge of spending decades, years, months, weeks, day, hours, minutes, or seconds studying the Constitution, the history of its enactment, its amendments, and its implementation.”

But as Robert Bork wrote, “the principles of the actual Constitution make the judge’s major moral choices for him. When he goes beyond such principles, he is at once adrift on an uncertain sea of moral argument.” To those judges who look outside the Constitution for guidelines, they can only look “inside himself and nowhere else.”

For those who would look to the courts to move forward legislation on affirmative action, immigration, abortion, gun control or any other polarizing issue, they are succumbing to a common temptation: trading the right of self-government for decisions from currently-benevolent judges. History has not been kind to those who went down that path.

But this trend is deeply rooted—and a trend the Trumpet has followed for a number of years. Trumpet executive editor Stephen Flurry wrote about what Judge Scalia’s death would mean for the Supreme Court in “Scalia’s Death and the ‘Living Constitution’”: The appointing of a judge who looks outside the Constitution for help will only lead to the erosion of the rule of law. And that is something that would have scared even Alexander Hamilton.