Echoes of the 1930s

Germany has been shaken by an event with dramatic parallels with the 1930s.

In the late 1920s, the Nazi Party was small. In 1928, it won only 2.6 percent of the vote, hardly a force to be reckoned with. But the following year, in local elections in the German state of Thuringia, the Nazis won 11.3 percent. It wasn’t huge, but it was enough to make them kingmakers. Neither the mainstream-right parties nor the mainstream-left parties had enough votes to govern.

So the state went into coalition with the Nazis. Adolf Hitler’s friend Wilhelm Frick became the state’s interior minister.

The dam had burst. Less than a year later, Germany’s main right-wing party—the German National People’s Party (dnvp) worked with the Nazis to form a government in the state of Baunschweig. And by the end of 1932, the coalition was repeated at the national level, with Adolf Hitler as chancellor.

The rest is history.

After the Nazis took over Germany and started a world war that killed 60 million people, far-right parties were kept firmly out of coalition negotiations for 75 years. That is, until February 5 of this year.

Last October, the same state, Thuringia, held elections. Once again, neither the mainstream right nor the mainstream left received enough votes to govern alone. After months of coalition negotiations, once again, the mainstream right decided to compromise by asking the far right to help them form a government.

No wonder many Germans fear they’re walking down the same path as the 1930s.

“Democracies don’t die overnight,” warned Spiegel Online. “They don’t flourish one day and then get uprooted by a coup d’etat the next. They decay gradually, until the ground is fertile for an authoritarian seizure of power.

“[W]hat happened in Thuringia must be seen as a warning shot, a harbinger” (February 7).

Is German democracy on the way out?

Political Death Spiral

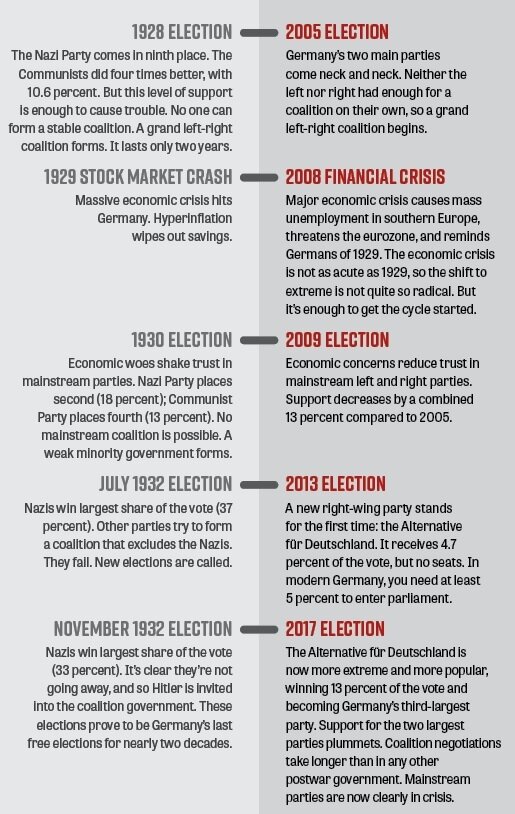

Thuringia is not the only parallel with the 1930s. The whole political dynamic in Germany and across Europe is the same.

Here is the pattern: An economic crisis hits, causing people to lose faith in the established parties. The mainstream consensus proves itself incapable, so a few people start to support more extreme parties.

This shift in support means mainstream parties can’t win a majority of votes. The mainstream right, for example, must either form a coalition with an extreme party or reach out to its opponent on the mainstream left.

Now the death spiral kicks in. A left-right coalition struggles. The two sides fundamentally disagree and cannot take bold action. They compromise with each other and form an unsatisfying centrist government. This causes more voters to reject the mainstream left and mainstream right and to vote for more extremist parties.

When extreme parties are brought into the government, they are normalized, given legitimacy. Voters grow likelier to vote for them. Either way, when the mainstream parties struggle, the fringe parties thrive.

This simply kicks the death spiral up a notch. It is now even harder to form stable coalitions. Governing becomes even less effective. Problems get worse. Support for the extreme parties grows.

This pattern played out in the 1930s, and it is playing out in Germany today.

In the ’30s, the spiral drove more and more voters toward the Nazis. By mid-1932, the dnvp decided that they had to work with Hitler, and offered him the post of vice-chancellor. Hitler refused, convinced he was powerful enough to demand the top job. This refusal led to another election, which the Nazis won. So German President Hindenburg invited Hitler to become chancellor. Frick, who had risen to power in Thuringia, now became the federal interior minister.

Hindenburg and the mainstream right believed they could “tame” Hitler. Instead, they empowered him. Once in position as chancellor, Hitler grabbed absolute power.

It is easy to see these parallels in Thuringia. In its October election, extreme parties gained most of the vote. Die Linke (The Left), successor to East Germany’s brutal Communist Party, won first with 31 percent. The Alternative für Deutschland won second with 23 percent. For any coalition to hold a majority in the state legislature, it must include one of these two parties.

New Right-Wing Party

The Alternative für Deutschland started in protest of the 2008 financial crisis. All the mainstream parties had roughly the same economic policy. The AfD was founded by economists to put forward an alternative path.

Then the migrant crisis hit Germany. Chancellor Angela Merkel welcomed a million migrants into Germany, with little debate or discussion. Those who had concerns were branded as racist by the mainstream media. So the AfD began offering an alternative view on migration as well.

This began a rightward shift that went far beyond merely concerns with migration. Björn Höcke, the leader of the AfD in the state of Thuringia, for example, wants a complete rewrite of German history. “German history is handled as rotten and made to look ridiculous,” he once told a rally. He wants a “180-degree reversal” on how Germany remembers World War ii.

To Höcke, the Holocaust memorial in Berlin is a “monument of shame” and should be removed. “The AfD is the last revolutionary, the last peaceful chance for our fatherland,” he said. He has even brought up “Lebensraum” (living space) and talked about Germany’s “thousand-year future,” clear allusions to Adolf Hitler’s expansionism and vision of a “thousand-year Reich.”

Concerned about the direction of their party, the original founders of the AfD left or were kicked out.

Not everyone in the party is as radical as Höcke. Some view him as more of a hindrance than a help; his extreme rhetoric makes it harder for the party to pick up more moderate voters, they complain. Nevertheless, he is still tolerated, and even promoted, as one of the senior leaders in the party.

With anti-Semitism surging worldwide, Jewish leaders are especially worried that politicians like Höcke are winning so many votes once again.

Charlotte Knobloch, former president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, said the AfD’s success “shows that our whole political system is coming apart at the seams.” She said she was worried that so many supported a party that has “downplayed the horrors of the Nazi era, who are openly nationalistic and have spread messages of hate against minorities, including the Jewish community.”

Christoph Heubner, vice president of the International Auschwitz Committee, sounded a similar warning, saying, “For survivors of German concentration camps, this massive increase in votes for the AfD in Thuringia is another menacing signal that right-wing extremist attitudes and tendencies are consolidating in Germany.”

“The last time we saw something of this kind in Germany was in the Weimar Republic where political life was polarized between the Communists and the National Socialists,” political scientist and commentator Werner Patzelt told the Local. “This is quite uncommon” (Oct. 28, 2019).

Some support the AfD due to legitimate concerns about migration. But it is not just their polling figures that parallel the 1930s. Their rhetoric does too.

Continent in Crisis

Fringe parties are rising all across Europe.

In Ireland’s February 9 general election, Sinn Fein—formerly the political wing of the ira terrorist group—tied for first place. Historically, Ireland’s mainstream parties have refused to work with them. Now they are stuck with a choice: form an unwieldy coalition or work with a group that has killed more civilians than al Qaeda did on 9/11.

Spain has held four inconclusive elections in the last four years. It currently has a coalition minority government, which is perhaps the most unstable arrangement possible. Meanwhile, a far-right party, Vox, has entered Spain’s legislature for the first time in its democratic history. In the November elections, Vox won third with 15 percent of the seats.

In 2010 and 2011, Belgium set a new world record for the longest period any developed country has been without a government: 589 days. Now the Belgians are going for a new record. Their last elections were on May 26, 2019, and they still don’t have a coalition.

Italian politics is dominated by parties that either did not exist before the 2008 financial crisis or were considered too extreme for government. In Sweden’s most recent election, its main left-wing party experienced its worst result since 2011, and the far-right Sweden Democrats are now, by some polls, the nation’s most popular party.

Eastern Europe is full of governments that are right wing, if not far-right, and most of these did well. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz won 52 percent of the vote, one of the only parties in Europe to win a majority. In Poland, the right-wing Law and Justice party garnered 45 percent of the vote.

In country after country, European politics are entering the same death spiral that many of them suffered in the 1930s.

During that fateful decade, the rise of the extreme parties didn’t happen only in Germany. The rise of extreme parties gummed up French politics. France had five governments between May 1932 and January 1934. In Austria, the death spiral empowered the Heimwehr—a far-right group similar to the Nazis but opposed to unification with Germany. In Czechoslovakia, the Nazi Sudeten German Party came from nowhere to win more votes than any other party. In Romania, the Iron Guard rose to become the third-most popular party, winning 15 percent of the vote in the 1937 elections, after having been banned in the 1935 elections. Other extreme parties, like the National-Christian Defense League in France, rose steadily after the 1929 stock market crash. France’s far-right Croix-de-Feu league grew from 500 members in 1928 to 400,000 in 1935. After it was banned in 1936, its leader started the French Social Party, which grew to become one of France’s largest right-wing parties. Votes for extreme parties in many other countries also jumped.

For all these people, a vote for the fringe wasn’t just a vote for a different political party. It was a vote for a different system. They didn’t want their current constitution or system of government. They were convinced their nation needed something different.

Many of the people voting for fringe groups today believe the same thing. Satisfaction with democracy is at an all-time low, according to a Cambridge study published in January. The report states, “Europe’s average level of satisfaction masks a large and growing divide within the Continent, between a ‘zone of despair’ across France and southern Europe, and a ‘zone of complacency’ across Western Germany, Scandinavia and the Netherlands.”

The Cambridge study traces the origin of this dissatisfaction to the economic crisis—just as was the case in the 1930s. It states, “It is likely that, beyond personal feelings of economic dissatisfaction, the crisis has brought forward a broader sense of political discontent that is tied to economic sovereignty, national pride, and anger over the use of public resources.”

In country after country, voters believe the political system no longer works for them. So they want someone different from the norm, someone outside the established parties. The way Europe has worked for decades isn’t working, they feel. They want something new.

Compromising With the Right

In the 1930s, the mainstream-right parties dealt with this rise in extremism by compromising with the right and moving further to the right themselves.

In 1931, Hugenberg’s manifesto called for the end of the Treaty of Versailles, the establishment of conscription, the reconquest of Germany’s colonies, a reduction in the number of Jews in public life, and stronger links with German communities outside of Germany. Politically, the difference between Hugenberg and Hitler was simply a matter of degree.

In France, far-right leagues succeeded in organizing violent protests. The more prominent right-wing parties responded by shifting their direction. These were among those that would make up the Vichy regime that cooperated with Hitler after he conquered their nation. In Romania, the king attempted to create a royal dictatorship to prevent Nazi-like parties from taking power in his country. In Hungary, the regent was forced to accept a far-right, anti-Semitic government.

Some in Germany are trying to respond to Thuringia the same way. Germany’s mainstream-right party is divided on the subject, but a substantial faction wants to shift the party to the right.

One leader of this faction, and a top contender to be Germany’s next chancellor, is Friedrich Merz. Foreign Policy explained, “Friedrich Merz would tack hard to the right, pushing the cdu toward the AfD in an attempt to recapture voters that have fled to the populist right in past elections” (February 11). It even speculated that Merz could bring the AfD into a coalition, taking the same course the mainstream right took in the 1930s.

Former Defense Minister Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg strongly endorsed Merz, telling the German Press Agency on January 17: “For me, there is only one politician in the [Christian Democratic] Union left, who I consider perfectly suitable for this task and who I would vote for: Friedrich Merz.”

Break With the Past

Recent events in Thuringia did not follow completely in the footsteps of the 1930s, however. The state leader elected with the help of the AfD lasted in office only one day. The outcry across the country forced him to step down.

Nor was he the only casualty. The fallout was so great it brought down Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Chancellor Merkel’s hand-picked successor.

Kramp-Karrenbauer came under attack for not stopping the deal with the far right. She was party leader—had she lost control of her own party? She was also accused of not speaking out forcefully enough against the AfD. Party members were already disappointed with her tenure as party leader. So she announced she would not stand as a candidate for Germany’s chancellor, and that she would resign as party leader, to be replaced in the summer.

This backlash was much stronger than the response to the Thuringia coalition in the 1930s. That history screams a warning so strong that Germany could not ignore it. The nation had to do something. So history from the ’30s is repeating itself, but not in exactly the same way.

The 1930s history remains a powerful warning for the future. Bible prophecy gives us an even more clear and specific warning. And that prophecy tells us there will be some major similarities—as well as some key differences from what has gone before.

Revelation 17 warns of a political system that rises and falls seven times. Verse 8 describes a beast, symbolic of a major world power, that “was, and is not, and yet is.” This beast exists, then vanishes—only to then “ascend out of the bottomless pit.” You could say it comes out of nowhere—from “underground.”

This chapter describes it as having seven heads: It rises seven times. Verses 1-2 tell us it is led by a woman, the biblical symbol for a church.

Where in the world is there an empire, led by a church, that repeatedly rises and falls? This passage can only be referring to the Holy Roman Empire in Europe, a series of empires that have all attempted to resurrect the Roman Empire, and that have all been dominated by the Catholic Church.

This power has risen and fallen six times so far. Revelation 17 says that when this power fully ascends, “the people who belong to this world … will be amazed at the reappearance of this beast” (verse 8; New Living Translation). They believe this beast is dead, but then it comes back one more time.

We are seeing that beast power rise in Europe one more time.

Because this is the same beast that rose in the 1930s, there are some critical parallels. But the seventh and final resurrection of this empire is unique. The book of Daniel has a series of prophecies describing the rise of the man who will lead this empire.

A Coming Strongman

Daniel wrote his prophetic book for the end time (Daniel 12:9). It prophesies events that have now happened; they were prophecy for him, but now history for us. But even these historical events are types of what is still ahead of us.

Daniel 8:23 describes the rise of “a king of fierce countenance, and understanding dark sentences.” Verse 25 says he will be defeated after he stands up “against the Prince of princes,” revealing the time frame for this fierce king’s reign: He will come to power in the very end time, right before Jesus Christ’s Second Coming. Revelation 17 also describes the beast power and its leader fighting Jesus Christ. The Daniel 8 man leads the beast described in the book of Revelation.

Another passage in the same prophetic book—Daniel 11:21-31—tells us how this man will come to power.

Most Bible commentaries correctly say this passage refers to Antiochus Epiphanes, who reigned around 175 to 164 b.c. These verses forecast exactly what Antiochus ended up doing. They prophesied that he would “pollute the sanctuary of strength, and shall take away the daily sacrifice, and they shall place the abomination that maketh desolate” (verse 31). Antiochus infamously assaulted and slaughtered the Jews and attacked the Jewish religion. He attempted to stamp out Jewish worship at the temple and set up a pagan statue to Jupiter Olympius in front of the altar.

In Matthew 24:15, Jesus Christ clearly refers to this verse, making explicit reference to “the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet.” But He talks about it not as something that had already happened, but as something that will happen in the future.

If this prophecy was entirely fulfilled by Antiochus Epiphanes nearly two centuries earlier, why did Christ tell His disciples to watch for this event? This prophecy had an ancient fulfillment, but it will also have a modern one. Like many other prophecies, it is dual. This refers both to the ancient Antiochus and to a modern Antiochus.

Daniel 11:21 prophesies that the European people “shall not give” this Antiochus “the honour of the kingdom: but he shall come in peaceably, and obtain the kingdom by flatteries.” The Jamieson, Fausset and Brown Commentary says that “the nation shall not, by a public act, confer the kingdom on him, but he shall obtain it by artifice, ‘flattering.’” Barnes’ Notes on the Old and New Testaments states, “[I]n other words, it should not be conferred on him by any law or act of the nation, or in any regular succession or claim.”

Look at Germany right now. In your lifetime, have Germans ever been more worried about their political situation? They see that they are sliding down the same path as the 1930s. They see that they are beset by potential crises, with another episode of the migrant crisis or the euro crisis likely to break out at any time. Yet at the helm are two lame ducks.

With Germans desperate for a strong leader, and none on the horizon, circumstances are almost perfect for someone to come into power in an unorthodox way. What happens if there is some kind of crisis between now and summer, and Ms. Merkel is forced to step down? If politics as usual cannot give the already-restless Germans the leader they need, what can they do?

In the Trumpet’s January cover article, editor in chief Gerald Flurry showed just how many specifics the Bible gives us about this coming strongman. He explained that this strongman “will somehow manipulate the political system to effectively hijack Germany and, by extension, Europe.”

“Knowing that such political intrigue will occur makes the bureaucratic turmoil in Berlin important to watch,” he wrote. “The government is shaky, the need for strong leadership is clear—but the path to achieve it is unknown.”

Daniel 8:23 says this leader is known for “understanding dark sentences.” The expression “dark sentences” means that he operates “at a higher social level.” Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon defines this phrase as “twisted, involved, subtlety, fraud, enigma.”

“This is revealing insight,” wrote Mr. Flurry. “The prophesied strongman operates on a high social level; he is capable of understanding and solving complex issues and questions. He is brilliant and sophisticated, and he has intellectual depth and power. The context shows he enjoys notoriety and fame for it.”

“This prophesied leader may well exploit this frustration and confusion by rallying a coalition behind him and vaunting himself to power,” he continued. “This would take a lot of intelligence and calculation; it would require unusual skill to deceive people in high places with flattery. But the prophesied Daniel 8 man will do it magnificently. Adolf Hitler was a man of mental strength, but he was not as adept at deceiving people as this coming strongman will be! This leader will come as an angel of light.”

The stage is perfectly set for the rise of this man. Europe is treading the same path that led to a dictator before, and it will get a dictator once again.

But the Bible records one other important difference between this time and the 1930s. When Hitler was defeated, his empire went underground, to rise again later. This time, the empire will not go underground. Daniel 8:25 says that this strongman will “stand up against the Prince of princes.” He will try to fight Jesus Christ when He returns, “but he shall be broken without hand.”

This whole system, that has caused wars for hundreds of years, will be destroyed forever. And it will never be resurrected again.