Will China Rule the Waves?

Money makes the world go round. And that money often flows through maritime passageways.

These passages seem remote and uninteresting. Yet they affect our lives in very direct ways.

Ninety percent of the world’s trade travels by sea. In the United Kingdom, 95 percent of the products we use come from overseas, according to the Maritime Foundation. Electronic devices, clothing, raw materials and so many other things come to us via ships.

Shipping provides not only products but the literal lifelines of modern nations. Most of the UK’s food comes from overseas. Oceangoing tankers carry 60 percent of the world’s oil.

Most maritime trade travels through narrow waterways that the Trumpet often refers to as sea-gates.

About one third of all oceangoing trade sails through the South China Sea, within range of weapons China has stationed on its newly fortified islands. Thirty-five percent of all oceangoing oil exports sail through the Strait of Hormuz, a waterway controlled by Iran. A quarter of all oceangoing oil sails through the Strait of Malacca, just northeast of Singapore. Around 10 percent of that oil goes around the southern tip of Africa. About 15 percent of the world’s maritime trade travels through the Red Sea. Five percent of it goes through the Panama Canal.

Our everyday lives depend on a constant flow of materials and goods from overseas. And this flow depends on free passage through sea-gates. Close these gates using warships, warplanes, mines, shipwrecks or other means, and the oil market will panic, global economic chaos will result, and the UK will quickly begin to starve.

“Disruptions to global supply chains are, in fact, more devastating than a traditional military attack,” wrote Elisabeth Braw in Foreign Policy. She warned that even a cyberattack on a port or shipping facility could be deadly. “An adversary could bring a country to its knees without dispatching a single soldier,” she wrote (August 7).

Which is why sea-gates and empire—or even sea-gates and world domination—often go hand in hand.

A new power is quickly moving to take control of sea-gates. The history of these gates shows the importance of its moves.

The Gates of Empires

The first truly global empire was the Portuguese Empire. And it was an empire of sea-gates. Vasco da Gama returned in 1499 from his discovery of a sea route to India. Just six years later, Portugal was thinking about sea-gates. In 1505, one Portuguese explorer wrote that there was “nothing more important for the country than to have a castle at the mouth of the Red Sea, or very near to it.”

Which is exactly what the Portuguese did. In 1507, they captured an island near the Bab el-Mandeb and built a fort.

The key sea-gates of the East fell with dizzying speed. Portugal established a base in India in 1510. It captured the Strait of Malacca in 1511, Hormuz in 1515, and built a fort in Sri Lanka in 1518. It failed to control the Red Sea and was quickly kicked out of its Bab el-Mandeb base. Nonetheless, its dominance of sea-gates made it one of the world’s most powerful empires. By 1571, Portugal controlled 40 forts or trading posts.

But competition was not far behind.

The Dutch Empire began as an economic enterprise: the Dutch East India Company. It aimed to make a profit trading with the East Indies, though it was authorized to set up “fortresses and strongholds” and employ military personnel.

The merchants certainly needed strongholds. The Dutch had been at war with Spain for most of the second half of the 16th century. In 1580, Spain absorbed Portugal—meaning the Dutch were now also at war with Portugal. Portuguese forts and trading posts became a prime target for the Dutch.

The Dutch East India Company captured Jakarta in 1619. It established a colony in Taiwan in 1624. The Strait of Malacca fell in 1641, and the Portuguese were driven out of Sri Lanka by 1658.

England had its own East India Company. The company initially set up trading posts rather than forts. By 1647, it had 23 of them. But trading posts need protection, and England was at war—with Spain at first and later with the Dutch and French. The major trading posts became forts: The first was completed in 1644.

England also fought back against rivals over sea-gates. In 1622, the English and Persians attacked Hormuz, opening the strait and allowing England to trade with Persia.

England ended up pushing the Dutch out of India while the Dutch held on to Indonesia. England captured Colombo in Sri Lanka in 1796. The Dutch handed Malacca over to Britain in 1824.

At the same time, Britain was capturing other gates. It took Gibraltar in 1704. It occupied Egypt in 1882, gaining control of both ends of the Mediterranean.

“At the peak of its imperial power around 1900, Great Britain ruled the waves with a fleet of 300 capital ships and 30 naval bastions—fortified bases that ringed the world island from the North Atlantic at Scapa Flow off Scotland through the Mediterranean at Malta and Suez to Bombay, Singapore and Hong Kong,” writes Alfred W. McCoy in his book In the Shadows of the American Century. “Just as the Roman Empire had once enclosed the Mediterranean, making it mare nostrum (‘our sea’), so British power would make the Indian Ocean its own ‘closed sea,’ securing its flanks with army forts along India’s northwest frontier and barring both Persians and Ottomans from building naval bases on the Persian Gulf.”

But others wanted a piece of the action. Germany especially wanted colonies; it especially wanted overseas bases near key sea passages.

The Germans were far behind in setting up naval bases, and they were reluctant to openly challenge the established powers until they were ready. They particularly desired a base in East Asia. In 1897, two German Catholic priests were killed in China. The local German naval commander sent a telegram home: “May incidents be exploited in pursuit of further goals?” he asked. Kaiser Wilhelm ii’s answer was, Yes, they could. Germany attacked Jiaozhu Bay, announcing a temporary occupation. The next year, a treaty with China extended that to a 99-year lease.

Germany also wanted a naval base in Latin America. Germany had strong commercial links with Latin America, which it wanted to protect. German cabinet papers show that the Kaiser and others hoped to one day attack the United States, and they needed a base to launch it from.

Venezuela owed Germany (and Britain) a lot of money, and in 1902 it refused to pay it back. Normally, America would refuse to allow an attack on a Latin American state by a European power. But United States President Theodore Roosevelt declared, “If any South American country misbehaves toward any European country, let the European country spank it!”

However, Germany told Britain that as part of this spanking, it was considering “the temporary occupation on our part of different Venezuelan harbor places.” Roosevelt feared that this “temporary occupation” could turn into another 99-year lease, so he put a stop to the German attack.

This German plan to take a sea-gate failed. But the strategy is instructive. It shows how a nation that wants more of these sea-gates may try to acquire them without angering an established power.

Meanwhile, the United States controlled the Gulf of Mexico, built the Panama Canal, and sent its Navy and other military forces around the world, starting with Cuba and the Philippines. Cuba cemented America’s control over the Caribbean, and the Philippines extended its control across the Pacific. World War ii spurred America to station forces in hundreds of overseas bases, often near key choke points. The rise of the American empire coincided with its domination of global sea-gates.

Today, there is a new power on the block. This power is steadily moving in on ports and sea-gates around the world, especially in East Asia.

This power is China. Will it be the next global empire?

The Rise of China

Take Sri Lanka, an island whose harbors passed from the Portuguese to the Dutch to the English. Since 2005, China has invested $15 billion into Sri Lankan infrastructure. And it has received a good return on that investment. Sri Lanka borrowed $1 billion to improve the key Port of Hambantota. It is the headquarters of the Sri Lankan Navy and, after the investment, a modern port.

But like Venezuela, Sri Lanka couldn’t repay the loan. In December 2017, China took control of the port. Now China runs it—on a 99-year lease. “That port then gives them not only a strategic access point into India’s sphere of influence through which China can deploy its naval forces, but it also gives China an advantageous position to export its goods into India’s economic sphere, so it’s achieved a number of strategic aims in that regard,” Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told cnn. This is “part of a determined strategy by China to extend its influence across the Indian Ocean at the expense of India,” and it’s using Sri Lanka to achieve its ambition (February 18).

Now experts think that Djibouti could be next. The country sits on the Bab el-Mandeb—the same vital sea-gate that the Portuguese and Ottomans fought over 500 years ago. Djibouti has debts equal to about 90 percent of its economy. Much of that debt is owed to China. Which is why Foreign Policy asked, “Will Djibouti Become Latest Country to Fall Into China’s Debt Trap?”

“As Chinese President Xi Jinping continues to push lending to developing countries, policy analysts are sounding alarm bells about the fate of smaller nations biting off more than they can chew—and the strategic possibilities opening to China as a result,” Foreign Policy wrote (July 31).

Djibouti is the site of China’s first overseas military base. It is also home to Camp Lemonnier, America’s only permanent base in Africa. Foreign Policy noted, “One concern is that the Djiboutian government, facing mounting debt and increasing dependence on extracting rents, would be pressured to hand over control of Camp Lemonnier to China” (ibid).

The port of Gwadar in Pakistan is all but a Chinese military base. Since 2011, China has poured in almost $250 million to transform a fishing village into a key deep-water port. It is pouring in another $46 billion to create a China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

The vast majority of China’s current projects are nonmilitary. China is expressly forbidden from militarizing the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, for example. However, Gwadar shows how quickly it can change. With the port built up, Pakistan opened a naval base there. China kindly donated two warships. And Pakistan quickly noted that China was welcome to base its own military ships there too. Then, in January this year China made it official, announcing that it would build its second overseas military base in Gwadar.

With many of these countries still getting deeper and deeper into debt to China, it’s easy to see how they too could be forced to allow in the Chinese military. And as hundreds of years of history have shown, where traders travel, the military always follows to protect these key national interests.

One of China’s most important sea-gates is the Strait of Malacca. About 80 percent of China’s energy imports come through this 2-mile-wide waterway. In 2016, China announced plans to develop a major deep-sea port in the strait that could compete with Singapore.

The Maldives includes a strategic sea base that passed from the Portuguese to the Dutch to the British. And now the Chinese could be next. China has “expressed interest in building a port in the Maldives,” according to the South China Morning Post (March 22). The Maldives has allowed Chinese ships to dock. And it owes almost three quarters of its foreign debt to China.

At the far end of the ocean is another sea-gate that could be falling into Chinese hands: Vanuatu. China has helped to build the nation’s parliament building and the prime minister’s offices. It is working on new official residences for the president, the Finance Ministry building and extensions to the Foreign Ministry building. It has given Vanuatu loans of over $100 million to build a wharf.

No wonder the Australian press sounded the alarm bells in April over reports of “preliminary discussions” between China and Vanuatu about “building a permanent military presence in the South Pacific in a globally significant move that could see the rising superpower sail warships on Australia’s doorstep,” as Fairfax Media put it (April 9). China and Vanuatu both strenuously denied the reports. But it’s a well-founded fear, given how much of Vanuatu is already in China’s pocket and what China has done in similar situations elsewhere.

But China’s reach isn’t confined to the west Pacific and Indian Ocean.

America’s Backyard

The Panama Canal is America’s most important sea-gate. Not only do huge amounts of U.S. commerce travel through it, but it allows the U.S. Navy to pivot its fleets quickly from the Pacific to the Atlantic and back.

China has full control of the ports at both ends of the canal. The Chinese company Landbridge has bought Panama’s largest port. In October 2017, China Habor Engineering Company began work on a cruise ship port.

“The rate at which China is acquiring and establishing these commercial bases [in Latin America], they can easily turn a nonmilitary base into a usable, military one,” Evan Ellis, a professor of Latin American Studies at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, warned in 2017 (emphasis added).

China is also investing in Brazil’s ports. The Guardian called the Superporto do Açu “one of the most visible symbols of China’s rapidly accelerating drive” into Latin America (Sept. 15, 2010). China also owns a 51 percent stake in a new port being built in São Luis in northeastern Brazil.

China has employed a similar strategy in Europe, where it has used the European debt crisis to go on a massive shopping spree. Piraeus is Greece’s largest port. A deep harbor close to the Suez Canal, it is a key stopping point for international shipping. China’s cosco holds a 70 percent stake in the port. It also has a controlling stake in Spain’s container terminal operator Noatum Port Holdings. In addition, China operates the port of Venice, which it aims to transform into a hub of international trade. cosco also has complete control of Zeebrugge in Belgium, the world’s largest car-handling port.

A Chinese Lake

And none of this takes into account the massive Chinese presence in the South China Sea. With a series of artificial islands and long-range missiles, the Pentagon has warned that China is turning the area into a “Chinese lake.”

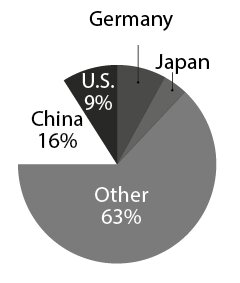

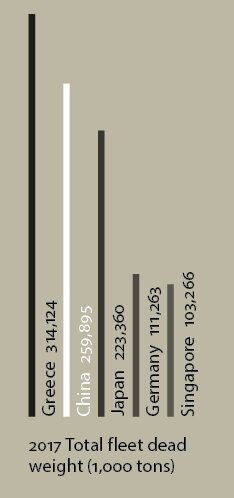

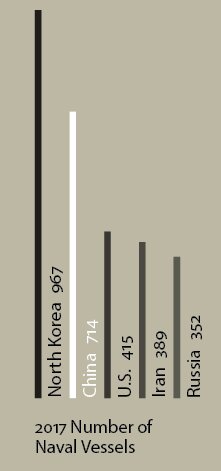

China completed its first domestically manufactured aircraft carrier this year, and it has a bigger one in the works. It has been churning out around a dozen large naval ships a year. It aims to produce three of its impressive new destroyers each year.

In just five years, China “will complete its transition” into a modern navy capable of “sustained blue water operations” and “multiple missions around the world,” according to the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence.

By 2030, China’s navy is estimated to be almost double the size of the U.S. active Navy. Those ships may not be of the same quality, but China is catching up quickly there as well.

U.S. Vice Adm. Thomas Rowden has warned of “a new age of sea power.” “From Europe to Asia, history is replete with nations that rose to global power only to cede it back through lack of sea power,” he warns.

A Serious Threat

China, then, is on the path toward riches and global dominance. It is a path many others have taken before; most recently, by the United States.

America’s riches and dominance are a massive confirmation of Bible prophecy. And the Bible has a lot to say about how China’s efforts will turn out.

In Genesis 22:16-18, God told Abraham that He would multiply his descendants “as the stars of the heaven, and as the sand which is upon the sea shore.” These descendants, He said, would “possess the gate of his enemies.” Rebekah, Abraham’s daughter-in-law, was told “be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them” (Genesis 24:60). What, in the context of “thousands of millions” of people, could the Bible be talking about? What gates affect millions of people? What is the closest thing international relations has to a gate?

This has to be about sea-gates.

The Bible says that one people would dominate the world’s maritime passageways. And this is exactly what we saw happen.

But the Bible also prophesies that Britain and America will lose these gates. In Deuteronomy 28:52, God tells the recipients of these blessings that if they fall away, they will be besieged “in all thy gates.” The gates they once owned will be slammed shut.

Britain has already given up nearly all of its gates. The U.S. has given up the Panama Canal, and it is watching its grip slipping around the world as other nations win control of these gates.

The Bible also indicates that China will be doing a lot of the slamming.

Isaiah 23 talks of a maritime alliance between China (biblical Chittim) and Europe. “Considering that China now possesses most of the world’s strategic sea-gates (at one time held by Britain and America), the German-led Holy Roman Empire will need to form a brief alliance with the Asian powers identified in Isaiah 23 (Russia, China, Japan—the ‘kings of the east’),” wrote editor in chief Gerald Flurry in the July 2016 Trumpet issue.

That is a sobering forecast, once you realize how vital these gates are. But at the same time, this understanding makes the Bible come alive as you watch world news.

Watching sea-gates helps confirm that the Bible is a now book. It describes the world we live in, and it discusses real-world problems. Most of all, it shows that the bad news we see around us is just part of a positive and inspiring plan.

You can learn more about this plan in our free book The United States and Britain in Prophecy, by Herbert W. Armstrong. As he wrote, this book contains “the strongest proof of the very active existence of the living Creator.”