The Great Depression Remix

The 1929 financial crash was masterfully composed to inflict punishment. Every time stock investors thought it was safe to get back in the dance, they just lost more money. Every time consumers thought it was safe to start spending again, the job scene hit another low note. Businesses couldn’t hold a tune—they went bankrupt by the thousands.

Eight decades later, the question facing the world is this: Is the worst really over, or is it just the opening note of a very familiar hymn?

We are singing the same song. And even if the lyrics are not exactly the same, this verse certainly rhymes with the first. History repeats itself. Unfortunately, most people don’t know history.

Ask the average guy on the street. He is almost sure to tell you that he has heard on television or read on the Internet that the crisis is over.

The Wall Street Journal blares: “Economists Call for Bernanke to Stay, Say Recession Is Over” (August 11). Newsweek’s Daniel Gross confirms: “I’m prepared to declare that the recession is really, most probably over” (July 14). Bloomberg and Forbes are whistling their own happy tunes proclaiming the end of the recession too.

The good old times are back. Stocks will keep going up until 2010, says money manager John Dorfman. “On balance … I think the evidence favors continued gains.”

Sadly, it is all too familiar.

In 1930, the average person was singing that the worst was over too—as did many of the so-called professionals.

“The spring … marks the end of a period of grave concern …. American business is steadily coming back to a normal level of prosperity,” wrote Julius Barns, head of Hoover’s National Business Survey (March 16, 1930).

Actually, the worst was only beginning.

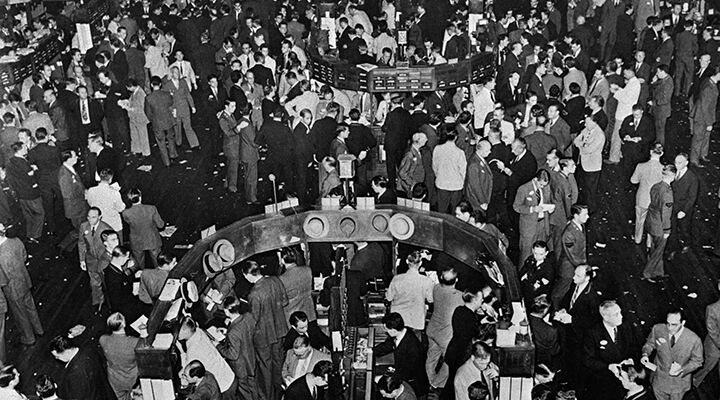

From 1921 to 1929, the Dow Jones hummed from 60 to a high note of almost 400! The Great Crash of 1929 changed that. It swallowed 48 percent of stock market value in just a few days! But over the ensuing months, the market bounced back, reclaiming around half of its losses. Investors breathed a collective sigh of relief and money managers loaded up the stocks again.

And then the stock market promptly crashed again, sending both share prices and bankers into funeral dirges.

Over the next three years, the market would “sucker rally” five times—only to plunge to new lows on each occasion. Yet with each new rally, the professionals invariably belted out that the crisis was over.

On Aug. 23, 1930, Moody’s Investors Service wrote regarding its prosperity index: “We are, therefore, inclined to regard the present level of business activity as the approximate level from which recovery will begin” (emphasis mine).

And the market plunged.

On Nov. 15, 1930, the Harvard Economic Review predicted: “We are now near the end of the declining phase of the Depression.”

And the market plunged again.

It would take more than three years of ups followed by dramatic downs before the Dow Jones would hit a real bottom—all the way back to around 50. If you were 55 years old when the market crashed in 1929, you would have probably died of old age before you got your money back, if at all.

For the general economy, it took a decade of hopeful high notes and octave-dropping lows and finally a literal worldwide bloodbath to end the Depression. The excesses of the Roaring Twenties would not be rectified over a few short, relatively painless months.

Here is the point. Whether you look at the stock market, world industrial output, or trade, the tune matches 1930. By some measures, things are even more discordant.

By March of this year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had crashed by 53 percent from its highs. The corresponding fall in 1929 was 48 percent. The Dow has now subsequently rallied by 46 percent—just as it did 79 years ago. Where to next?

The stock market’s lengthy slump has ended at last, says popular Goldman Sachs soothsayer Abby Joseph Cohen. “We do think that the new bull market has begun.”

“There is little evidence to be cautious,” composed Citigroup strategist Tobias Levkovich last week.

Can you hear the pickup note to the next stanza? And the market plunged again.

Yet the stock market is not the only indicator that is in hurtful harmony with 1930.

According to the most recent data presented by VoxEU.org, an economic policy research center, world industrial production is also in uneasy unison with the 1930s fall. A look at the charts reveals a déjà vu nightmare chorus. Both the United States and Canada have seen see their industrial production fall parallel to the 1929 crisis, as have Germany and Britain. Italy and France, however, are doing much worse. And, as of April, Japan’s output was 25 percent lower than during the equivalent stage in the Great Depression.

In the area of trade, the world is also worse off than our predecessors. Trade levels have fallen right off a cliff. Considering the prominence attached in historical literature to trade destruction compounding the effects of the Great Depression, this note should be especially alarming.

The main difference this time around is in debt levels. The willingness of authorities to borrow and spend money has blown out all records. The world is spending money like it is going out of style. America alone has spent more money combating the recession than it has on any other event in history, including World War ii.

All the money might buy a little time—it might make the faux recovery last a bit longer—but it doesn’t change anything. A problem caused by too much spending and debt cannot be fixed by more of the same.

Unfortunately, America looks like it is getting set up for a refrain. The excesses of the past two-plus decades have not been rectified during the past few short months. Money has been spent, but nothing fundamental has changed. More punishment is on the way.

History is repeating; you can feel the rhythm. The crescendo awaits.