Should You Trust Science?

According to the former editor of the British Medical Journal Richard Smith, it’s “time to assume that health research is fraudulent unless proved otherwise.” In an August 6 analysis piece posted on the British Medical Journal website, Smith reported that Ben Mol, professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Monash Health, had recently estimated that 20 percent of clinical trial results are fraudulent. Having been concerned about research fraud for over 40 years, Smith was unsurprised by Professor Mol’s view. “[I]t led me to think that the time may have come to stop assuming that research actually happened and is honestly reported, and assume that the research is fraudulent until there is some evidence to support it having happened and been honestly reported,” wrote Smith.

Smith and Mol aren’t the only scientists speaking out against research fraud. A small but growing segment of the scientific community has been alarmed by this trend for years. “It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines,” Marcia Angell, editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in 2009.

Richard Horton, editor in chief of United Kingdom-based medical journal the Lancet, wrote in 2015: “The case against science is straightforward: Much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue. Afflicted by studies with small sample sizes, tiny effects, invalid exploratory analyses, and flagrant conflicts of interest, together with an obsession for pursuing fashionable trends of dubious importance, science has taken a turn towards darkness.”

These are hardly the claims of crazed, wild-eyed conspiracy theorists. They are stern warnings from high-profile voices within the scientific community, backed by decades of experience—and a growing pile of evidence.

Consider this example from the British National Health Service:

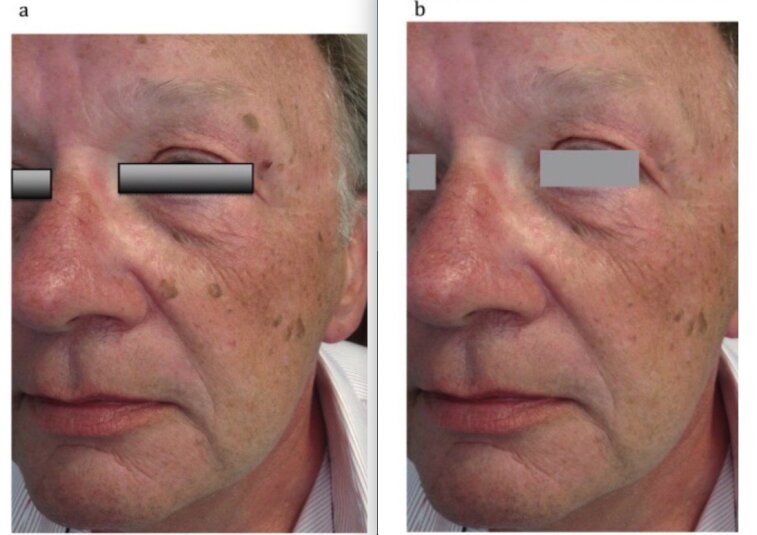

The images above come from a 2019 study conducted at an nhs hospital in Poole, UK. They supposedly show a patient before (left) and after (right) receiving laser treatment for keratosis. However, shortly after the study’s publication, a reader noticed that the photo on the right is actually a duplicate of the photo on the left—with the skin lesions photoshopped out. When confronted, the authors of the paper simply said, “The photograph was taken in the same room with a similar environment; unfortunately, the patient wore the same shirt.” However, after repeated harassment from whistleblowers on social media, the journal finally admitted that the photos had been airbrushed and retracted the paper.

Similar cases of fraud are being exposed with increasing frequency. In some cases, researchers merely play fast and loose with the facts, including data that support their hypotheses and excluding data that do not. A large number of medical papers have been exposed as complete fakes—containing detailed, technical descriptions of experiments that never happened, reams of made-up data, and photoshopped images.

Just last year, three bloggers exposed over 600 of these papers, tracing them to a single “paper mill” in northeastern China. After the exposé, a Chinese doctor involved in the scam contacted one of the bloggers, begging for mercy:

I kindly ask you to please leave us alone as soon as possible. Being as low as grains of dust of the world, countless junior doctors, including those younger than me, look down upon the act of faking papers. But the system in China is just like that, you can’t really fight against it. Without papers, you don’t get promotion; without a promotion, you can hardly feed your family. … You expose us but there are thousands of other people doing the same. As long as the system remains the same and the rules of the game remain the same, similar acts of faking data are for sure to go on. This time you exposed us, probably costing us our job. For the sake of Chinese doctors as a whole, especially for us young doctors, please be considerate. We really have no choice, please!

Remarkably, all 611 papers exposed by the bloggers had been translated and published in prominent Western medical journals, leading many to believe that the journals (or at least a few corrupt board members) may have been complicit in the scam.

It is somewhat unsurprising to find industrial-scale fakery in Communist China, but does similar fraud occur in the West?

A growing stack of evidence says yes.

Automated data-checking programs are one tool used to expose fraud. These computer programs scan thousands of scientific papers and recalculate their statistical conclusions (i.e. averages, standard deviations, p-values, etc). In other words, a data-checking program is to a scientific paper what a calculator is to a hand-written calculation. Though not 100 percent accurate, data-checking programs give a good estimate of how many scientific papers contain sloppy or fraudulent data.

Over the past decade, many of these programs have found a shockingly large number of mathematically impossible data points in medical literature. In 2015, researchers used the Statcheck program to scan over 250,000 p-values (a statistic used to measure the significance of observed data) in eight psychology journals. The engine found that “half of all published psychology papers … contained at least one p-value that was inconsistent with its test statistic ….” And an eighth of these papers contained a “grossly inconsistent p-value that may have affected the statistical conclusion.” In 2016, the grim program yielded similar results in a scan of 250 empirical psychology papers. Of those papers amenable to data-checking, half contained “at least one reported mean inconsistent with the reported sample sizes and scale characteristics,” and more than 20 percent contained multiple inconsistencies.

Outside of data-checking software, we know that scientists commit fraud because they themselves tell us. In a 2007 survey, 33 percent of scientists admitted to one or more of 10 unethical scientific practices, including plagiarism, making up data, and “cooking” existing data. Unsurprisingly, scientists are even more vocal when reporting their colleagues for fraud. Although surveys of this statistic have yielded widely diverging results, on average, the number of scientists who can recall instances of their colleagues committing fraud falls somewhere around 50 percent. One survey even put it as high as 92 percent.

The evidence backs Richard Smith and other whistleblowers in the scientific community: Medical literature should be assumed fraudulent until proved otherwise.

In “The Tyranny of ‘Science’ Falsely So Called,” Trumpet executive editor Stephen Flurry highlighted the extraordinary amount of faith our modern society puts in science:

The scientific community is probably the second-most-trusted institution in America, after the U.S. military. Only 20 percent of Americans say they trust the government, but 44 percent say they have a great deal of confidence in the scientific community. Faith in scientific experts has remained steady for the past 50 years— even after the drastic Fauci-recommended, government-enforced, covid-19 lockdown measures. …

In reality, science stands exposed as a false messiah.

Growing evidence of rampant fraud in medical literature exposes science for the false messiah that it is. Ironically, however, society is putting more trust in science—even as evidence piles up suggesting it should be doing the opposite.

To learn about the core problem with modern science and also its hope-filled solution, read Stephen Flurry’s article “The Tyranny of ‘Science’ Falsely So Called.”