How Cheap Gas Is Changing the World

Pulling up to a pump is almost a joy these days. For 113 consecutive sunshiny days, prices at the gasoline pump have fallen. For the past nine months, it has been almost nothing but blue sky and daffodils. In 18 states in the United States, sub-$2-per-gallon gas is igniting smiles and optimism not experienced since the 2008 economic crash.

For a typical family, lower gasoline prices mean an extra $1,150 per year to spend on, well, whatever the heart desires, according to Citigroup analysts. With 115 million households in the U.S., that is a lot of extra coin to go around.

The extra cash is an immediate boost for the American economy. And that is making a lot of people happy. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that U.S. gross domestic product grew at a barn-burning 5 percent rate during the fourth quarter of 2014—the fastest growth since the economic crash in 2008.

Yet not all is sunshine and flowers. Yes, the extra money in your wallet is nice—but you need to understand the dramatic problems this trend is creating throughout the world around you.

American Economy

For starters, all these happy motorists are tooling around in an American economy under threat from risks that did not exist just a few years ago. Big ones.

You may not realize this, but in the years following the 2008 Wall Street meltdown, shale oil revolutionized America’s economy. And last year, according to Bank of America analysts, the U.S. overtook both Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s largest oil producer.

Shocked? Didn’t realize that America was the world’s biggest oil bigwig?

How is this possible? Fracking technology. This new tech, developed and pioneered in the U.S., allows companies to extract oil from rock. It also releases natural gas, which America became the world’s largest producer of in 2010.

Massive amounts of previously inaccessible energy helped power America’s economy after the 2008 crisis. The shale oil and gas revolution has been the nation’s biggest single creator of full-time, middle-class jobs since the 2008 economic crash. As economic analyst John Mauldin pointed out, nearly 1 million Americans work directly in the oil and gas industry, along with another 10 million indirectly.

“The important takeaway is that, without new energy production, post-recession U.S. growth would have looked more like Europe’s—tepid, to say the least. Job growth would have barely budged over the last five years,” Mauldin wrote (Mauldin Economics, Dec. 16, 2014).

But America’s energy boom was predicated on oil prices that no longer exist.

The average mid-cycle break-even price of a shale oil company operating in the North Dakota’s Bakken field is $69 per barrel, according to Scotiabank analysts. The break-even cost in the Permian Basin in Texas comes in at $68 per barrel; the Niobrara, $59; the Eagle-Ford, $50.

Remember, these are mid-cycle break-even prices that don’t factor in the upfront costs of acquiring land and infrastructure. You need to tack on $5 to $10 more per barrel for those costs.

Today, nobody wants to pay more than $45 per barrel.

Houston, we have a problem.

The vast majority of America’s newest oil production—the production that has powered so much of America’s recent job growth—is uneconomical at current prices. Existing oil wells will continue to be pumped because companies have no other choice, but if prices remain low for more than a few months, future development will grind to a halt. Well permit applications were down 40 percent in November and did not recover in December. Layoffs at exploration and production companies are starting too.

Making matters worse, America’s oil boom was financed by extreme debt. This may be the bigger danger for America.

“The reality is that the recent energy boom was financed by $500 billion of credit extended to mostly ‘subprime’ oil companies, who issued what are politely termed high-yield bonds—to the point that 20 percent of the high-yield market is now energy-production-related,” wrote Mauldin (ibid). “High yield” bonds is code for junk bonds.

We may be cruising straight into a “subprime” oil crisis. If so, shale oil companies and the banks that lent to them will be the first to be totaled. Your 401(k) or pension plan will get smashed next. And individuals and businesses throughout the economy will pile up one after another.

“Losses are going to cascade through the system,” former cia financial analyst Jim Rickards told RT. “There are unforeseen consequences and hidden losses. I am not so sanguine that this is going to work out so smoothly in the end …. This looks like the beginning of [a crisis].”

These wild swerves in the price of oil have real-world effects on national economies. Everyone in the sector—and a lot of people driving along nearby—is about to take some damage.

North and South of the Border

In Canada and Mexico, two more major oil-exporting nations, cheaper oil is also a mixed blessing.

In Canada, the oil sands have among the highest all-in-cost of production—even higher than U.S. shale oil. The advantage Canada has is that oil sands operations are conducted more like mining operations: Once the mines get built, they produce the oil relatively inexpensively for up to 30 years or more. So even with low prices, it’s still profitable to keep the oil flowing to market. However, new projects will be put on hold. In contrast, shale oil wells produce about 90 percent of their oil their first year and run dry after three years. So if oil prices don’t improve quickly, these U.S.-based competitors will be the first to go bust.

Oil-producing provinces like Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland will be hit hardest. Provincial collections will be smaller than expected.

On a federal level, the value of the Canadian dollar is falling with the price of oil. This will give a short-term boost to the manufacturing export sector. Ontario, a large oil consumer and home to Canada’s industrial heartland, will benefit from low oil prices the most. Since the U.S. economy is more diversified, the U.S. dollar is not falling with the oil price. The relatively stronger U.S. dollar will make Canadian-manufactured goods cheaper than domestically produced ones. American manufacturers will lose market shares and jobs.

In Mexico, the low oil price could hit with a devastating punch. The energy sector accounts for a full 13 percent of Mexico’s economy. Much of Mexico’s oil production is Gulf oil, which comes from aging oil fields and is costly to produce. The longer prices stay low, the greater the threat that these fields will become uneconomical. Additionally, oil accounts for 32 percent of government revenue, and the Mexican government has based its 2015 budget on an average of $79 a barrel. Mexicans are going to lose some jobs as well as government spending. This could lead to more social instability.

But as important as oil is to North America, taken together, Canada, Mexico and the U.S. are not only close to energy-self-sufficient, but they are also close allies. The same cannot be said about the rest of the world. Plunging oil prices, while an economic blessing to some nations, threaten to collapse others.

Falling oil prices might even mean war.

Here is a summary of the most important considerations from several oil-related tension points around the world.

English-Speaking Ally in Europe

The United Kingdom’s North Sea oil fields, once the envy of the world, are “close to collapse,” Robin Allan, chairman of the independent explorers’ association Brindex, told the bbc in December—when oil was still in the mid-$60s.

The North Sea oil fields are especially vulnerable because they are old and expensive to develop. Production peaked in 1999 and has since fallen sharply. According to Allen, no new projects in the North Sea are profitable with oil below $60 per barrel. “It’s a huge crisis,” he said.

It may be a crisis in terms of jobs, employment and revenue—but from a geopolitical perspective, it has the potential to be a total disaster.

North Sea oil made Britain energy self-sufficient. Until 2007, it was not reliant on other nations for its energy supply. Since then, Britain has had to import increasing amounts of oil and gas.

In a world of sub-$60 oil, the UK could soon come to rely heavily on imported fuel. And the list of fuel suppliers ranges from unsavory to outright hostile.

But while Britain faces the loss of its oil supply, other nations are slip-sliding to happy days and big bank accounts.

The Biggest Winner Is?

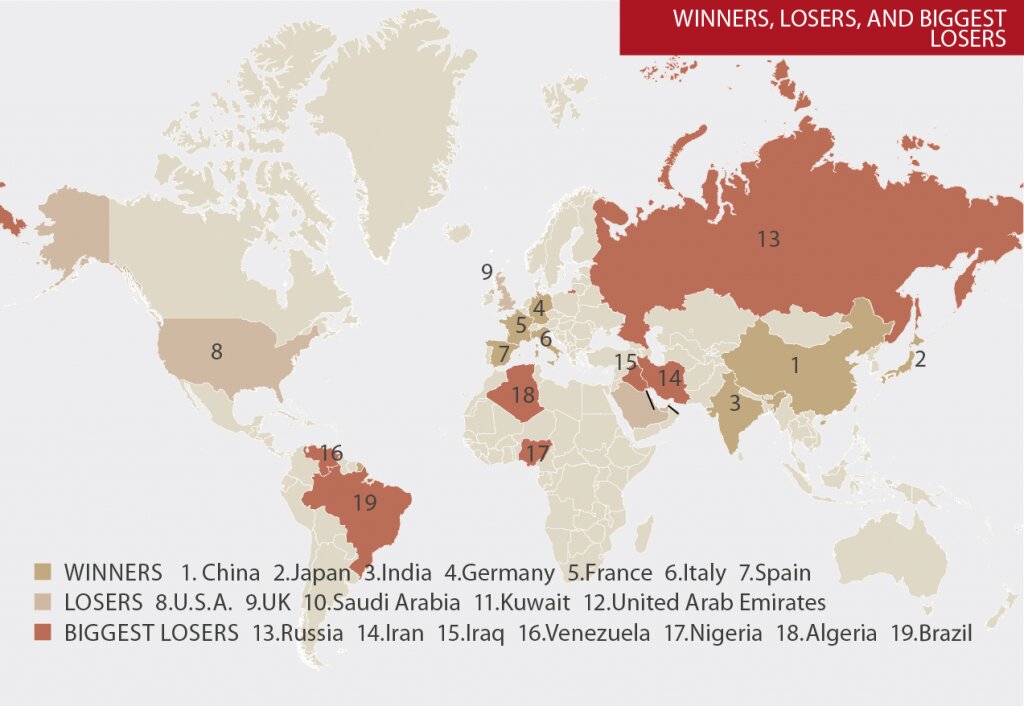

For every dollar the price of oil falls, China saves $2.1 billion per year. Do the math. That is a $200 billion-per-year boost to China’s economy, courtesy of oil falling from $140 per barrel. This massive economic stimulus could hardly have come at a better time.

The lower price of oil and gas also gave China the additional leverage it needed to finalize two massive pipeline deals with Russia. Worth close to $800 billion and characterized as the biggest pipeline construction projects in history, these lines will soon make Russia into China’s most important energy supplier.

So China gets the world’s biggest oil-price subsidy and decades’ worth of oil and gas delivered right to its doorstep.

Second place goes to the Europeans. Continental Europe imports 70 percent of its oil and gas supplies. Again, lower fuel costs equals an economic boost. With many countries locked in recession, lower petrol prices are a welcome respite.

But it will be temporary relief. Much of Europe’s oil and gas comes from Russia, and as we will see, that means trouble.

The Biggest Loser Is?

You can’t discuss oil prices without considering the world’s premier oil cartel. And it is a cartel in chaos.

Saudi Arabia’s powerful oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, made a shocking comment on December 22. He told the Middle East Economic Survey that it was “not in the interest of opec producers to cut their production, whatever the price is” (emphasis added). “Whether it goes down to $20 a barrel, $40, $50, $60, it is irrelevant,” he said.

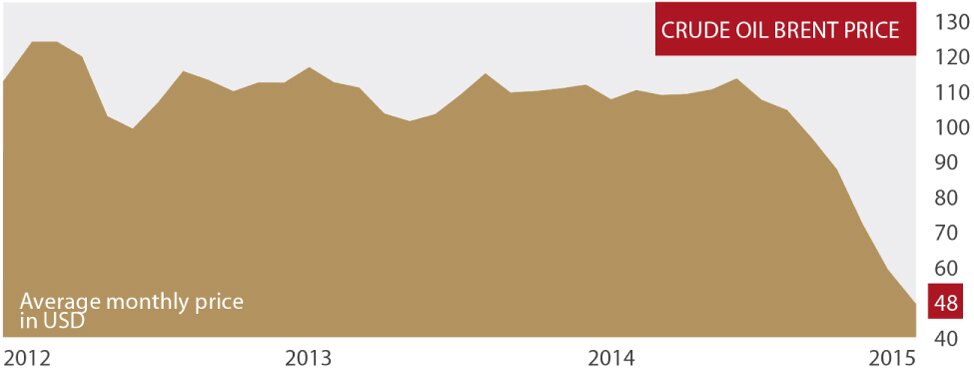

His odd comments came as the price of oil hits multiyear lows. Since June, U.S. crude has cascaded from $107 per barrel to $44 per barrel. The sell-off in Brent crude, the oil purchased by Europe and Asia, is even steeper. It has plummeted from $112 per barrel to $46. Just a few years ago, oil traded for $140 per barrel.

It is the second-sharpest decline in history, yet the Saudis seem to want it to go even lower. This is strange because the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (opec) cartel was founded to do just the opposite—keep oil prices high by limiting supply.

So what are the Saudis up to?

For several opec member nations, oil is a matter of life and death. The International Monetary Fund in October analyzed the oil prices various governments need to balance their budgets. The nations on the Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar) can survive with $70-per-barrel oil. These nations also tend to be the ones with the largest financial reserves. According to one estimate, Saudi Arabia could survive for two years at current prices with minor difficulty. These low-cost opec producers may even benefit in the longer term from lower oil prices.

Depressed prices shake out the competition. If oil prices stay low long enough, production from old, less profitable fields and new, expensive fields may be shuttered. Once closed, the costs to reopen can require much higher oil prices to be economical. Additionally, low oil prices will begin to suppress alternative energy sources as well. When companies go bankrupt, plants and equipment get neglected, supply chains break down, and it becomes more difficult for industries to start back up again.

Some analysts have speculated that the Saudis’ desire to drive prices lower was targeted at U.S. fracking companies, which are responsible for almost the entire increase in global oil production over the past five years. On November 3, the Wall Street Journal quoted Saudi sources saying they would sell oil to America for less than their Asian customers pay. So it is possible that U.S. production was a target, but it is more likely the sheiks had other targets in their sights.

Consider which opec nations are the big losers.

“Saudi Arabia, U.A.E. and Qatar can live with relatively lower oil prices for a while, but this isn’t the case for Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela, Algeria and Angola,” said Marie-Claire Aoun, director of the energy center at the Institute for International Relations in Paris. “Strong demographic pressure is feeding their energy and budgetary requirements. The price of crude is paramount for their economies because they have failed to diversify” (Bloomberg, Dec. 1, 2014).

Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela, Algeria, Angola and Libya are all considered Iran’s opec allies. And bitter enemies of the Saudis. These nations all need $100-per-barrel oil or higher to balance their budgets. And of these nations, it is thought that Iran is the most vulnerable to falling prices. A 2009 estimate put Iran’s break-even cost of its oil production at $90 per barrel.

It is likely that Iran is a target of the Saudis’ move to depress oil prices. If this is the case, one of the biggest impacts of Saudi Arabia’s decision to keep pumping oil may be the fracturing of opec. Divisions between the low-cost oil producing nations led by Saudi Arabia and the high-cost producing nations led by Iran will become increasingly stark.

Budget pressures in Iran, Libya and Algeria could soon lead to crisis situations. For a preview of what may await the people of these nations, just look at Venezuela, where social welfare spending is being slashed, inflation is destroying people’s savings, store shelves are empty, violent rioting is widespread, and revolution may be in the air.

Expect falling oil prices to also empower the radicals.

In Nigeria, for example, a weakened government will be less able to resist Muslim Boko Haram terrorists pushing toward its city centers. Expect more #BringBackOurGirls hashtags.

In Libya, watch for the civil war to heat up again as various terrorist groups fight to maintain their share of shrinking oil revenues. The southern portions of Libya especially will be a hotbed for extremists, potentially destabilizing neighboring countries.

Most importantly, watch Iran, the regional kingpin and world’s worst terrorist-sponsoring nation. Iran has one of the Middle East’s toughest armies, its biggest economy, and its second-largest population. It is also locked in a game of nuclear chicken with the U.S. and Europe. What will it do to cope with lower oil prices? Will Tehran stir up trouble in the Strait of Hormuz, the strategic choke point through which 30 percent of all seaborne oil passes? What will it do with Iraq’s oil fields, as it battles the Islamic State for influence in the country? Will Iran activate its agents within the local Shiite population in Bahrain, which is adjacent to Saudi Arabia’s most important oil fields? Or will it take some other radical action to boost oil prices?

Although Saudi Arabia seems to hold oil prices hostage for now, that could completely change if Iran blockaded the Persian Gulf or obtained nuclear weapons.

A desperate Iran will be a dangerous and unpredictable Iran. Don’t be surprised if it lashes out and reminds the world who the region’s supreme leader is.

The nations may not be worrying about low oil prices for long.

Russia: The Bigger Question

Perhaps the biggest question facing the world right now is, what will Russian President Vladimir Putin do?

The International Energy Agency estimates that oil and gas account for 68 percent of Russia’s exports and 50 percent of its federal budget.

Remember how the U.S. recently experienced government gridlock and shutdown over minuscule proposed cuts to spending? Imagine if the government had to immediately cut its budget by 25 to 30 percent to pay the bills—while seeing the value of the dollar evaporate by 60 percent over a matter of months. This is the situation facing Russia. And it comes as Russia’s economy is also being battered by the West’s economic sanctions.

So what will Putin do?

Some analysts, like the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman, have suggested that Saudi Arabia is working in conjunction with the U.S. to drive oil prices down in an effort to bankrupt both Iran and Russia. This is a theme that Putin has also highlighted. In an interview with Chinese media ahead of the November Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, Putin said this when asked about cheap oil: “[A] political component is always present in oil prices. … [D]erivatives greatly increasing the volatility of oil prices are being actively used. Unfortunately, such a situation creates the conditions for speculative activity and, as a consequence, for manipulating the prices in someone’s interests.”

On December 18, in his annual speech, Putin said Russia’s existence was on the line: “Sometimes I think, maybe it would be better for our bear to sit quiet, rather than chasing around the forest after piglets. To sit eating berries and honey instead. Maybe they will leave it in peace. They will not. Because they will always try to put him on a chain, and as soon as they succeed in doing so they tear out his fangs and his claws. … Once they’ve taken out his claws and his fangs, then the bear is no longer necessary. He’ll become a stuffed animal. The issue is not Crimea, the issue is that we are protecting our sovereignty and our right to exist.”

This does not sound like a man ready to concede defeat. It sounds more like a man preparing his nation for action.

The capacity of the Russian people to endure suffering is probably among the world’s greatest. The West grossly underestimates the determination and morale of the typical Russian (article, page 24).

So what will Putin do? What he is already doing: He will tighten his embrace of China.

On September 10, China’s state-run People’s Daily Online announced that China had agreed to help Russia construct one of the largest ports in Northeast Asia on Russia’s Sea of Japan coast. The seaport will be built to handle about 66 million tons of cargo a year, making it as big as Britain and France’s largest ports.

Then there were the two aforementioned massive pipeline construction deals Putin and China have agreed to. Once these pipelines are complete, Putin will be able to turn off the energy taps to Europe without losing access to customers and their bank accounts.

As dangerous as Europe’s energy dependence on Russia is, it will be many times worse in just a few years when those pipelines are finished. This scares Europe’s leaders. We could see influential Europeans push to repair relations with Russia. Remember, sanctions are a two-way street. And it is Europe, not America, that is bearing the brunt of the Russian sanction pain.

Russia will also continue its asymmetrical warfare against America. On December 20, China and Russia agreed to a $24 billion currency-swap program, which will help Russia mitigate the West’s sanctions.

Perhaps more threateningly, Russia has also announced the creation of a money-transfer system outside of the U.S.-controlled swift electronic payment system. This is an attack on the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

swift is the method by which banks transfer money and convert it to dollars for payment. Without access to this system, nations essentially have to revert to barter. In August, British Prime Minister David Cameron publicly asked for Russia to be kicked out of the system. Russian Deputy Finance Minister Alexey Moiseev promptly responded by saying Russia’s own alternative system would go live in May 2015 if Europe and America followed through. If China, the world’s number one exporting nation, could be convinced to use the Russian system, this could reduce demand for dollars.

The West’s sanctions, coupled with the falling oil price, is driving Russia and China together in a way that otherwise would probably have been impossible. Geopolitically, this is a game changer.

The last time the world had to deal with a Russia whose eastern flank was secure was the outbreak of World War ii.

A Russia with a secure eastern frontier makes Putin a very dangerous man.

America’s war on Russia may seem to be working today—but it is actually backfiring. Far from defanging Russia, it is more akin to poking it with a stick. Once the Ukrainian crisis blows over, Putin will be free to get far more involved in European relations.

Keep Your Eyes Open

2015 is off to an explosive start. And prophetically, it may be a world-changing year. Some of the most dramatic prophecies in the Bible appear to be coming to fruition at race-car velocities, accelerated by plunging oil prices. Longtime Trumpet readers will recognize them.

The “kings of the east” are cooperating in unprecedented fashion as oil prices and sanctions push Russia and China into each other’s arms. A desperate Russia, led by a dictatorial strongman (known in the Bible as the “prince of Rosh”), is frightening Europe. The “king of the north,” a prophesied European superpower composed of 10 nations or groups of nations, is coalescing around Germany for defense. The Bible says these kings will be led by a strongman (from Germany) who will lead Europe to world war once again.

Meanwhile, the Middle East is fracturing into its two prophesied power blocs. The first group is composed of Arab nations, including Saudi Arabia, that will ally with Germany. The second is the “king of the south,” which the Trumpet has identified as Iran leading the radical Islamic camp. Low oil prices are devastating Iran’s economy. Will Iran attempt something radical to drive oil prices back up—perhaps launch a nuclear weapon? High oil prices strike directly at the economies of Europe. Daniel 11:40 says the king of the south will “push” at the king of the north, who will respond like a whirlwind. How much will oil as a weapon play in this push?

(You can prove all of these prophecies by requesting free copies of our article “The Ukraine Crisis Was Prophesied” and our booklets Russia and China in Prophecy, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire and The King of the South.)

Low gas prices may give some people happy feelings, but beneath the surface is a world of cut-throat geopolitics in which nations are fighting for power and survival. Over the long term, supply and demand do drive price. But right now we are in a world in which oil production is a weapon of war—a tool to batter enemies into submission. Enjoy the $2-per-gallon gas while it lasts.