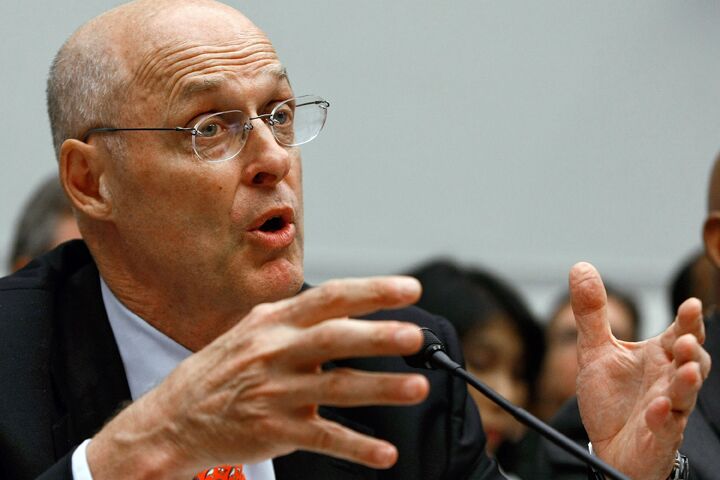

Henry Paulson’s Housing Fix—With Whose Money?

Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson is in trouble. The housing market is crashing and is threatening to take the whole economy with it. Over 2 million subprime mortgages with adjustable rates, taken out when rates were low, are set to ratchet up, and studies predict that more than half a million families could lose their homes. Worse yet for politicians, the crash is occurring against the backdrop of an approaching election year.

Attempting to contain the damage, Paulson says that the government and banks will soon agree on a plan to bail out subprime homeowners—and even better, he says, the plan “does not, and will not, include spending taxpayer money ….”

Sounds great, but just what is this magic plan? If taxpayers aren’t footing the bill, and banks and lenders are facing bankruptcy and have lost billions of dollars over the last quarter, where is the money going to come from?

Paulson explains.

“The number of subprime mortgage resets is going to increase dramatically next year, and we need to make sure the capacity is there to handle it,” Paulson said at a speech in Washington. Later, according to Bloomberg, he said that although the deal to rewrite the terms of a portion of subprime loans would “clearly” reduce the risks from the housing sag, it was not a “silver bullet.”

So far so good, but what needs to be done?

“The government has a role to play,” said Paulson, before stating that part of his plan is for state and local governments to help refinance subprime borrowers. “We are proposing to allow state and local governments to temporarily broaden their tax-exempt bond programs to include mortgage refinancing,” he said.

In other words, because so many subprime mortgage holders are not able to refinance their loans at rates they can afford (because of their credit score, income level, or because they bought homes they couldn’t afford), Paulson is suggesting that state and local governments sell bonds, the money from which would be used to refinance troubled homeowners’ loans.

Whoa. Hold on.

It may not be a free ride for taxpayers after all. Here is why.

If government housing authorities are given the go-ahead to issue low-cost mortgages to distressed homeowners looking to refinance, state and municipal authorities could end up holding hundreds of thousands of mortgages from subprime borrowers.

But there is a reason so many homeowners can’t afford to refinance: The market considers them too risky—and requires higher interest rates to compensate for extra risk.

Should the government risk taxpayer money on distressed subprime borrowers—without any extra compensation—especially when underlying property values are falling across the nation, and default rates among even borrowers with good credit ratings are rising? Government-sponsored housing lenders (i.e., taxpayer-sponsored lenders) could be left holding the bag.

This aspect of Paulson’s plan, while temporarily helping irresponsible borrowers keep their homes, does little more than shift the risk from banks and lenders to government-sponsored housing authorities, and therefore indirectly to taxpayers.

No free lunch here.

The irony in Paulson’s plan is also evident. Part of the reason so many people took out adjustable-rate mortgages in the first place was that they couldn’t afford to pay the high home prices with traditional mortgages. But one of the big factors contributing to home-price inflation in the first place was the fact that government-sponsored housing authorities began subsidizing first-time homeowners using tax-exempt bond programs, thus increasing the pool of home buyers and the demand for houses.

Someone always pays.

Full details of Paulson’s plan haven’t been released yet, so it is possible that banks and lenders will also be pressured to pick up part of the tab for bailing out underwater homeowners. But even if the banking and lending industry ends up footing a good chunk of the bailout (as they probably should since so many of them supported the unethical lending policies that are partially responsible for the current wave of foreclosures), taxpayers will lose in the end.

Banks don’t finance bailouts out of the goodness of their hearts. Besides giving them the chance to come out looking like heroes, you can be sure they will pass on the costs to their clients—everyday taxpayers like you and me. The Motley Fool Stock Advisor confirms:

They’re going to do it by firing employees. (Countrywide and Citigroup are already doing that.) They’re going to do it by moving offices to offshore tax havens, outsourcing, closing branches, lowering deposit rates, hiking fees, and whatever else it takes. …

Worst of all, they’re going to do it by soaking future borrowers—people like the majority of us, who didn’t do something stupid—with higher rates than we would have otherwise paid for mortgage loans, credit cards, and commercial loans. They’ll have to. They’ve got their own lenders to pay, and those lenders aren’t going to simply hand over-stretched Americans a pile of money.

As nice as it would be to get something from nothing, it just doesn’t happen in reality.

Taxpayers are certain to be affected if Paulson’s mortgage plan is implemented. “Without question, the … mortgage rescue plan will exacerbate, not alleviate, the problems in the housing market,” confirms analyst Peter Schiff. “As the plan will sharply reduce the ability of new buyers to make purchases, it really amounts to a stay of execution and not a pardon.”

If Paulson’s first plan doesn’t work, don’t worry—he has another up his sleeve. This second plan is a deal among America’s biggest banks, including Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and JP Morgan Chase & Co. The plan is to create an $80 billion fund to buy up the chunks of subprime mortgages and other asset-backed paper that nobody wants and that are threatening the financial integrity of America’s largest lenders.

It works something like this: America’s banks lent out billions of dollars to un-credit-worthy borrowers for overpriced houses. Now that the market has turned, and homeowners are defaulting on loans in droves and property values are plummeting, the banks are stuck holding billions in non-performing, rapidly devaluing assets. But the banks don’t have enough money on hand to cover their own potential loan losses. That’s why Paulson is encouraging banks to pool their money and create a fund to cover the loans.

The banks individually don’t have enough to cover positions, yet somehow if they pool their money they will? Talk about smoke and mirrors.

Investors certainly aren’t buying it.

Citigroup recently had to reach out to the oil-rich United Arab Emirates for a cash injection. Here’s the interesting part. It was so desperate that it was willing to pay 11 percent interest to get the money. That’s a loan-shark rate—for a bank! And America’s largest bank at that.

And while the treasury secretary was running around trying to implement a housing crisis fix, he also found time to reiterate his view that the economy was “fundamentally sound.” Paulson cited stable inflation, continued job gains, healthy company balance sheets and rising exports. Paulson also repeated his support for a “strong dollar.”

How someone with Paulson’s credentials (former ceo of influential banking giant Goldman Sachs) could say that he supports a “strong dollar” and simultaneously state that rising exports are responsible for the healthy economy, is amazing.

The biggest reason exports are rising is that the dollar has fallen by 16 percent since January.

And if Paulson thinks a plunging dollar, $90-per-barrel oil, $800-per-ounce gold, and near-record corn, wheat and milk prices are “stable inflation,” pity the average consumer who is experiencing the double-digit cost-of-living increase.

Concerning “healthy company balance sheets,” Paulson must not be referring to the banking sector. Citigroup, the biggest bank in the United States, reported a 57 percent drop in third-quarter earnings and said it would have to write-down a whopping $11 billion in mortgage-backed assets. Citi’s ceo Charles Prince promptly resigned. Bank of America, the second-largest U.S. bank, reported a 32 percent drop in earnings. The leading U.S. savings and loan, Washington Mutual, says it expects a 75 percent drop in profits, while Merrill Lynch had to write down $5.5 billion in bad subprime and leveraged-loan losses for June to September.

Then there are the “continued job gains” Paulson mentioned. Well-paying jobs don’t seem all that plentiful; gains at McDonald’s and kfc don’t qualify. Paulson must be thinking that the current housing market collapse will be different from all previous ones; otherwise, large job losses are most likely on the way. From the start of 2003 to March 2006, housing-related industries—including mortgage companies, homebuilders and contractors—contributed 23 percent of all new jobs. That translates to about 1.3 million, according to Moody’s Economy.com.

Reading between the lines, the economy is in big trouble and could be facing one of its biggest tests yet. The housing market is continuing to deteriorate, and quick fixes, no matter how successful, always come at a cost. There is no free lunch. Paulson knows that, but the demands of his office and politics must dictate that he not publicly acknowledge it.